Cerebellar Malformation: Deficits in early neural tube identity found in CHARGE syndrome

CHARGE syndrome is a genetic condition that involves multiple malformations in newly born children. The acronym stands for coloboma (a hole in the eye), heart defects, choanal atresia (a blockage of the nasal passage), retarded growth and development, genital abnormalities, and ear anomalies (Lalani et al., 2012). Now, in eLife, Albert Basson of King’s College London (KCL) and co-workers—including Tim Yu of KCL as first author—report that underdevelopment of a region of the cerebellum called the vermis is also associated with CHARGE syndrome (Yu et al., 2013).

Most cases of CHARGE syndrome can be related to a mutation in the gene that encodes CHD7, a protein that is involved in remodelling chromatin (Janssen et al., 2012). The latest work by Yu et al. shows that loss of CHD7 also disrupts the development of the early neural tube, which is the forerunner of the central nervous system. This results in underdevelopment (hypoplasia) of the cerebellar vermis. This finding is extremely exciting as it represents the very first example of this particular class of neural birth defect to be observed in humans.

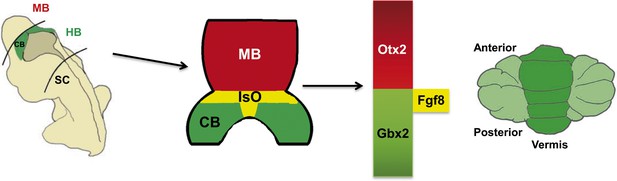

One of the first steps in the development of the central nervous system is the establishment of gene expression domains that segment the neural tube into the regions that become the forebrain, the midbrain, the hindbrain and the spinal cord. Subsequently, signalling centres establish the boundaries between these regions and secrete growth factors which pattern the adjacent nervous tissue (Kiecker and Lumsden, 2012). The best understood signalling centre is the Isthmic Organizer, which forms at the boundary of the midbrain and the hindbrain. This centre secretes fibroblast growth factor 8 (Fgf8) and other growth factors, and is essential for defining the regions of the neural plate that will become the posterior midbrain and the cerebellum (Figure 1).

The role of the Isthmic Organizer.

The establishment of gene expression domains along the anterior-posterior axis helps to segment the developing brain into the forebrain, midbrain (MB), hindbrain (HB) and spinal cord (SC). Signalling centres established at the boundaries between these segments secrete growth factors which pattern the adjacent nervous tissue. The Isthmic Organizer (IsO; shown in yellow) forms at the boundary of the posterior midbrain and anterior hindbrain: the IsO secretes Fgf8 and other growth factors, and is essential for defining the regions of the neural plate that will become the posterior midbrain (shown in blue) and the cerebellum (CB; green). The homeobox genes Otx2 and Gbx2 are involved in the formation of the IsO and in regulating the expression of Fgf8 by the IsO. Mutations in the CHARGE syndrome gene, CHD7, can alter Otx2, Gbx2 and Fgf8 expression, resulting in underdevelopment of a region of the cerebellum called the vermis (right).

Figure modified from Basson and Wingate, 2013

Extensive experiments in model vertebrates (such as mice, chickens and zebrafish) have shown that if the Isthmic Organizer fails to develop, there is dramatic and rapid cell death in adjacent regions of the neural tube. Mutant mice in which the Isthmic Organizer cannot express Fgf8 at all do not survive post-natally (Chi et al., 2003). However, reduced Fgf8 signalling or a failure to maintain Fgf8 expression does not result in animal death, but rather causes cerebellar vermis hypoplasia (Basson et al., 2008; Sato and Joyner, 2009). The genetic regulatory network that leads to the formation of the Isthmic Organizer is highly conserved across vertebrates, and beyond (Robertshaw and Kiecker, 2012), and it has long been postulated that disruption of the Isthmic Organizer must, therefore, be a cause of human cerebellar malformation. However, until now, this classical developmental phenotype had not been recognized in human patients.

With recent developments in neuroimaging, neuropathology and neurogenetics, many developmental disorders of the cerebellum, including cerebellar vermis hypoplasia, have emerged as causes of neurodevelopmental dysfunction (Doherty et al., 2013). Together, these disorders are relatively common, occurring roughly once in every 3000 live births. Cerebellar malformations can occur in isolation or as part of a broader malformation syndrome involving multiple systems. Although several cerebellar malformation genes have been identified, no gene directly involved in the formation or function of the Isthmic Organizer had previously been implicated in this class of birth defect, suggesting that Isthmic Organizer disorders might not be compatible with survival in humans.

Previously several clinical reports had noted cerebellar deficits in a few CHARGE syndrome patients. Now Yu, Basson and co-workers—who are based in London, Groningen and New York—report the results of MRI scans of a large cohort of 20 patients with CHARGE syndrome (caused by a mutation in CHD7; Yu et al., 2013). They confirm multiple cerebellar abnormalities in 55% of these patients, with 25% of the patients having cerebellar vermis hypoplasia.

Yu et al. also report the results of experiments of mice lacking one or both working copies of the Chd7 gene. Mice lacking one working copy of the gene did not have any obvious cerebellar phenotype, but cerebellar vermis hypoplasia was evident when one copy of the Fgf8 gene was also removed, suggesting genetic synergy between Chd7 and Fgf8. Expression of Fgf8 and its downstream gene Etv5 were significantly down regulated at the junction of the midbrain and the hindbrain during the early development of Chd7 mutant mice. Thus, reduced Fgf8 expression represents an underlying cause of CHARGE-related vermis hypoplasia because cerebellar development is exquisitely sensitive to the level of Fgf8 signalling.

Going one step further, Yu et al. next demonstrated that the expression of two genes that regulate Fgf8 expression at the Isthmic Organizer (Otx2 and Gbx2) is altered in mice lacking both working copies of the Chd7 gene. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays subsequently revealed that Chd7 is associated with enhancer elements belonging to the Otx2 and Gbx2 genes, which suggests that Chd7 has a direct role in regulating these essential Isthmic Organizer genes.

Together these results provide substantial evidence that cerebellar vermis hypoplasia in CHARGE syndrome is caused by dysfunction of the Isthmic Organizer in the early embryo. Further, the work of Basson, Yu and co-workers suggests that Isthmic Organizer disruption may be a more common cause of human cerebellar malformation than previously thought. Although complete loss-of-function mutations in genes that are central to the formation of the Isthmic Organizer (such as Otx2, Gbx2 and Fgf8) are still likely to be incompatible with human life, this study implies that genes which regulate the expression of central Isthmic Organizer genes may cause cerebellar malformation when mutated.

CHD7 is expressed in a wide variety of tissues during development, and CHARGE syndrome phenotypes indicate that it has tissue-specific and developmental stage-specific roles. A difficult question remains as to how CHD7 achieves different functions in different tissues. For example although loss of Chd7 disrupts Isthmic Organizer Fgf8 expression, Fgf8 expression is normal in the adjacent pharyngeal arches of the embryo. One possibility is that Cdh7 has different binding partners in different tissues.

Intriguingly, it has recently been shown that Cdh7 interacts with a small number of other transcription factors in neural stem cells, and that mutations in these other factors underlie a number of human malformation disorders (Engelen et al., 2011). One exciting prediction of this finding in combination with the work of Yu et al. on CHD7, is that systematic analysis of cerebellar morphology may uncover previously unrecognized cerebellar deficits related to Isthmic Organizer function in a wide range of other human birth defect syndromes.

References

-

Mutation update on the CHD7 gene involved in CHARGE syndromeHuman Mutation 33:1149–1160.https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.22086

-

The role of organizers in patterning the nervous systemAnnual Reviews of Neuroscience 35:347–367.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150543

-

Phylogenetic origins of brain organisersScientifica 2012:475017.https://doi.org/10.6064/2012/475017

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: December 24, 2013 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2013, Haldipur and Millen

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 659

- views

-

- 79

- downloads

-

- 4

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Developmental Biology

Inhibitory G alpha (GNAI or Gαi) proteins are critical for the polarized morphogenesis of sensory hair cells and for hearing. The extent and nature of their actual contributions remains unclear, however, as previous studies did not investigate all GNAI proteins and included non-physiological approaches. Pertussis toxin can downregulate functionally redundant GNAI1, GNAI2, GNAI3, and GNAO proteins, but may also induce unrelated defects. Here, we directly and systematically determine the role(s) of each individual GNAI protein in mouse auditory hair cells. GNAI2 and GNAI3 are similarly polarized at the hair cell apex with their binding partner G protein signaling modulator 2 (GPSM2), whereas GNAI1 and GNAO are not detected. In Gnai3 mutants, GNAI2 progressively fails to fully occupy the sub-cellular compartments where GNAI3 is missing. In contrast, GNAI3 can fully compensate for the loss of GNAI2 and is essential for hair bundle morphogenesis and auditory function. Simultaneous inactivation of Gnai2 and Gnai3 recapitulates for the first time two distinct types of defects only observed so far with pertussis toxin: (1) a delay or failure of the basal body to migrate off-center in prospective hair cells, and (2) a reversal in the orientation of some hair cell types. We conclude that GNAI proteins are critical for hair cells to break planar symmetry and to orient properly before GNAI2/3 regulate hair bundle morphogenesis with GPSM2.

-

- Computational and Systems Biology

- Developmental Biology

Organisms utilize gene regulatory networks (GRN) to make fate decisions, but the regulatory mechanisms of transcription factors (TF) in GRNs are exceedingly intricate. A longstanding question in this field is how these tangled interactions synergistically contribute to decision-making procedures. To comprehensively understand the role of regulatory logic in cell fate decisions, we constructed a logic-incorporated GRN model and examined its behavior under two distinct driving forces (noise-driven and signal-driven). Under the noise-driven mode, we distilled the relationship among fate bias, regulatory logic, and noise profile. Under the signal-driven mode, we bridged regulatory logic and progression-accuracy trade-off, and uncovered distinctive trajectories of reprogramming influenced by logic motifs. In differentiation, we characterized a special logic-dependent priming stage by the solution landscape. Finally, we applied our findings to decipher three biological instances: hematopoiesis, embryogenesis, and trans-differentiation. Orthogonal to the classical analysis of expression profile, we harnessed noise patterns to construct the GRN corresponding to fate transition. Our work presents a generalizable framework for top-down fate-decision studies and a practical approach to the taxonomy of cell fate decisions.