Mating Behaviour: To mate or not to mate

The theory of natural selection is often summarised with the phrase ‘the survival of the fittest’. But simply surviving is not enough; organisms must also reproduce, otherwise there would be no evolution. In the animal kingdom, for example, colourful feathers, sophisticated songs and elaborate courtship rituals are all employed to increase the chances of a successful copulation. Naturalists have marvelled at these mating rituals for hundreds of years and filled countless notebooks with descriptions and drawings of them. However, a more detailed understanding of mating behaviour has had to wait for arrival of new techniques in genetics and neuroscience, and the rise to fame of the vinegar fly, Drosophila melanogaster, as a model organism.

Vinegar flies (or common fruit flies) perform an elaborate courting ritual: first, a male orients towards and follows a female; then he touches her abdomen with his foreleg and, if she responds, he extends one of his wings and performs a song-like vibration with it. Finally he licks the female’s genitalia and attempts to copulate with her. Now, in eLife, Benjamin Kallman, Heesoo Kim and Kristin Scott of the University of California at Berkeley identify further pathways that guide mating decisions in male flies (Kallman et al., 2015).

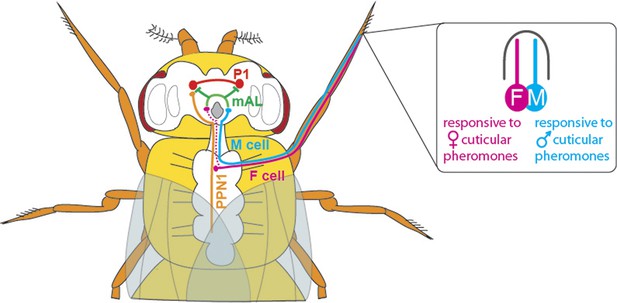

With the discovery of the transcription factor Fruitless (which is expressed only in males, and called FruM for short), we now know that around 1,500 neurons orchestrate courtship behaviour in these flies (Manoli et al., 2005; Stockinger et al., 2005). However, little is known about how these neurons are connected to achieve this behaviour. Previous studies have shown that chemicals present on the cuticle can affect courtship behaviour in flies (Yamamoto and Koganezawa, 2013). The cuticular pheromones produced by a female fly promote mating and allow the courting male to identify her as a female of the same species; the pheromones produced by males have the opposite effect and inhibit courtship. Flies detect these compounds via a pair of sensory neurons housed in their leg bristles. The neurons that respond to male pheromones are called M cells, and those that respond to female pheromones are called F cells (Figure 1; Pikielny, 2012; Thistle et al., 2012).

The neuronal circuitry underlying male-specific courtship behaviour in flies.

The leg bristles of flies contain neurons called F cells (shown in pink) that respond to female pheromones, and M cells (blue) that respond to male pheromones. Kallman et al. show that the F cells connect with PPN1 neurons (orange) in the ventral nerve cord; the PPN1 neurons then activate P1 neurons (red) in a part of the higher brain called the protocerebrum. The M cells project to the mAL neurons (green), which inhibit the P1 neurons. The F cells also indirectly activate the mAL neurons (represented by the dotted line).

Kallman et al. used genetic and behavioural tools to show that activating the F and M cells can modify male courtship behaviour. In a second step, they were able to identify the connection between the F and M cells in the leg and a cluster of neurons (called P1 neurons) that is found only in the brain of male flies. Neurobiologists have become increasingly interested in P1 neurons over the last decade, and have shown that activating them correlates with the start of courtship behaviour (Clowney et al., 2015; Kohatsu et al., 2011). However, until recently, the roads that lead to P1 were hardly known.

Kallman et al. then monitored activity in the P1 cluster when they activated either F cells or M cells in the forelegs of male flies. F cell activation was seen to excite the P1 cluster and resulted in enhanced courtship, whereas M cell activation did not excite the P1 cluster and may even have suppressed it. However, given that F cells terminate in the fly’s thorax, Kallman et al. found that another class of neurons, called PPN1, serves as the link between F cells and the P1 cluster in the higher brain (Figure 1).

To uncover the targets of the M cells, Kallman et al. looked at the neurons that express the FruM transcription factor and observed how their activity changed when M cells were stimulated. They found that the M cells activated a cluster of neurons called mAL (Figure 1); this cluster had previously been shown to send out inhibitory signals (Kimura et al., 2005). Inactivating the mAL neurons led to males courting each other. But how does mAL normally inhibit male-male courtship? In a final set of experiments, Kallman et al. showed that mAL neurons form connections with P1 neurons and inhibit their activity. Thus, while activating F cells led to an overall activation of P1, activating M cells resulted in an overall inhibition of P1. This suggests that the balance between excitation and inhibition determines this male-specific behaviour.

The work of Kallman, Kim and Scott represents a beautiful example of how sensory information can be processed by a very restricted number of neurons to generate highly complex forms of behaviour. The future will tell whether this is a general feature of sensory networks.

References

-

Genes and circuits of courtship behaviour in Drosophila malesNature Reviews Neuroscience 14:681–692.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3567

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: December 23, 2015 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2015, Campetella et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,569

- views

-

- 177

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Cell Biology

- Neuroscience

Alternative RNA splicing is an essential and dynamic process in neuronal differentiation and synapse maturation, and dysregulation of this process has been associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Recent studies have revealed the importance of RNA-binding proteins in the regulation of neuronal splicing programs. However, the molecular mechanisms involved in the control of these splicing regulators are still unclear. Here, we show that KIS, a kinase upregulated in the developmental brain, imposes a genome-wide alteration in exon usage during neuronal differentiation in mice. KIS contains a protein-recognition domain common to spliceosomal components and phosphorylates PTBP2, counteracting the role of this splicing factor in exon exclusion. At the molecular level, phosphorylation of unstructured domains within PTBP2 causes its dissociation from two co-regulators, Matrin3 and hnRNPM, and hinders the RNA-binding capability of the complex. Furthermore, KIS and PTBP2 display strong and opposing functional interactions in synaptic spine emergence and maturation. Taken together, our data uncover a post-translational control of splicing regulators that link transcriptional and alternative exon usage programs in neuronal development.

-

- Genetics and Genomics

- Neuroscience

Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals the extent to which marmosets carry genetically distinct cells from their siblings.