Holoenzymes: Refreshing memories

Although people complain about their memory when they cannot find their keys or recall the name of someone they have just met, the fact is that some memories can persist for a lifetime. What are the molecular mechanisms that our brains use to store such long-term memories, and how does this information remain so stable over time? Decades after an event, few of the molecules originally present will still be around, so the mechanism that stores a memory must allow newly synthesized molecules to be updated by molecules that already ‘contain’ the memory. Now, in eLife, Jay Groves, John Kuriyan and co-workers—including Margaret Stratton and Il-Hyung Lee of the University of California Berkeley as joint first authors—suggest a surprisingly simple view of how one of the leading candidates for memory storage—a complex called a CaMKII holoenzyme—might be updated (Stratton et al., 2014).

CaMKII holoenzymes contain 12 nearly identical molecules of an enzyme called CaM kinase II (CaMKII), arranged into two hexagonal rings, and they are found at the synapses that connect nerve cells with each other. CaMKII is activated when the arrival of a nerve impulse at the synapse causes an increase in the concentration of calcium ions within the cell. Previous work showed that CaMKII was strongly activated during a process called ‘long-term potentiation’ that is thought to underlie learning (Lee et al., 2009). This process—which is induced when two nerve cells are active at the same time—increases the strength of the synapse between the two nerve cells.

Once activated, each CaMKII subunit can phosphorylate neighbouring subunits in the holoenzyme in a process called autophosphorylation (Hanson et al., 1994). Of great interest is the fact that the autophosphorylation of a particular site—a threonine called T286—makes the enzyme persistently active, even after the calcium levels return to baseline (Miller and Kennedy, 1986). CaMKII can thus be considered as a ‘switch’ that remains ‘on’ until the enzyme becomes dephosphorylated by a phosphatase enzyme.

In the cytoplasm of the nerve cell, phosphatase activity is high and CaMKII becomes dephosphorylated within about a minute (Lee et al., 2009). However, during the induction of long-term potentiation, some activated CaMKII holoenzymes are relocated from the cytoplasm to a part of the synapse called the postsynaptic density. Within this structure, the rate of dephosphorylation of T286 is very low (Mullasseril et al., 2007). Moreover, should a T286 site become dephosphorylated, it is likely to be rapidly rephosphorylated by the autophosphorylation process described above. Thus, it is relatively easy to see how the ‘on’ state of CaMKII within the synapse could provide a persistent memory.

But that raises the issue of whether the turnover of these proteins might erase the memory encoded by such switches. If a CaMKII holoenzyme that had been activated was later destroyed when it became old, and was replaced with newly synthesized proteins, information might be lost. But what if turnover involved the replacement of a subunit rather than the removal of an entire holoenzyme? This scenario, first proposed by Marc Goldring and myself in an early computational model of CaMKII (Lisman and Goldring, 1988), has now been shown to be plausible by the work of Groves, Kuriyan and colleagues at UC Berkeley, the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Allosteros Therapeutics (Stratton et al., 2014).

Two groups of holoenzymes were labelled with fluorescent tags of different colours, and mixed to determine if subunits could be exchanged between different holoenzymes. Using optical techniques with high resolution, Stratton, Lee et al. could see single holoenzymes that contained both coloured tags—proof that subunits had indeed been swapped. So if this is the way that the production and degradation of these proteins are balanced in cells, the stability of information storage during protein turnover could occur as follows: when a phosphorylated subunit in an ‘on’ holoenzyme is replaced by an unphosphorylated subunit, this new subunit is autophosphorylated by the other subunits, restoring the holoenzyme to its full ‘on’ state (Figure 1).

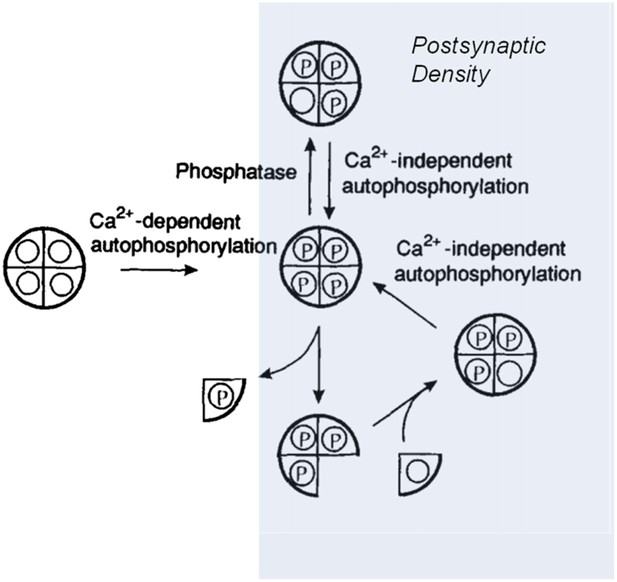

Model showing how the CaMKII switch remains ‘on’ despite protein turnover.

A CaMKII holoenzyme (left, shown here with only 4 of its 12 subunits) in the cytoplasm of a cell is generally unphosphorylated (denoted by the open circles), because the level of phosphatase activity is high. During the induction of long-term potentiation, the concentration of calcium ions (Ca2+) rises, leading to activation and autophosphorylation of CaMKII (denoted by the letter P). Some of these molecules relocate to the postsynaptic density (shaded area on right) where the phosphatase activity is very low; this means that autophosphorylation (see main text) can keep CaMKII fully phosphorylated. In the subunit exchange observed by Stratton, Lee et al., a phosphorylated subunit can be replaced by an unphosphorylated one, which is then autophosphorylated by its neighbouring subunits, returning the holoenzyme to its fully phosphorylated ‘on’ state.

Figure credit: Adapted from Lisman J, Goldring M. 1988. Evaluation of a model of long-term memory based on the properties of the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Journal de Physiologie 83:187–197

We are all attracted to simplicity and beauty in science, and the CaMKII switch described above has these qualities. Perhaps subunit exchange, followed by autophosphorylation between subunits, is as central to memory storage as the base pairing of DNA is to genetic memory. However, there are several other viable candidates for molecular memory (Kandel, 2012; Tsien, 2013). Moreover, although CaMKII has been strongly implicated in maintaining long-term potentiation (Sanhueza et al., 2011), its role in maintaining memory has not been tested by looking at behaviour in animals. The gold standard for such tests is to make a memory and then determine whether this memory can be erased by an attack on the candidate memory molecule. In the mid 2000s, there was considerable excitement when another enzyme, called PKM-zeta, appeared to pass this test, but it was later shown that knocking out the gene for PKM-zeta had little effect on long-term potentiation or memory (Volk et al., 2013). It will be exciting to see in years to come which of the candidate memory molecules can pass this gold standard test.

References

-

Feasibility of long-term storage of graded information by the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase molecules of the postsynaptic densityProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 85:5320–5324.https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.85.14.5320

-

Role of the CaMKII/NMDA receptor complex in the maintenance of synaptic strengthJournal of Neuroscience 31:9170–9178.https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1250-11.2011

-

Very long-term memories may be stored in the pattern of holes in the perineuronal netProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110:12456–12461.https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1310158110

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: January 29, 2014 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2014, Lisman

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 708

- Page views

-

- 77

- Downloads

-

- 5

- Citations

Article citation count generated by polling the highest count across the following sources: Crossref, Scopus, PubMed Central.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Biochemistry and Chemical Biology

- Plant Biology

Metabolism and biological functions of the nitrogen-rich compound guanidine have long been neglected. The discovery of four classes of guanidine-sensing riboswitches and two pathways for guanidine degradation in bacteria hint at widespread sources of unconjugated guanidine in nature. So far, only three enzymes from a narrow range of bacteria and fungi have been shown to produce guanidine, with the ethylene-forming enzyme (EFE) as the most prominent example. Here, we show that a related class of Fe2+- and 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases (2-ODD-C23) highly conserved among plants and algae catalyze the hydroxylation of homoarginine at the C6-position. Spontaneous decay of 6-hydroxyhomoarginine yields guanidine and 2-aminoadipate-6-semialdehyde. The latter can be reduced to pipecolate by pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase but more likely is oxidized to aminoadipate by aldehyde dehydrogenase ALDH7B in vivo. Arabidopsis has three 2-ODD-C23 isoforms, among which Din11 is unusual because it also accepted arginine as substrate, which was not the case for the other 2-ODD-C23 isoforms from Arabidopsis or other plants. In contrast to EFE, none of the three Arabidopsis enzymes produced ethylene. Guanidine contents were typically between 10 and 20 nmol*(g fresh weight)-1 in Arabidopsis but increased to 100 or 300 nmol*(g fresh weight)-1 after homoarginine feeding or treatment with Din11-inducing methyljasmonate, respectively. In 2-ODD-C23 triple mutants, the guanidine content was strongly reduced, whereas it increased in overexpression plants. We discuss the implications of the finding of widespread guanidine-producing enzymes in photosynthetic eukaryotes as a so far underestimated branch of the bio-geochemical nitrogen cycle and propose possible functions of natural guanidine production.

-

- Biochemistry and Chemical Biology

- Medicine

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is associated with higher fracture risk, despite normal or high bone mineral density. We reported that bone formation genes (SOST and RUNX2) and advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) were impaired in T2D. We investigated Wnt signaling regulation and its association with AGEs accumulation and bone strength in T2D from bone tissue of 15 T2D and 21 non-diabetic postmenopausal women undergoing hip arthroplasty. Bone histomorphometry revealed a trend of low mineralized volume in T2D (T2D 0.249% [0.156–0.366]) vs non-diabetic subjects 0.352% [0.269–0.454]; p=0.053, as well as reduced bone strength (T2D 21.60 MPa [13.46–30.10] vs non-diabetic subjects 76.24 MPa [26.81–132.9]; p=0.002). We also showed that gene expression of Wnt agonists LEF-1 (p=0.0136) and WNT10B (p=0.0302) were lower in T2D. Conversely, gene expression of WNT5A (p=0.0232), SOST (p<0.0001), and GSK3B (p=0.0456) were higher, while collagen (COL1A1) was lower in T2D (p=0.0482). AGEs content was associated with SOST and WNT5A (r=0.9231, p<0.0001; r=0.6751, p=0.0322), but inversely correlated with LEF-1 and COL1A1 (r=–0.7500, p=0.0255; r=–0.9762, p=0.0004). SOST was associated with glycemic control and disease duration (r=0.4846, p=0.0043; r=0.7107, p=0.00174), whereas WNT5A and GSK3B were only correlated with glycemic control (r=0.5589, p=0.0037; r=0.4901, p=0.0051). Finally, Young’s modulus was negatively correlated with SOST (r=−0.5675, p=0.0011), AXIN2 (r=−0.5523, p=0.0042), and SFRP5 (r=−0.4442, p=0.0437), while positively correlated with LEF-1 (r=0.4116, p=0.0295) and WNT10B (r=0.6697, p=0.0001). These findings suggest that Wnt signaling and AGEs could be the main determinants of bone fragility in T2D.