Prostate Cancer: SPOP the mutation

Changes to the genetic material of a cell can cause it to become cancerous. Recent data have demonstrated that extensive rearrangements of genetic material occur in prostate cancer (Berger et al., 2011; Baca et al., 2013). Generally, prostate tumors can be classified into those in which the rearrangement frequency is high or low. Now, in eLife, Mark Rubin of Weill Cornell Medical College and colleagues – including Gunther Boysen and Christopher Barbieri as joint first authors – shed light on why tumors with a mutation in a gene called SPOP have a high rearrangement frequency (Boysen et al., 2015).

Tumors with high rearrangement frequencies often have two genes deleted from their cells: the MAP3K7 gene, which is deleted in 30–40% of tumors; and the CHD1 gene, which is deleted in 15–20% of cancers (Liu et al., 2012). In prostate cancer, it is relatively rare to find mutations that affect single genes. However, recent large-scale genomic sequencing efforts have uncovered a few genes that are more often mutated than deleted or duplicated.

The most commonly mutated gene in prostate cancer encodes Speckle-type POZ protein (SPOP), which is mutated in around 10% of primary prostate tumors (Barbieri et al., 2012). In these tumors, mutations to the SPOP gene commonly occur alongside a loss of the CHD1 and MAP3K7 genes, and they are also associated with high numbers of genomic rearrangements. This has generally been attributed to the loss of the CHD1 protein. CHD4, a protein closely related to CHD1, directly interacts with DNA repair machinery (Pan et al., 2012), so it is widely assumed that CHD1 may also regulate DNA repair. However, there are currently no data to support this hypothesis.

Boysen, Barbieri et al. – who are based at Weill Cornell Medical College, the University of Trento and the Institute of Cancer Research in London – examined high-resolution genomic data from clinical prostate samples and found that SPOP mutations are strongly associated with high levels of genomic rearrangement. The CHD1 and MAP3K7 gene deletions were also equally and independently associated with large numbers of genomic rearrangements. However, an assessment of tumor clonality – the similarity of the genetic information found in different cells in the same tumor – suggested that the SPOP mutation occurred before the loss of either MAP3K7 or CHD1. This supports the hypothesis that the SPOP protein helps to initiate the development of prostate tumors.

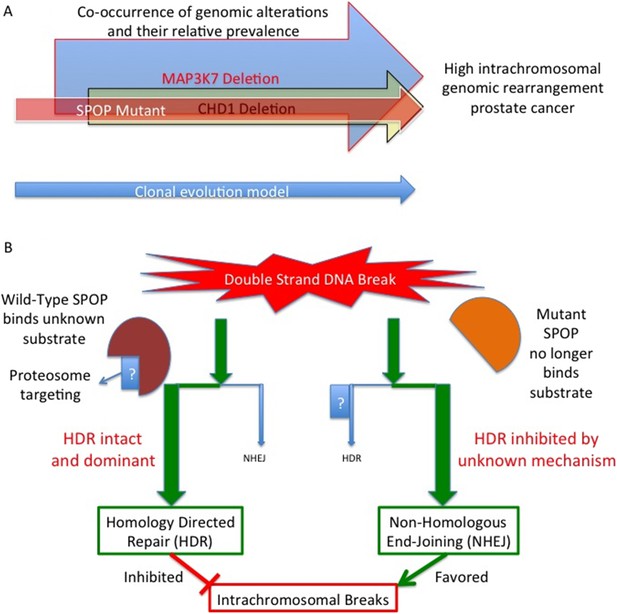

To uncover the molecular basis of this initiation, Boysen, Barbieri et al. used a zebrafish model to define how wild-type SPOP and a common SPOP mutant (called F133V) affect gene transcription. The data revealed that the presence of mutant SPOP causes an enrichment of genes that had previously been associated with mutant BRCA1 – a gene that is mutated in some breast and ovarian cancers. The identity of the affected genes suggested that SPOP affects DNA repair pathways. Further investigation in human and mouse models confirmed that mutant SPOP blocks a process called called homology–directed repair: this is the method that cells normally use to repair double-stranded DNA breaks. The cells then have to rely on a less reliable repair method (the non-homologous end-joining pathway), and this increases the number of genomic rearrangements (Figure 1).

Mutant SPOP promotes genomic rearrangements within chromosomes.

(A) SPOP mutation is an early event in a subtype of prostate cancer associated with a high genomic rearrangement frequency. The MAP3K7 and CHD1 proteins are also lost when SPOP mutations occur, and are each independently associated with high rearrangement frequencies. Based on a clonality model SPOP mutation preceeds MAP3K7 loss, which preceeds CHD1 loss. The frequency of loss for MAP3K7 (≅30%) is higher than that for CHD1 (≅15%) which is higher than the frequency with which SPOP mutation occurs (≅10%). (B) SPOP is an enzyme that enables homology-directed DNA repair (HDR) of double strand breaks. The substrate protein that is specifically involved in modulating repair is unknown. Mutant SPOP fails to promote HDR, and so the less stringent and more error prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway becomes the favored repair pathway. This results in a high degree of intrachromosomal breaks and hence more genomic rearrangements.

Previous work has demonstrated that drugs that inhibit PARP (poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1), such as olaparib, can kill BRCA1 mutant cancer cells, as well as other cells in which homology-directed repair does not work properly (Polyak and Garber, 2011). Boysen, Barbieri et al. therefore assessed whether SPOP mutant cells were also sensitive to olaparib, and found evidence that this is the case. This subtype of prostate cancer therefore has a unique sensitivity to PARP inhibition that could be immediately translated to clinical use.

Boysen, Barbieri et al. have provided key insight into how large numbers of genomic rearrangements occur in the aggressive SPOP/CHD1/MAP3K7 subtype of prostate cancer. However, additional studies are needed to establish further details about the specific pathways involved and to work out how the SPOP mutations interact with the loss of the CHD1 and MAP3K7 genes.

The SPOP protein targets various substrate proteins for degradation by adding a ubiquitin tag onto them. Known substrates of SPOP include the androgen receptor (An et al., 2014), the steroid co-activator SRC-3 (Geng et al., 2013), and the DEK and ERG oncogenes (Theurillat et al., 2014; An et al., 2015; Gan et al., 2015). All of these targets may affect the aggressiveness of prostate cancer. The specific target of SPOP in the context of DNA repair is not known and was not investigated by Boysen, Barbieri et al. However, all of these SPOP targets potentially interact with DNA repair processes, and there are many other identified SPOP targets with unknown roles that may produce the observed effects on the repair pathway. Future work will need to investigate this to provide more concrete mechanistic insight into the role of SPOP in modulating double-stranded DNA repair.

Loss of the CHD1 and MAP3K7 genes can also promote the development of prostate tumors in the absence of SPOP mutations (Wu et al., 2012; Rodrigues et al., 2015). In addition, they are both associated with enhanced genomic rearrangements when SPOP is intact, they are both highly clonal, and they both occur much more frequently than SPOP mutations. Modeling SPOP mutations in combination with CHD1 and MAP3K7 loss has not been reported; indeed, the specific roles of MAP3K7 and/or CHD1 loss in generating genomic rearrangements have not been explored. Given that CHD1 may affect DNA repair, and that the loss of the closely related CHD4 protein makes it easier for PARP inhibitors to kill cancer cells (Pan et al., 2012), such a model may provide mechanistic insights that focus future therapeutic approaches.

References

-

Prostate cancer-associated mutations in speckle-type POZ protein (SPOP) regulate steroid receptor coactivator 3 protein turnoverProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA 110:6997–7002.https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1304502110

-

Targeting the missing links for cancer therapyNature Medicine 17:283–284.https://doi.org/10.1038/nm0311-283

-

Suppression of Tak1 promotes prostate tumorigenesisCancer Research 72:2833–2843.https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2724

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: October 27, 2015 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2015, Rider and Cramer

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,899

- views

-

- 287

- downloads

-

- 5

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Cell Biology

Endogenous tags have become invaluable tools to visualize and study native proteins in live cells. However, generating human cell lines carrying endogenous tags is difficult due to the low efficiency of homology-directed repair. Recently, an engineered split mNeonGreen protein was used to generate a large-scale endogenous tag library in HEK293 cells. Using split mNeonGreen for large-scale endogenous tagging in human iPSCs would open the door to studying protein function in healthy cells and across differentiated cell types. We engineered an iPS cell line to express the large fragment of the split mNeonGreen protein (mNG21-10) and showed that it enables fast and efficient endogenous tagging of proteins with the short fragment (mNG211). We also demonstrate that neural network-based image restoration enables live imaging studies of highly dynamic cellular processes such as cytokinesis in iPSCs. This work represents the first step towards a genome-wide endogenous tag library in human stem cells.

-

- Biochemistry and Chemical Biology

- Cell Biology

Mediator of ERBB2-driven Cell Motility 1 (MEMO1) is an evolutionary conserved protein implicated in many biological processes; however, its primary molecular function remains unknown. Importantly, MEMO1 is overexpressed in many types of cancer and was shown to modulate breast cancer metastasis through altered cell motility. To better understand the function of MEMO1 in cancer cells, we analyzed genetic interactions of MEMO1 using gene essentiality data from 1028 cancer cell lines and found multiple iron-related genes exhibiting genetic relationships with MEMO1. We experimentally confirmed several interactions between MEMO1 and iron-related proteins in living cells, most notably, transferrin receptor 2 (TFR2), mitoferrin-2 (SLC25A28), and the global iron response regulator IRP1 (ACO1). These interactions indicate that cells with high MEMO1 expression levels are hypersensitive to the disruptions in iron distribution. Our data also indicate that MEMO1 is involved in ferroptosis and is linked to iron supply to mitochondria. We have found that purified MEMO1 binds iron with high affinity under redox conditions mimicking intracellular environment and solved MEMO1 structures in complex with iron and copper. Our work reveals that the iron coordination mode in MEMO1 is very similar to that of iron-containing extradiol dioxygenases, which also display a similar structural fold. We conclude that MEMO1 is an iron-binding protein that modulates iron homeostasis in cancer cells.