Plant Disease: Autophagy under attack

The Irish potato famine was responsible for more than one million deaths and the emigration of one million people from Europe in the 1840s (Andrivon, 1996). Today, the microbe that caused the famine, an oomycete called Phytophthora infestans, continues to cause serious outbreaks of disease in potato crops. Traditional control measures, such as fungicides and breeding for resistance, often have only marginal success in combating the disease, especially when the climate favors the growth and development of P. infestans (Fry and Goodwin, 1997). Now, in eLife, Sophien Kamoun, Tolga Bozkurt and colleagues – including Yasin Dagdas and Khaoula Belhaj as joint first authors – reveal how one of the proteins produced by P. infestans manipulates host plant cells to weaken their defenses (Dagdas et al., 2016).

It is well established that plant pathogens secrete proteins and small molecules – collectively known as effectors – that can interfere with plant defenses and make it easier for pathogens to infect and spread (Djamei et al., 2011; de Wit et al., 2009; Rovenich et al., 2014; Gawehns et al., 2014). However, as part of an ongoing arms race between plants and pathogens, some effectors are recognized by proteins in the host plant, which triggers immune responses that act to contain the infection. Relatively little is known about how effectors interfere with plant defenses. In particular, the identities of the plant molecules that are targeted by the effectors, and details of how the effectors are transported into plant cells, remain unclear.

The success of P. infestans as a pathogen is largely due to its ability to secrete hundreds of different effectors. Now, Dagdas, Belhaj et al. – who are based at the Sainsbury Laboratory, the John Innes Centre and Imperial College – report how they carried out a screen for plant molecules that interact with effectors from P. infestans (Dagdas et al., 2016). The experiments were carried out in the leaves of tobacco, which is a commonly used plant model, and show that an effector called PexRD54 targets a process called autophagy in plant cells.

Autophagy is a complex “self-eating” process that occurs when plant and other eukaryotic cells experience certain stresses – for example, due to a shortage of nutrients or a change in environmental conditions. During autophagy, cell material is broken down to supply the building blocks needed to maintain essential processes (Li and Vierstra, 2009). More recently, autophagy has been implicated in a variety of other situations, including restricting the growth and spread of invading microbes. A growing body of evidence suggests that autophagy plays a dual role both in promoting the survival of cells and in triggering cell death.

During autophagy, cell materials are sequestered by structures called autophagosomes and then delivered to acidic cell compartments where the material is degraded and recycled. In addition to supporting the bulk degradation of cell materials, it was recently shown that autophagy allows the selective removal of cellular components that are damaged or no longer needed. In selective autophagy, the sequestered material is loaded into autophagosomes by specific interactions between receptor proteins and specific autophagy proteins, such as the ATG8 proteins (Stolz et al., 2014, Lamb et al., 2013).

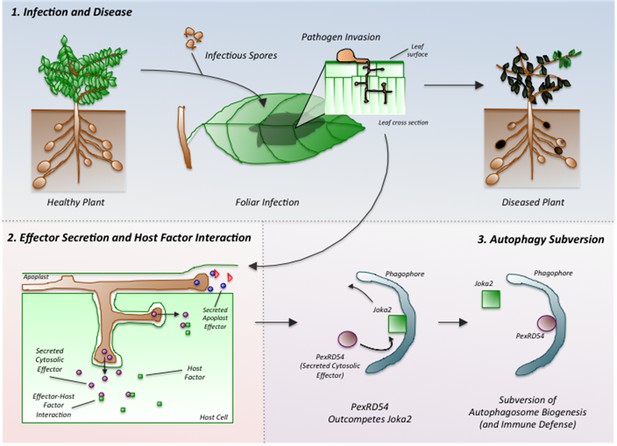

Dagdas, Belhaj et al. found that PexRD54 interferes with the activity of a potato cargo receptor called Joka2. PexRD54 out-competes Joka2 to bind to an ATG8 protein and stimulate the formation of an autophagosome in the plant cell (Figure 1). In doing so, the oomycete cleverly reduces the loading of specific types of cargo into autophagosomes and thus limits the plant defense response.

Phytophthora infestans interferes with the immune responses of potato plants.

Spores of P. infestans land on the leaves of potato plants and germinate (top middle). The growing fungus enters the leaves and spreads around the plant, leading to disease (top right). Proteins called effectors are released from the pathogen and some are taken into the cells of the host plant (bottom left). These effectors (purple ovals) interact with host factors (green squares) to promote the progression of the disease. Dagdas, Belhaj et al. found that a P. infestans effector called PexRD54 (purple oval; bottom right) out-competes a plant cargo receptor known as Joka2 (green square) on the surface of a membrane structure called a phagophore, which eventually becomes an autophagosome. In this way, PexRD54 prevents the loading of cargo proteins into autophagosomes and inhibits plant defenses.

The reported observations expand upon studies of mammalian pathogens that also harbor effectors that interfere with autophagy (Table 1). Taken together, this work provides a template for future investigations into the ways in which effectors subvert host plant defenses. However, a number of interesting questions remain unanswered. For example, how do cargo receptors work? How are they regulated? What is the nature of the cargo in the autophagosomes and how does it regulate immune responses? In addition, our understanding of the mechanisms that control selective autophagy remain incomplete. How is the selectivity regulated, and what other cell mechanisms might be subverted by effectors? Phytophthora diseases can have devastating effects, but as this study illustrates, they can also illuminate and advance our understanding of fundamental cellular processes.

Mammalian pathogens that express proteins that interfere with host autophagosome biogenesis or function.

| Domain | Pathogen | Host | Effector | Activity | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus | HIV virus | human | Nef1 | Inhibits host autophagy | Campbell et al., 2015 |

| CMV virus | human | Trs1 | Inhibits host autophagy | Chaumorcel et al., 2012 | |

| Dengue virus | mammal | NS4A | Upregulation of autophagy | McLean et al., 2011 | |

| Bacteria | Legionella | mammal | RavZ | Cleaves an Atg8 protein from pre-autophagosomes | Choy et al., 2012; Horenkamp et al., 2015 |

| Coxiella | mammal | Cig2 | Disrupts interactions between acidic compartments and host autophagosomes | Newton et al., 2014 | |

| Salmonella | mammal | SseL | Inhibits selective autophagy of cytosolic aggregates | Mesquita et al., 2012 | |

| Anaplasma phagocytophilum | mammal | Ats-1 | Hijacks a pathway that activates autophagy to promote its growth inside cells | Niu et al., 2012 | |

| Vibrio parahemolyticus | mammal | VopQ | Creates pores in acidic compartments in host cells | Sreelatha et al., 2013 | |

| Eukaryote | Phytophthora | plant | PexRD54 | Inappropriately activates the formation of autophagosomes | Dagdas et al., 2016 |

References

-

The human cytomegalovirus protein TRS1 inhibits autophagy via its interaction with beclin 1Journal of Virology 86:2571–2584.https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.05746-11

-

Fungal effector proteins: past, present and futureMolecular Plant Pathology 10:735–747.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1364-3703.2009.00591.x

-

The Fusarium oxysporum effector Six6 contributes to virulence and suppresses i-2-mediated cell deathMolecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 27:336–348.https://doi.org/10.1094/MPMI-11-13-0330-R

-

The autophagosome: origins unknown, biogenesis complexNature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 14:759–774.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm3696

-

Autophagy: a multifaceted intracellular system for bulk and selective recyclingTrends in Plant Science 17:526–537.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2012.05.006

-

Flavivirus NS4A-induced autophagy protects cells against death and enhances virus replicationJournal of Biological Chemistry 286:22147–22159.https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M110.192500

-

Autophagosomes induced by a bacterial beclin 1 binding protein facilitate obligatory intracellular infectionProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109:20800–20807.https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1218674109

-

Filamentous pathogen effector functions: of pathogens, hosts and microbiomesCurrent Opinion in Plant Biology 20:96–103.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2014.05.001

-

Late blight of potato and tomatoThe Plant Health Instructor.https://doi.org/10.1094/PHI-I-2000-0724-01

-

Cargo recognition and trafficking in selective autophagyNature Cell Biology 16:495–501.https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb2979

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: February 23, 2016 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2016, de Figueiredo et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 2,704

- views

-

- 480

- downloads

-

- 3

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Microbiology and Infectious Disease

- Structural Biology and Molecular Biophysics

African trypanosomes replicate within infected mammals where they are exposed to the complement system. This system centres around complement C3, which is present in a soluble form in serum but becomes covalently deposited onto the surfaces of pathogens after proteolytic cleavage to C3b. Membrane-associated C3b triggers different complement-mediated effectors which promote pathogen clearance. To counter complement-mediated clearance, African trypanosomes have a cell surface receptor, ISG65, which binds to C3b and which decreases the rate of trypanosome clearance in an infection model. However, the mechanism by which ISG65 reduces C3b function has not been determined. We reveal through cryogenic electron microscopy that ISG65 has two distinct binding sites for C3b, only one of which is available in C3 and C3d. We show that ISG65 does not block the formation of C3b or the function of the C3 convertase which catalyses the surface deposition of C3b. However, we show that ISG65 forms a specific conjugate with C3b, perhaps acting as a decoy. ISG65 also occludes the binding sites for complement receptors 2 and 3, which may disrupt recruitment of immune cells, including B cells, phagocytes, and granulocytes. This suggests that ISG65 protects trypanosomes by combining multiple approaches to dampen the complement cascade.

-

- Medicine

- Microbiology and Infectious Disease

Background:

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients experience immune compromise characterized by complex alterations of both innate and adaptive immunity, and results in higher susceptibility to infection and lower response to vaccination. This immune compromise, coupled with greater risk of exposure to infectious disease at hemodialysis (HD) centers, underscores the need for examination of the immune response to the COVID-19 mRNA-based vaccines.

Methods:

The immune response to the COVID-19 BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine was assessed in 20 HD patients and cohort-matched controls. RNA sequencing of peripheral blood mononuclear cells was performed longitudinally before and after each vaccination dose for a total of six time points per subject. Anti-spike antibody levels were quantified prior to the first vaccination dose (V1D0) and 7 d after the second dose (V2D7) using anti-spike IgG titers and antibody neutralization assays. Anti-spike IgG titers were additionally quantified 6 mo after initial vaccination. Clinical history and lab values in HD patients were obtained to identify predictors of vaccination response.

Results:

Transcriptomic analyses demonstrated differing time courses of immune responses, with prolonged myeloid cell activity in HD at 1 wk after the first vaccination dose. HD also demonstrated decreased metabolic activity and decreased antigen presentation compared to controls after the second vaccination dose. Anti-spike IgG titers and neutralizing function were substantially elevated in both controls and HD at V2D7, with a small but significant reduction in titers in HD groups (p<0.05). Anti-spike IgG remained elevated above baseline at 6 mo in both subject groups. Anti-spike IgG titers at V2D7 were highly predictive of 6-month titer levels. Transcriptomic biomarkers after the second vaccination dose and clinical biomarkers including ferritin levels were found to be predictive of antibody development.

Conclusions:

Overall, we demonstrate differing time courses of immune responses to the BTN162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in maintenance HD subjects comparable to healthy controls and identify transcriptomic and clinical predictors of anti-spike IgG titers in HD. Analyzing vaccination as an in vivo perturbation, our results warrant further characterization of the immune dysregulation of ESRD.

Funding:

F30HD102093, F30HL151182, T32HL144909, R01HL138628. This research has been funded by the University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Clinical and Translational Science (CCTS) award UL1TR002003.