Mitochondria: Selective protein degradation ensures cellular longevity

Mitochondria provide cells with energy and metabolite molecules that are essential for cell growth, and faulty mitochondria cause a number of severe genetic and age-related diseases, including Friedreich's ataxia, diabetes and cancer (Held and Houtkooper, 2015; Suliman and Piantadosi, 2016). To maintain mitochondria in a fully working state, cells have evolved a range of quality control systems for them (Held and Houtkooper, 2015). For example, faulty mitochondria can be removed through a process called mitophagy. In this process, which is similar to autophagy (the process used by cells to degrade unwanted proteins and organelles), the entire mitochondrion is enclosed by a double membrane. In yeast cells this structure fuses with a compartment called the vacuole, where various enzymes degrade and destroy the mitochondrion (Youle and Narendra, 2011). In animal cells an organelle called the lysosome takes the place of the vacuole.

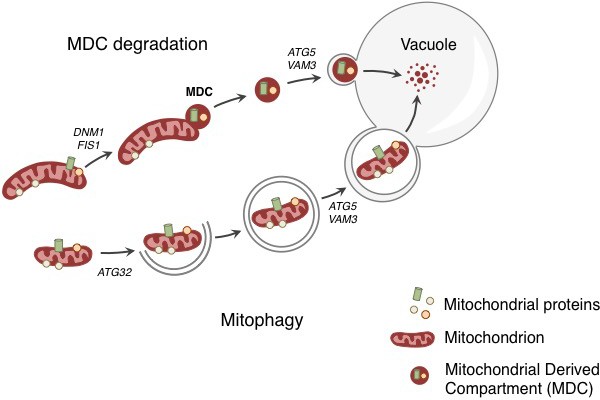

Now, in eLife, Adam Hughes, Daniel Gottschling and colleagues at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and University of Utah School of Medicine report evidence for a new quality control mechanism that helps to protect mitochondria from age- and stress-related damage in yeast (Hughes et al., 2016). In this mechanism, a mitochondrion can selectively remove part of its membrane to send the proteins embedded in this region to the lysosome/vacuole to be destroyed, while leaving the remainder of the mitochondrion intact (Figure 1).

Degradation of mitochondria and selected mitochondrial membrane proteins.

Yeast cells respond to stress and aging by sending a specific set of mitochondrial membrane proteins into the vacuole for degradation (top). This pathway involves the formation of a mitochondrial derived compartment (MDC), a process that is regulated by genes that are required for mitochondrial fission (DNM1 and FIS1). The fusion of the MDC to the vacuole depends on genes that are involved in the late stages of autophagy and mitophagy (ATG5 and VAM3). The MDC degradation pathway is distinct from the process of mitophagy (bottom), which involves the whole mitochondrion being enclosed in a membrane (grey lines) as a result of the activity of a gene called ATG32. The membrane-enclosed mitochondrion is then transported to the vacuole, where it is degraded.

Hughes et al. tracked the fate of Tom70, a protein that is found in the outer membrane of mitochondria, and discovered that it accumulated in the vacuole as the yeast aged. This accumulation was not the result of mitophagy, as Tom70 was directed to the vacuole even when a gene required for mitophagy was absent. Previous reports have linked cellular aging to a decline in mitochondrial activity (McMurray and Gottschling, 2003), which is caused by an earlier loss of pH control in the vacuole (Hughes and Gottschling, 2012). For this reason, Hughes et al. tested whether a drug that disrupts the pH of the vacuole triggers the degradation of Tom70. This appears to be the case – the drug caused Tom70 to move from the mitochondria to the vacuole for degradation.

Before Tom70 ended up in the vacuole it accumulated in a mitochondrial-derived compartment (MDC) at the surface of the mitochondria, close to the membrane of the vacuole. The formation of this compartment depended on the machinery that drives the process by which mitochondria divide. However, the subsequent delivery of the contents of the MDC to the vacuole used factors that are required for the late stages of autophagy (Figure 1).

Hughes et al. found that the MDC contained Tom70 and 25 other proteins, all of which are mitochondrial membrane proteins that rely on Tom70 to import them into the mitochondrial membrane. This suggests that the MDC degradation pathway selectively removes a specific group of mitochondrial proteins. An obvious question, therefore, is: how and why does disrupting the ability of the vacuole to control its pH trigger the selective delivery and degradation of these proteins?

Hughes et al. hypothesize that MDC formation is linked to metabolite imbalance, as the loss of acidity inside the vacuole prevents amino acids from being stored there (Klionsky et al., 1990). This in turn leads to a build up of amino acids in the cytoplasm that can overburden the transport proteins that import them into the mitochondria (Hughes and Gottschling, 2012). In this scenario, the selective degradation of mitochondrial transport proteins by the MDC pathway can be seen as a response that protects the organelle against an unregulated, and potentially harmful, influx of amino acids.

While MDCs still formed in very old yeast cells, they remained in vesicle-like structures in the cytoplasm and were not delivered to the vacuole. It therefore appears possible that the accumulation of undegradable cytosolic MDCs in the cytoplasm can contribute to the decline of the aging cell, much like the accumulation of protein aggregates does (Nystrom and Liu, 2014; Hill et al., 2014).

The discovery of MDCs and their role in delivering specific mitochondrial proteins to the vacuole for degradation raises a number of questions that may shed further light on both this process and the trials of aging. Do the MDCs contain regulatory factors that are required for delivering proteins into the vacuole? Why do MDCs fail to be delivered into the vacuole in old cells? The degradative enzymes inside the vacuole do not work well under conditions of elevated pH. It will therefore also be important to learn how long the degradation of mitochondrial membrane proteins can be maintained under these conditions (Kane, 2006).

References

-

The where, when, and how of organelle acidification by the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPaseMicrobiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 70:177–191.https://doi.org/10.1128/MMBR.70.1.177-191.2006

-

The fungal vacuole: composition, function, and biogenesisMicrobiological Reviews 54:266–292.

-

Protein quality control in time and space – links to cellular agingFEMS Yeast Research 14:40–48.https://doi.org/10.1111/1567-1364.12095

-

Mitochondrial quality control as a therapeutic targetPharmacological Reviews 68:20–48.https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.115.011502

-

Mechanisms of mitophagyNature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 12:9–14.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm3028

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: June 1, 2016 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2016, Malmgren Hill et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 2,650

- views

-

- 448

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Cell Biology

- Neuroscience

Alternative RNA splicing is an essential and dynamic process in neuronal differentiation and synapse maturation, and dysregulation of this process has been associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Recent studies have revealed the importance of RNA-binding proteins in the regulation of neuronal splicing programs. However, the molecular mechanisms involved in the control of these splicing regulators are still unclear. Here, we show that KIS, a kinase upregulated in the developmental brain, imposes a genome-wide alteration in exon usage during neuronal differentiation in mice. KIS contains a protein-recognition domain common to spliceosomal components and phosphorylates PTBP2, counteracting the role of this splicing factor in exon exclusion. At the molecular level, phosphorylation of unstructured domains within PTBP2 causes its dissociation from two co-regulators, Matrin3 and hnRNPM, and hinders the RNA-binding capability of the complex. Furthermore, KIS and PTBP2 display strong and opposing functional interactions in synaptic spine emergence and maturation. Taken together, our data uncover a post-translational control of splicing regulators that link transcriptional and alternative exon usage programs in neuronal development.

-

- Cell Biology

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neuromuscular disorder characterized by progressive weakness of almost all skeletal muscles, whereas extraocular muscles (EOMs) are comparatively spared. While hindlimb and diaphragm muscles of end-stage SOD1G93A (G93A) mice (a familial ALS mouse model) exhibit severe denervation and depletion of Pax7+satellite cells (SCs), we found that the pool of SCs and the integrity of neuromuscular junctions (NMJs) are maintained in EOMs. In cell sorting profiles, SCs derived from hindlimb and diaphragm muscles of G93A mice exhibit denervation-related activation, whereas SCs from EOMs of G93A mice display spontaneous (non-denervation-related) activation, similar to SCs from wild-type mice. Specifically, cultured EOM SCs contain more abundant transcripts of axon guidance molecules, including Cxcl12, along with more sustainable renewability than the diaphragm and hindlimb counterparts under differentiation pressure. In neuromuscular co-culture assays, AAV-delivery of Cxcl12 to G93A-hindlimb SC-derived myotubes enhances motor neuron axon extension and innervation, recapitulating the innervation capacity of EOM SC-derived myotubes. G93A mice fed with sodium butyrate (NaBu) supplementation exhibited less NMJ loss in hindlimb and diaphragm muscles. Additionally, SCs derived from G93A hindlimb and diaphragm muscles displayed elevated expression of Cxcl12 and improved renewability following NaBu treatment in vitro. Thus, the NaBu-induced transcriptomic changes resembling the patterns of EOM SCs may contribute to the beneficial effects observed in G93A mice. More broadly, the distinct transcriptomic profile of EOM SCs may offer novel therapeutic targets to slow progressive neuromuscular functional decay in ALS and provide possible ‘response biomarkers’ in pre-clinical and clinical studies.