Sensorimotor Transformation: The hand that ‘sees’ to grasp

How does the hand know what the eyes see? When we reach to grasp an object, our hand shapes to match the object's size, shape, and orientation. How does the brain translate visual information into motor commands that control the hand?

Now, in eLife, thanks to the work of Stefan Schaffelhofer and Hansjörg Scherberger of the German Primate Center in Göttingen, our understanding of this fundamental process has been significantly advanced (Schaffelhofer and Scherberger, 2016). We can think about the information that is represented in the activity of cells as a ‘code’. For the first time, cells that code for the visual properties of objects are distinguished from those that code for how the hand is moved to grasp.

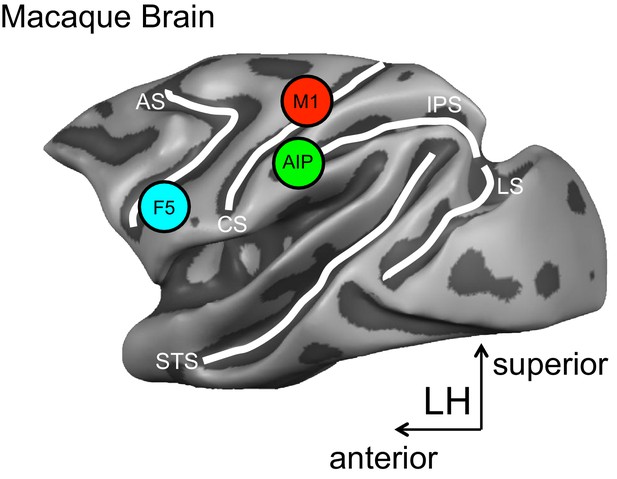

The approach used by Schaffelhofer and Scherberger records the hand movements and the activity of brain cells in monkeys while they view and grasp objects of different shapes and sizes. Recordings are taken from three brain areas known to be important for grasping – the anterior intraparietal (AIP) area, the ventral premotor area F5 and the primary motor hand area M1 (Figure 1).

A schematic representation of the brain areas implicated in the transformation of visual-to-motor information during grasping.

The cortical surface of the macaque monkey is shown. The cortical surface is defined at the gray-white matter boundary and has been partially inflated to reveal regions within the sulci (the grooves on the brain’s surface) while preserving a sense of curvature. AIP = anterior intraparietal area, F5 = ventral premotor area, M1 = primary motor hand area. White lines indicate sulci. IPS = intraparietal sulcus, STS = superior temporal sulcus, CS = central sulcus, AS = arcuate sulcus, LS = lunate sulcus. LH = left hemisphere. The monkey MRI data on which the reconstruction is based was provided by Stefan Everling.

The set of objects used in the study elicits a wide range of different hand postures. Critically, some objects look different but are grasped similarly, while others look identical but are grasped in different ways. This approach allows for cells that represent visual object properties (visual-object encoding) to be distinguished from those that represent how the hand is moved during grasping (motor-grasp encoding).

The results reveal predominately visual-object encoding in area AIP and motor-grasp encoding in areas F5 and M1. The cells in area AIP respond strongly during object viewing, and these responses clearly reflect object shape. Conversely, area F5 responds only weakly during the viewing period, and its activity strongly reflects hand movements during grasping.

It is particularly informative that when the objects are visually distinct but are grasped similarly, each object initially causes a distinct response in area AIP during the viewing period. These responses become more similar over time and before the start of a movement. This is consistent with a change from a visual-object to a motor-grasp encoding scheme. Area AIP also responds differently to visually identical objects that are grasped differently, which is also consistent with a motor-grasp encoding scheme.

Despite these aspects of their results, Schaffelhofer (who is also at Rockefeller University) and Scherberger (who is also at the University of Göttingen) maintain that altogether their data more strongly support a visual-object encoding account of AIP activity. They suggest that area AIP represents the visual features of objects that are relevant for grasping.

According to this account, over time AIP activity reflects a narrowing of action possibilities, honing in on the object features that will be essential for the upcoming grasp. This explains why responses to different objects that are grasped similarly become increasingly similar during planning, and why grasping the same object in different ways elicits distinct responses.

The findings also reveal that areas AIP and F5 briefly show common encoding when viewing objects, suggesting that these areas share information during this time. Speculatively, feedback from F5 may help to narrow the range of possible hand actions (specified visually in area AIP) to a single set of grasp points on the target object.

The results of Schaffelhofer and Scherberger also provide compelling evidence for the role of area F5 in driving the activity of the primary motor area M1. Response encoding during grasping becomes remarkably similar between areas F5 and M1, and F5 responses show earlier onsets. These data complement and extend previous results (Umilta et al., 2007; Spinks et al., 2008).

Altogether the new findings suggest the following model. Area AIP represents visual information about the features of objects. Together with area F5, area AIP then ‘flags’ those features that are most relevant for the intended actions, and the two areas collaborate to transform this information into the sensory and motor parameters that control the hand during grasping. Finally, area F5 signals this information to area M1, and ultimately the information reaches the spinal cord for controlling the hand and finger muscles.

This model can now be further tested. For example, the model predicts that area AIP will respond robustly and variably to objects that can be grasped in many different ways. The model also suggests that the more difficult it is to visually identify the parts of an object that will permit a stable grasp, the more rigorously AIP will respond.

It would also be interesting to see how the interplay between areas AIP and F5 unfolds when grasping the same object for different purposes (Marteniuk et al., 1987; Ansuini et al., 2006). Does the activity in area AIP first represent all the visual features of the object, as the current results of Schaffelhofer and Scherberger suggest? Or are the responses in area AIP adjusted to reflect those features of the object that are most relevant to the specific action that is intended?

References

-

Effects of end-goal on hand shapingJournal of Neurophysiology 95:2456–2465.https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.01107.2005

-

Constraints on human arm movement trajectoriesCanadian Journal of Psychology/Revue Canadienne De Psychologie 41:365–378.https://doi.org/10.1037/h0084157

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: July 29, 2016 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2016, Valyear

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,502

- views

-

- 101

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Neuroscience

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a prevalent sleep-related breathing disorder that results in multiple bouts of intermittent hypoxia. OSA has many neurological and systemic comorbidities, including dysphagia, or disordered swallow, and discoordination with breathing. However, the mechanism in which chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH) causes dysphagia is unknown. Recently, we showed the postinspiratory complex (PiCo) acts as an interface between the swallow pattern generator (SPG) and the inspiratory rhythm generator, the preBötzinger complex, to regulate proper swallow-breathing coordination (Huff et al., 2023). PiCo is characterized by interneurons co-expressing transporters for glutamate (Vglut2) and acetylcholine (ChAT). Here we show that optogenetic stimulation of ChATcre:Ai32, Vglut2cre:Ai32, and ChATcre:Vglut2FlpO:ChR2 mice exposed to CIH does not alter swallow-breathing coordination, but unexpectedly disrupts swallow behavior via triggering variable swallow motor patterns. This suggests that glutamatergic–cholinergic neurons in PiCo are not only critical for the regulation of swallow-breathing coordination, but also play an important role in the modulation of swallow motor patterning. Our study also suggests that swallow disruption, as seen in OSA, involves central nervous mechanisms interfering with swallow motor patterning and laryngeal activation. These findings are crucial for understanding the mechanisms underlying dysphagia, both in OSA and other breathing and neurological disorders.

-

- Neuroscience

The central tendency bias, or contraction bias, is a phenomenon where the judgment of the magnitude of items held in working memory appears to be biased toward the average of past observations. It is assumed to be an optimal strategy by the brain and commonly thought of as an expression of the brain’s ability to learn the statistical structure of sensory input. On the other hand, recency biases such as serial dependence are also commonly observed and are thought to reflect the content of working memory. Recent results from an auditory delayed comparison task in rats suggest that both biases may be more related than previously thought: when the posterior parietal cortex (PPC) was silenced, both short-term and contraction biases were reduced. By proposing a model of the circuit that may be involved in generating the behavior, we show that a volatile working memory content susceptible to shifting to the past sensory experience – producing short-term sensory history biases – naturally leads to contraction bias. The errors, occurring at the level of individual trials, are sampled from the full distribution of the stimuli and are not due to a gradual shift of the memory toward the sensory distribution’s mean. Our results are consistent with a broad set of behavioral findings and provide predictions of performance across different stimulus distributions and timings, delay intervals, as well as neuronal dynamics in putative working memory areas. Finally, we validate our model by performing a set of human psychophysics experiments of an auditory parametric working memory task.