Social Evolution: How ants send signals in saliva

Ant colonies are complex systems in which each ant fulfills a specific role to help the whole colony survive. The ants in a colony develop into distinct types known as castes to perform these roles. In colonies of leaf cutter ants, for example, small “worker” ants usually care for the larvae and the fungus the colony feeds on, while larger worker ants leave the nest to forage for new leaves to grow the fungus on. Other species, such as the silver ant, possess a soldier caste that has huge mouthparts dedicated to fighting. Finally, most colonies have one or several “queen” ants that focus on reproduction. It is important that the colony has the right numbers of each caste: if too many ants develop into soldiers, for example, the colony will starve, while a colony with too many foragers cannot take care of its larvae.

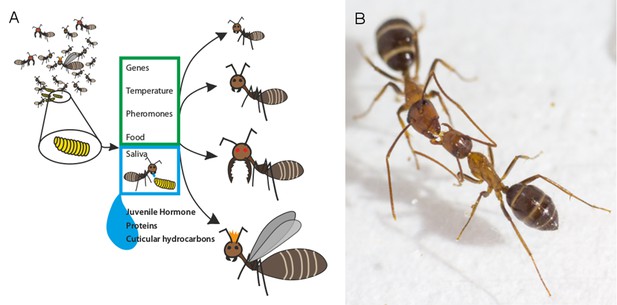

Genetic cues, environmental cues like food or the size of the colony, or a combination of both, can determine the caste that an individual will become (for a review see Schwander et al., 2010). Adult ants are able to influence the caste fate of larvae by changing the types of food they provide, by producing chemicals known as pheromones, and by regulating the temperature of the chamber the larvae live in (Wheeler, 1991). Now, in eLife, Laurent Keller and Richard Benton of the University of Lausanne and colleagues – including Adria LeBoeuf as first author – report on a new way in which adult ants can alter how larvae develop (LeBoeuf et al., 2016).

Juvenile hormone regulates development and reproduction in insects and also appears to affect caste fate in ants (Wheeler, 1986; Wheeler and Nijhout, 1981; Rajakumar et al., 2012; Nijhout, 1994). When the larvae of an ant called Pheidole bicarinata were exposed to increased amounts of a molecule that is very similar to juvenile hormone, most of them became soldiers instead of workers (Wheeler and Nijhout, 1981). However, it was not clear how the levels of this hormone were regulated in larvae.

Like most other social insects, adult ants feed their larvae by transferring fluid (saliva) mouth-to-mouth in a process called trophallaxis. LeBoeuf et al. – who are based at institutes in Switzerland, the US, Brazil, Japan and the UK – used mass spectroscopy and RNA sequencing to identify the molecules present in the saliva of the Florida carpenter ant (Camponotus floridanus). They found that, in addition to nutrients, ant saliva also contains juvenile hormone and other molecules including proteins, microRNAs and cuticular hydrocarbons (Figure 1). Furthermore, the amount of juvenile hormone transferred by trophallaxis is high enough to affect how the larvae develop.

Several factors influence the roles of individual ants in ant colonies.

(A) As a larva (yellow) prepares to transform into an adult ant, a number of factors determine whether it will develop into, for example, a nurse, a forager, a soldier or a queen (right: top-to-bottom). Previous studies have shown that genetic factors and environmental cues can influence this outcome (green box). LeBoeuf et al. show that when adult ants feed larvae mouth-to-mouth (blue box), a variety of signal molecules are transferred alongside the nutrients in the saliva of the adult. These molecules include juvenile hormone, which is known to alter caste fate, and numerous proteins that control how social insects grow and develop. Molecules known as cuticular hydrocarbons (which allow ants to distinguish between nestmates and non-nestmates) are also transferred. (B) Adult ants also exchange fluid mouth-to-mouth, as demonstrated in this photograph (taken by LeBoeuf et al.) of two carpenter ants.

Alongside juvenile hormone, some other molecules in the saliva may also be acting as chemical signals: for example, it is known that cuticular hydrocarbons help ants to discriminate nestmates from non-nestmates (Hefetz, 2007). Furthermore, many of the proteins LeBeouf et al. identified in carpenter ants are involved in regulating the growth, development and behavior of other social insects.

This study is the first to show that trophallaxis can circulate juvenile hormone and other proteins that might be involved in larval development and caste fate around the colony. It also suggests that the ants exchange other hormones that we did not previously know were involved in communication between individuals: these hormones include hexamerin, which is known to be involved in caste fate in social insects (Zhou et al., 2007). The next challenge will be to find out whether trophallaxis really plays an active role in regulating caste fate. One way to test this idea would be to remove all the soldiers from the colony and observe whether this changes the amount of different hormones present in ant saliva as the colony attempts to replace the soldiers. Adult ants are best placed to know the needs of the colony, so it makes sense that they use several strategies to guarantee that the colony produces the right mix of castes.

References

-

The evolution of hydrocarbon pheromone parsimony in ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) - interplay of colony odor uniformity and odor idiosyncrasyMyrmecological News 10:59–68.

-

Nature versus nurture in social insect caste differentiationTrends in Ecology & Evolution 25:275–282.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.12.001

-

Developmental and physiological determinants of caste in social hymenoptera: Evolutionary implicationsThe American Naturalist 128:13–34.https://doi.org/10.1086/284536

-

The developmental basis of worker caste polymorphism in antsThe American Naturalist 138:1218–1238.https://doi.org/10.1086/285279

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: December 12, 2016 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2016, Knaden

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,923

- views

-

- 219

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Developmental Biology

- Evolutionary Biology

Despite rapid evolution across eutherian mammals, the X-linked MIR-506 family miRNAs are located in a region flanked by two highly conserved protein-coding genes (SLITRK2 and FMR1) on the X chromosome. Intriguingly, these miRNAs are predominantly expressed in the testis, suggesting a potential role in spermatogenesis and male fertility. Here, we report that the X-linked MIR-506 family miRNAs were derived from the MER91C DNA transposons. Selective inactivation of individual miRNAs or clusters caused no discernible defects, but simultaneous ablation of five clusters containing 19 members of the MIR-506 family led to reduced male fertility in mice. Despite normal sperm counts, motility, and morphology, the KO sperm were less competitive than wild-type sperm when subjected to a polyandrous mating scheme. Transcriptomic and bioinformatic analyses revealed that these X-linked MIR-506 family miRNAs, in addition to targeting a set of conserved genes, have more targets that are critical for spermatogenesis and embryonic development during evolution. Our data suggest that the MIR-506 family miRNAs function to enhance sperm competitiveness and reproductive fitness of the male by finetuning gene expression during spermatogenesis.

-

- Evolutionary Biology

- Immunology and Inflammation

CD4+ T cell activation is driven by five-module receptor complexes. The T cell receptor (TCR) is the receptor module that binds composite surfaces of peptide antigens embedded within MHCII molecules (pMHCII). It associates with three signaling modules (CD3γε, CD3δε, and CD3ζζ) to form TCR-CD3 complexes. CD4 is the coreceptor module. It reciprocally associates with TCR-CD3-pMHCII assemblies on the outside of a CD4+ T cells and with the Src kinase, LCK, on the inside. Previously, we reported that the CD4 transmembrane GGXXG and cytoplasmic juxtamembrane (C/F)CV+C motifs found in eutherian (placental mammal) CD4 have constituent residues that evolved under purifying selection (Lee et al., 2022). Expressing mutants of these motifs together in T cell hybridomas increased CD4-LCK association but reduced CD3ζ, ZAP70, and PLCγ1 phosphorylation levels, as well as IL-2 production, in response to agonist pMHCII. Because these mutants preferentially localized CD4-LCK pairs to non-raft membrane fractions, one explanation for our results was that they impaired proximal signaling by sequestering LCK away from TCR-CD3. An alternative hypothesis is that the mutations directly impacted signaling because the motifs normally play an LCK-independent role in signaling. The goal of this study was to discriminate between these possibilities. Using T cell hybridomas, our results indicate that: intracellular CD4-LCK interactions are not necessary for pMHCII-specific signal initiation; the GGXXG and (C/F)CV+C motifs are key determinants of CD4-mediated pMHCII-specific signal amplification; the GGXXG and (C/F)CV+C motifs exert their functions independently of direct CD4-LCK association. These data provide a mechanistic explanation for why residues within these motifs are under purifying selection in jawed vertebrates. The results are also important to consider for biomimetic engineering of synthetic receptors.