Computational Psychiatry: Exploring atypical timescales in the brain

The electrical activity of any region of the brain changes with time in a complex way that can be described as combinations of oscillations with different amplitudes, frequencies and phases. Different areas of the brain are also characterized by an intrinsic timescale that reflects the length of the time window over which the signals coming into that brain region are integrated (Mesulam, 1998; Honey et al., 2012).

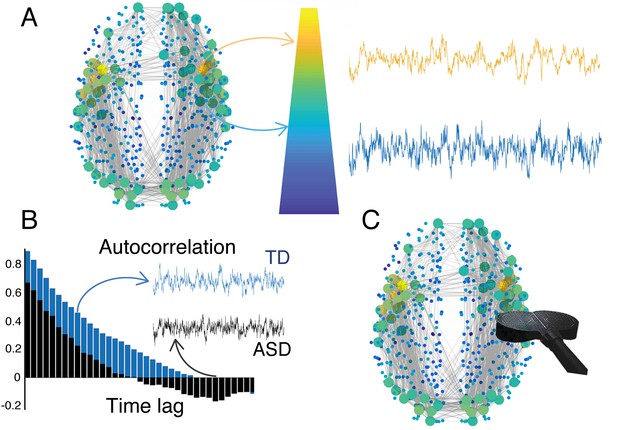

Regions with short intrinsic timescales are usually located at the periphery of the brain network and are implicated in interactions between the brain and the external world, for example, perception and movement. Regions with long timescales are usually strongly connected hubs located at the core of the brain. They are important for regulating interactions between the brain and the body, such as emotions, mood and anxiety (Gollo et al., 2015). This gradient of timescales forms a hierarchy in brain dynamics that recapitulates the hierarchy in brain structure (Kiebel et al., 2008; Murray et al., 2014; Figure 1A).

The hierarchy of timescales in the brain.

(A) The brain integrates incoming information over different timescales that are characteristic for different regions. Such a hierarchy of timescales also mirrors a hierarchy in brain structure. Brain regions located at the top of the hierarchy are represented as large (yellow) circles and have longer timescales. They are located at the core and have strong connections to other brain regions. Brain regions located at the periphery are represented by small (blue) circles and have shorter timescales. (B) Watanabe et al. found that individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD, black) have different intrinsic timescales (quantified by the autocorrelation function) compared to typically developing individuals (TD, blue). These differences correlate with the severity of symptoms of ASD. (C) In the future, non-invasive brain stimulation (black coil) may be used to selectively modulate atypical brain regions to restore their intrinsic timescales. Brain figure adapted from Gollo et al. (2018).

This hierarchy of timescales also plays an important role in perception and many other behaviors, and modifications to these timescales can be detrimental to brain function (Kiebel et al., 2008; Murray et al., 2014; Heeger, 2017). Now, in eLife, Takamitsu Watanabe, Geraint Rees and Naoki Masuda report that changes in intrinsic timescales are associated with the symptoms of autism spectrum disorder in high-functioning individuals (Watanabe et al., 2019). Their study raises the question of whether the intrinsic timescales can be used as a biomarker for neuropsychiatric disorders and as a target for potential treatment therapies.

The researchers – who are based at the RIKEN Centre for Brain Science, University College London and the University of Bristol – used functional magnetic resonance imaging to measure intrinsic timescales in people with and without a high-functioning form of autism. The results revealed that people with this form of autism have atypically short timescales in primary sensory and visual areas, while a region called the caudate, which is implicated in sensorimotor coordination, showed a longer timescale (Grahn et al., 2008). This reinforces the theory that intrinsic timescales are central to brain function, and that imbalances in specific regions substantially affect the severity of symptoms in autism spectrum disorders (Figure 1B).

Intrinsic timescales can be estimated using simple autocorrelations, which may be used to identify biomarkers and to improve our understanding of diseases and treatment plans (Figure 1B). But further research is needed to fully comprehend the causes and implications of atypical intrinsic timescales. In people with autism, shorter timescales in regions of sensory and visual cortices could relate to a heightened sensory perception, which is consistent with an excessive expectation of changes in their environment (Lawson et al., 2017). Moreover, longer timescales in the caudate might also indicate a compensation strategy to cope with an overload of sensory input due to the heightened sensory perception.

The work of Watanabe et al. opens at least two main lines of research. The first would involve mapping the timescales of brain regions across different neuropsychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia and obsessive-compulsive disorder, to determine where and what type of timescale deviations occur (King and Lord, 2011). This should also be done in healthy individuals to use their timescales as a benchmark. Depending on the location, disturbances ought to have different effects. For example, hub regions play a role in many disorders, and disturbances in their timescales may also evidence their susceptibility to dysfunction (Fornito et al., 2015; Gollo et al., 2018).

The second line of research would explore the possibility of reducing symptoms by manipulating atypical timescales, such as the ones Watanabe et al. observed in people with autism. Although drugs might not be specific enough to selectively act upon precise regions, brain stimulation could be a powerful solution (Figure 1C). For example, superficial cortical regions can be targeted by non-invasive methods such as transcranial magnetic stimulation. Moreover, recent advances suggest that brain stimulation can modify the timescale of the target region, which may be used to modulate intrinsic timescales to mitigate symptoms (Cocchi et al., 2016; Gollo et al., 2017).

Overall, the work of Watanabe, Rees and Masuda reveals how systems-level approaches hold the potential to shift paradigms in psychiatry. Translating these recent results into clinical practice will involve many practical challenges, but they may also be highly beneficial. Although many questions certainly remain, these are crucial advances on the neurobiological basis of autism.

References

-

The connectomics of brain disordersNature Reviews Neuroscience 16:159–172.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3901

-

Dwelling quietly in the rich club: brain network determinants of slow cortical fluctuationsPhilosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 370:20140165.https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0165

-

Fragility and volatility of structural hubs in the human connectomeNature Neuroscience 21:1107–1116.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-018-0188-z

-

The cognitive functions of the caudate nucleusProgress in Neurobiology 86:141–155.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.09.004

-

A hierarchy of time-scales and the brainPLoS Computational Biology 4:e1000209.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000209

-

Is schizophrenia on the autism spectrum?Brain Research 1380:34–41.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.031

-

Adults with autism overestimate the volatility of the sensory environmentNature Neuroscience 20:1293–1299.https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4615

-

A hierarchy of intrinsic timescales across primate cortexNature Neuroscience 17:1661–1663.https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3862

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: February 5, 2019 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2019, Gollo

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,588

- Page views

-

- 198

- Downloads

-

- 10

- Citations

Article citation count generated by polling the highest count across the following sources: Crossref, PubMed Central, Scopus.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Neuroscience

Mechanosensory neurons located across the body surface respond to tactile stimuli and elicit diverse behavioral responses, from relatively simple stimulus location-aimed movements to complex movement sequences. How mechanosensory neurons and their postsynaptic circuits influence such diverse behaviors remains unclear. We previously discovered that Drosophila perform a body location-prioritized grooming sequence when mechanosensory neurons at different locations on the head and body are simultaneously stimulated by dust (Hampel et al., 2017; Seeds et al., 2014). Here, we identify nearly all mechanosensory neurons on the Drosophila head that individually elicit aimed grooming of specific head locations, while collectively eliciting a whole head grooming sequence. Different tracing methods were used to reconstruct the projections of these neurons from different locations on the head to their distinct arborizations in the brain. This provides the first synaptic resolution somatotopic map of a head, and defines the parallel-projecting mechanosensory pathways that elicit head grooming.

-

- Neuroscience

The presence of global synchronization of vasomotion induced by oscillating visual stimuli was identified in the mouse brain. Endogenous autofluorescence was used and the vessel ‘shadow’ was quantified to evaluate the magnitude of the frequency-locked vasomotion. This method allows vasomotion to be easily quantified in non-transgenic wild-type mice using either the wide-field macro-zoom microscopy or the deep-brain fiber photometry methods. Vertical stripes horizontally oscillating at a low temporal frequency (0.25 Hz) were presented to the awake mouse, and oscillatory vasomotion locked to the temporal frequency of the visual stimulation was induced not only in the primary visual cortex but across a wide surface area of the cortex and the cerebellum. The visually induced vasomotion adapted to a wide range of stimulation parameters. Repeated trials of the visual stimulus presentations resulted in the plastic entrainment of vasomotion. Horizontally oscillating visual stimulus is known to induce horizontal optokinetic response (HOKR). The amplitude of the eye movement is known to increase with repeated training sessions, and the flocculus region of the cerebellum is known to be essential for this learning to occur. Here, we show a strong correlation between the average HOKR performance gain and the vasomotion entrainment magnitude in the cerebellar flocculus. Therefore, the plasticity of vasomotion and neuronal circuits appeared to occur in parallel. Efficient energy delivery by the entrained vasomotion may contribute to meeting the energy demand for increased coordinated neuronal activity and the subsequent neuronal circuit reorganization.