Multicellularity: How contraction has shaped evolution

The Cheshire Cat in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is famous for its disappearing act: parts of its body vanish one by one until nothing remains but its ethereal grin. Scientists attempting to retrace the evolution of animals confront something equally curious. One might assume that going ever further back in evolutionary time, recently-evolved animal traits would drop away until a sort of ‘minimal animal’ remained. However, a growing body of data suggests that this minimal animal may not be an animal at all. Instead, sophisticated cellular processes once thought to be exclusive to animals are found across several unicellular eukaryotes: grins without (multicellular) cats!

So how do scientists reconstruct the deep history of multicellularity? The record for the oldest multicellular organism to be studied directly belongs to plants grown from 30,000-year-old seeds preserved in permafrost (Yashina et al., 2012). However, multicellular life is much older than this. Fossils of multicellular red algae have been dated to 1.6 billion years ago (Bengtson et al., 2017), and fossils of multicellular fungi date from about a billion years ago (Loron et al., 2019). The oldest confidently-dated animal fossils are about half a billion years old (Bobrovskiy et al., 2018). Multicellularity arose independently in plants, fungi and animals (Brunet and King, 2017). Scientists are interested in the unicellular ancestors of these groups because they want to know if each transition into multicellularity was driven by similar evolutionary forces. Unfortunately, fossils reveal little about the cell biology of these primordial organisms.

Darwin was well aware of this challenge. To reconstruct the evolutionary history of an organism, he wrote in On the Origin of Species, “we ought to look exclusively to its lineal ancestors; but this is scarcely ever possible and we are forced in each case to look to… the collateral descendants from the same original parent-form.” That is, one must hope the traits of surviving organisms reveal those of their extinct ancestors. Researchers now know that Darwin’s idea of “living fossils” was too simplistic. No organism remains entirely identical to its ancestor: genetic mutations constantly accumulate, driven by conflict, competition, and random chance. Nevertheless, one could hope to reconstruct the ancestor using a patchwork of different ancestral traits preserved across different surviving descendants.

A central theme of the emerging field of evolutionary cell biology is to study organisms that provide as much information as possible about the past. One way to do this is to develop new model organisms based on their position in the tree of life. As the evolution of animals is retraced, an ancestral unicellular species at the very threshold of multicellularity will eventually be reached. It is possible this species has no surviving descendants, other than the animals themselves. To find more collateral descendants, one must push further back in time. The better life’s existing diversity is sampled, the more likely that a species will be found similar to the ancestors scientists want to reconstruct.

The billion-year-old clade known as Holozoa consists of animals and closely related unicellular species, including choanoflagellates, filastereans, and ichthyosporeans. Just a decade ago this was a sparsely sampled region of the eukaryotic tree: for example, the first choanoflagellate genome was only published in 2008 (Brunet and King, 2017). Today dozens of holozoan species have been cultured, sequenced, and studied, and they are a fertile hunting ground for interesting cell biology. Importantly, the non-animal holozoans include species that can become transiently multicellular, at certain times or under certain conditions. Specifically, some choanoflagellates and ichthyosporeans have clonal multicellular life stages, while some filastereans form multicellular aggregates. But are these behaviors homologous to multicellularity in animals, and therefore representative of the ancestral state? Or are they examples of convergent evolution, driven by adaptations to similar environments?

One way to answer these questions is to resolve the molecular mechanisms that enable multicellular behavior across holozoans. Suggestively, holozoan genomes encode transcription factors and cell adhesion genes known to be essential for animal multicellularity, but the roles of these genes had not been directly demonstrated (Grau-Bové et al., 2017; Richter et al., 2018). Now, two independent teams have reported the results of studies on certain animal-like behaviors in unicellular lineages that shed light on the evolution of animal multicellularity (Figure 1).

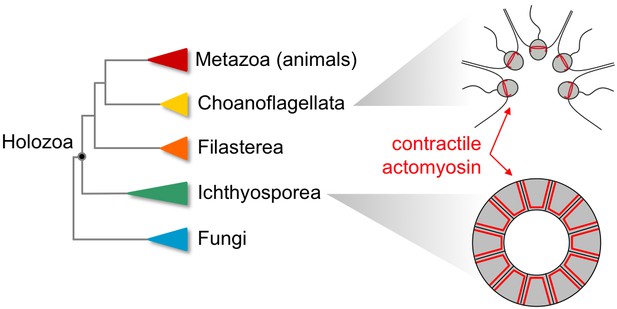

Non-animal species in the clade Holozoa exhibit coordinated contractions dependent on actomyosin complexes similar to those observed in modern animals.

Phylogenetic tree of the Holozoa showing the position of animals (Metazoa), choanoflagellates (Choanoflagellata), filastereans (Filasterea) and ichthyosporeans (Ichthyosporea) within this clade (left). The choanoflagellates include Choanoeca flexa (top right), which has flagella that point inwards when the organism is in bright light. In the dark, the cells contract in a coordinated manner that causes the flagella to point outwards, a movement reminiscent of the contractions that cause tissues to curve during animal development (figure adapted from Brunet et al., 2019). The ichthyosporean Sphaeroforma arctica (bottom right) also exhibits actomyosin contractility, invaginating its membrane to generate multiple cells out of a polarized epithelial layer. This movement is comparable to processes that occur during embryonic development in flies (Dudin et al., 2019).

In a paper in eLife, Iñaki Ruiz-Trillo and co-workers from Barcelona, Liverpool, Oslo, Shizuoka and Hiroshima – including Omaya Dudin and Andrej Ondracka as joint first authors – report how reproduction in an ichthyosporean called Sphaeroforma arctica involves a stage of growth that is reminiscent of the embryonic development of fruit flies. The nucleus of an initial single cell divides repeatedly to form a polarized epithelial layer, which then gives rise to multiple cells as its membrane undergoes coordinated invaginations (Dudin et al., 2019).

In a second paper in Science, Nicole King and co-workers from Berkeley and Amsterdam – including Thibaut Brunet, Ben Larson and Tess Linden as joint first authors – report the results of a study on a newly isolated choanoflagellate which they name Choanoeca flexa (Brunet et al., 2019). In bright light this organism exists as a cup-shaped colony of cells, with their flagella pointing inwards. In the dark, however, the cup flips inside-out via a collective cellular contraction. This collective contraction is reminiscent of the contractions that generate curvature in developing animal tissues.

Both studies use imaging and pharmacological inhibition to demonstrate that these multicellular processes depend on the same molecular machinery: complexes of actin and myosin that can generate mechanical forces within cells. These results suggest that the last common ancestor of holozoans was an organism that was capable of transient multicellularity, with cells that could contract collectively. Among its descendants, only the animals evolved a permanently multicellular lifestyle, using the power of collective contraction to sculpt tissues and generate the “endless forms most beautiful” that so inspired Darwin.

References

-

The origin of animal multicellularity and cell differentiationDevelopmental Cell 43:124–140.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2017.09.016

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: November 14, 2019 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2019, Thattai

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 3,393

- views

-

- 242

- downloads

-

- 2

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Cell Biology

Endogenous tags have become invaluable tools to visualize and study native proteins in live cells. However, generating human cell lines carrying endogenous tags is difficult due to the low efficiency of homology-directed repair. Recently, an engineered split mNeonGreen protein was used to generate a large-scale endogenous tag library in HEK293 cells. Using split mNeonGreen for large-scale endogenous tagging in human iPSCs would open the door to studying protein function in healthy cells and across differentiated cell types. We engineered an iPS cell line to express the large fragment of the split mNeonGreen protein (mNG21-10) and showed that it enables fast and efficient endogenous tagging of proteins with the short fragment (mNG211). We also demonstrate that neural network-based image restoration enables live imaging studies of highly dynamic cellular processes such as cytokinesis in iPSCs. This work represents the first step towards a genome-wide endogenous tag library in human stem cells.

-

- Biochemistry and Chemical Biology

- Cell Biology

Mediator of ERBB2-driven Cell Motility 1 (MEMO1) is an evolutionary conserved protein implicated in many biological processes; however, its primary molecular function remains unknown. Importantly, MEMO1 is overexpressed in many types of cancer and was shown to modulate breast cancer metastasis through altered cell motility. To better understand the function of MEMO1 in cancer cells, we analyzed genetic interactions of MEMO1 using gene essentiality data from 1028 cancer cell lines and found multiple iron-related genes exhibiting genetic relationships with MEMO1. We experimentally confirmed several interactions between MEMO1 and iron-related proteins in living cells, most notably, transferrin receptor 2 (TFR2), mitoferrin-2 (SLC25A28), and the global iron response regulator IRP1 (ACO1). These interactions indicate that cells with high MEMO1 expression levels are hypersensitive to the disruptions in iron distribution. Our data also indicate that MEMO1 is involved in ferroptosis and is linked to iron supply to mitochondria. We have found that purified MEMO1 binds iron with high affinity under redox conditions mimicking intracellular environment and solved MEMO1 structures in complex with iron and copper. Our work reveals that the iron coordination mode in MEMO1 is very similar to that of iron-containing extradiol dioxygenases, which also display a similar structural fold. We conclude that MEMO1 is an iron-binding protein that modulates iron homeostasis in cancer cells.