Genetic Novelty: How new genes are born

For half a century, most scientists believed that new protein-coding genes arise as a result of mutations in existing protein-coding genes. It was considered impossible for anything as complex as a functional new protein to arise from scratch. However, every species has certain genes, known as 'orphan genes', which code for proteins that are not homologous to proteins found in any other species. What do these orphan genes do, and how are they formed?

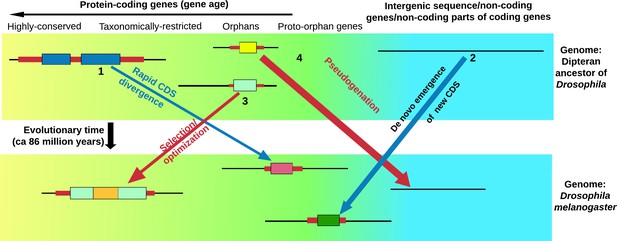

To date the roles of hundreds of orphan genes have been characterized. Although this is just a tiny fraction of the total, it is known that most of them code for proteins that bind to conserved proteins such as transcription factors or receptors. Some of these proteins are toxins, some are involved in reproduction, some integrate into existing metabolic and regulatory networks, and some confer resistance to stress (Carvunis et al., 2012; Li et al., 2009; Xiao et al., 2009; Arendsee et al., 2014; Belcaid et al., 2019). However, none of them are enzymes (Arendsee et al., 2014). Orphan genes arise quickly, so they may provide a disruptive mechanism that allows a given species to survive changes to its environment. Thus, the study of how orphan genes arise (and fall) is central to understanding the forces that drive evolution (Figure 1).

Life cycle of orphan genes.

Every species has orphan genes that have no homologs in other species. This schematic shows the genome of the fruit fly (bottom) and the genome of an ancestor of the fruit fly (top). Each panel also shows (from left to right): genes that are highly conserved and can be traced back to prokaryotic organisms (yellow background); genes that are found in just a few related species (taxonomically restricted genes), orphan genes and potential orphan genes that are not currently expressed and are thus free from selection pressure (proto-orphan genes); and regions of the genome that do not code for proteins (blue background) (Van Oss and Carvunis, 2019; Palmieri et al., 2014). An orphan gene can form through the rapid divergence of the coding sequence (CDS) of an existing gene (1), or arise de novo from regions of the genome that do not code for proteins (including the non-coding parts of genes that evolve to code for proteins; 2). Some orphan genes will be important for survival, and will thus be selected for and gradually optimized (3). This means that the genes in a single organism will have a gradient of ages (Tautz and Domazet-Lošo, 2011). Many proto-orphan genes will undergo pseudogenation (that is, they will not be retained; 4). Coding sequences (shown as thick colored bars) with detectable homology are shown in similar colors. Vakirlis et al. estimate that a minority of orphan genes have arisen by divergence of the coding sequence of existing genes.

One possible mechanism is the 'de novo' appearance of a gene from an intergenic region or a completely new reading frame within an existing gene (Tautz and Domazet-Lošo, 2011). An alternative mechanism is that the coding sequence of the orphan gene arises by rapid divergence from the coding sequence of a preexisting gene: this would mean that an entire set of regulatory and structural elements would be available to the gene as it evolves. Now, in eLife, Nikolaos Vakirlis and Aoife McLysaght (both from Trinity College Dublin) and Anne-Ruxandra Carvunis (University of Pittsburgh) report how they have studied yeast, fly and human genes to compare the contributions of these two mechanisms to the emergence of orphan genes (Vakirlis et al., 2020).

Previous studies have used simulations to estimate the number of orphan genes that appear by divergence; until now, no one had relied on actual genomics data to study this phenomenon. Vakirlis et al. use a new approach to analyze orphan genes that have originated through divergence. They examine regions of the genome that correspond to each other (so-called syntenic regions) in related species to determine whether a gene exists in both regions and, if so, whether the proteins are non-homologous. If the genes have no homology, they may have originated by rapid divergence from the coding sequence of a preexisting gene.

Using this method, Vakirlis et al. infer that at most 45% of S. cerevisiae (yeast) orphan genes, 25% of D. melanogaster (fruit fly) orphan genes, and 18% of human orphan genes arose by rapid divergence, but this is an upper estimate. For example, it is possible that a new coding sequence might have arisen de novo within an existing gene, rather than the existing coding sequence having been modified beyond recognition.

But how can a protein sequence continue to be selected for as it rapidly diverges? Vakirlis et al. suggest that divergence might occur by a process of partial pseudogenation: the existing gene becomes non-functional, and then, with no selection pressure to retain the old protein, it diverges to form an orphan gene.

Many orphan genes may not have been identified yet, because they do not have homologs in other species, and have few recognizable sequence features. This means that up to 80% of orphan genes can be missed when a new genome is annotated (Seetharam et al., 2019). The approach detailed by Vakirlis, Carvunis and McLysaght evaluates specifically those annotated orphan genes for which a similar gene exists in a related species (which is ~50% of them; Arendsee et al., 2019). As high-quality genomes from more species become available, and as more orphan genes are annotated, the approach will provide yet deeper insights into the origin of these genes.

One of the many open questions in this field deals with genes of ‘mixed age’. Some such genes have incorporated ‘chunks’ of orphans into their coding sequences. A gene that has done this is (somewhat arbitrarily) considered to be the age of its most ancient segment, but we know little about the mechanism of this process or its significance. Another question involves the unique strategies and rates of evolution of each gene (Revell et al., 2018). How might the abundance and mechanisms of orphan gene origin vary among species? And how do different environments affect the emergence of orphan genes?

References

-

Coming of age: orphan genes in plantsTrends in Plant Science 19:698–708.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2014.07.003

-

Phylostratr: a framework for phylostratigraphyBioinformatics 35:3617–3627.https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz171

-

Comparing evolutionary rates between trees, clades and traitsMethods in Ecology and Evolution 9:994–1005.https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12977

-

The evolutionary origin of orphan genesNature Reviews Genetics 12:692–702.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3053

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: February 19, 2020 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2020, Singh and Syrkin Wurtele

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 4,064

- Page views

-

- 366

- Downloads

-

- 16

- Citations

Article citation count generated by polling the highest count across the following sources: Crossref, PubMed Central, Scopus.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Cell Biology

- Computational and Systems Biology

Computer models of the human ventricular cardiomyocyte action potential (AP) have reached a level of detail and maturity that has led to an increasing number of applications in the pharmaceutical sector. However, interfacing the models with experimental data can become a significant computational burden. To mitigate the computational burden, the present study introduces a neural network (NN) that emulates the AP for given maximum conductances of selected ion channels, pumps, and exchangers. Its applicability in pharmacological studies was tested on synthetic and experimental data. The NN emulator potentially enables massive speed-ups compared to regular simulations and the forward problem (find drugged AP for pharmacological parameters defined as scaling factors of control maximum conductances) on synthetic data could be solved with average root-mean-square errors (RMSE) of 0.47 mV in normal APs and of 14.5 mV in abnormal APs exhibiting early afterdepolarizations (72.5% of the emulated APs were alining with the abnormality, and the substantial majority of the remaining APs demonstrated pronounced proximity). This demonstrates not only very fast and mostly very accurate AP emulations but also the capability of accounting for discontinuities, a major advantage over existing emulation strategies. Furthermore, the inverse problem (find pharmacological parameters for control and drugged APs through optimization) on synthetic data could be solved with high accuracy shown by a maximum RMSE of 0.22 in the estimated pharmacological parameters. However, notable mismatches were observed between pharmacological parameters estimated from experimental data and distributions obtained from the Comprehensive in vitro Proarrhythmia Assay initiative. This reveals larger inaccuracies which can be attributed particularly to the fact that small tissue preparations were studied while the emulator was trained on single cardiomyocyte data. Overall, our study highlights the potential of NN emulators as powerful tool for an increased efficiency in future quantitative systems pharmacology studies.

-

- Computational and Systems Biology

- Neuroscience

Closed-loop neuronal stimulation has a strong therapeutic potential for neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease. However, at the moment, standard stimulation protocols rely on continuous open-loop stimulation and the design of adaptive controllers is an active field of research. Delayed feedback control (DFC), a popular method used to control chaotic systems, has been proposed as a closed-loop technique for desynchronisation of neuronal populations but, so far, was only tested in computational studies. We implement DFC for the first time in neuronal populations and access its efficacy in disrupting unwanted neuronal oscillations. To analyse in detail the performance of this activity control algorithm, we used specialised in vitro platforms with high spatiotemporal monitoring/stimulating capabilities. We show that the conventional DFC in fact worsens the neuronal population oscillatory behaviour, which was never reported before. Conversely, we present an improved control algorithm, adaptive DFC (aDFC), which monitors the ongoing oscillation periodicity and self-tunes accordingly. aDFC effectively disrupts collective neuronal oscillations restoring a more physiological state. Overall, these results support aDFC as a better candidate for therapeutic closed-loop brain stimulation.