Brain Development: Why the young sleep longer

From absorbing new languages to mastering musical instruments, young children are wired to learn in ways that adults are not (Johnson and Newport, 1989). This ability coincides with periods of intense brain plasticity during which neurons can easily remodel their connections (Hubel and Wiesel, 1970). Many children are also scandalously good sleepers, typically getting several more hours of sleep per night than their parents (Jenni and Carskadon, 2007). As sleep deprivation has negative effects on learning and memory, learning like a child likely requires sleeping like one (Diekelmann and Born, 2010). Yet, how the ability to sleep for longer is synchronized with windows of high brain plasticity is not fully understood.

Sleep is deeply conserved through evolution, and examining how it develops in ‘simple organisms’ should provide fundamental insights relevant to humans. For instance, like human teenagers, one-day old Drosophila melanogaster flies sleep twice as much as mature adults, and disrupting the sleep of young flies has lasting effects on learning and behavior (Seugnet et al., 2011; Kayser et al., 2014). Now, in eLife, Matthew Kayser from the University of Pennsylvania and co-workers – including Leela Chakravarti Dilley as first author – report new regulatory mechanisms that promote sleep in young flies (Chakravarti Dilley et al., 2020).

The team started by searching for genes which, when knocked down, would reduce the difference in sleep duration between younger and older adult flies. A gene called pdm3 fit the bill by reducing sleep in juveniles. This gene codes for a transcription factor that belongs to a family known to regulate normal brain development. Chakravarti Dilley et al. further determined that pdm3 helps to establish correct sleep patterns for one-day-old flies during the pupal stage, when the relatively simple brain of a larva develops into the complex brain of the adult insect – a period of radical change that puts human puberty to shame.

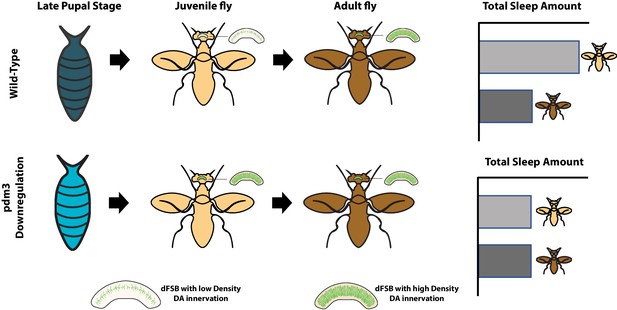

Previous work on pdm3 mutants revealed aberrations in the way dopaminergic neurons reach and connect with neurons in the central complex, a region of the brain that is known to regulate sleep. There, the dopaminergic neurons encourage wakefulness by inhibiting cells called dFSB neurons, which promote sleep (Pimentel et al., 2016). In flies, the density of connections between dopaminergic and dFSB neurons normally increases over the first few days of adult life. Chakravarti Dilley et al. therefore explored whether pdm3 might regulate how dopaminergic neurons innervate the central complex. This revealed that when pdm3 was knocked down, one-day-old flies already showed levels of innervation that rivaled those seen in mature adults (Figure 1).

How the transcription factor pdm3 preserves high levels of sleep in young flies.

Expression of pdm3 during the pupal stage (top row) delays the innervation of the dFSB neurons (which promote sleep) by dopaminergic neurons (green) that encourage wakefulness. The progressive innervation of these neurons as the fly ages results in adult flies (dark) spending less time asleep than young flies (pale). Knock down of pdm3 (bottom row) results in premature innervation, leading to young flies spending much less time asleep. dFSB: dorsal fan-shaped body; DA: dopaminergic.

Given that pdm3 encodes a transcription factor, the team then searched for genes that regulate sleep and whose expression was altered by pdm3 being knocked down. These experiments suggested that pdm3 suppresses the expression of msp300, a gene from a family involved in synapse maturation. And indeed, knocking down both pdm3 and msp300 resulted in flies that developed normally in terms of sleep patterns and dopaminergic innervation of the central complex.

Perturbing neural development, especially during windows of high plasticity, can have a long-lasting impact on the ability for the brain to work properly (Marín, 2016). A lack of sleep could lead to such perturbations, as evidenced by the fact that disrupting sleep in early childhood or adolescence has long-term effects on behavior (Taveras et al., 2017; Roberts et al., 2009). Understanding how sleep is synchronized with periods of intense development may help to develop better therapeutic interventions that lessen long-term brain damage.

References

-

The memory function of sleepNature Reviews Neuroscience 11:114–126.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2762

-

The period of susceptibility to the physiological effects of unilateral eye closure in kittensThe Journal of Physiology 206:419–436.https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009022

-

Sleep behavior and sleep regulation from infancy through adolescence: normative aspectsSleep Medicine Clinics 2:321–329.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsmc.2007.05.001

-

Sleepless in adolescence: prospective data on sleep deprivation, health and functioningJournal of Adolescence 32:1045–1057.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.03.007

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: April 27, 2020 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2020, Chowdhury and Shafer

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,888

- views

-

- 155

- downloads

-

- 2

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Genetics and Genomics

- Neuroscience

Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals the extent to which marmosets carry genetically distinct cells from their siblings.

-

- Genetics and Genomics

Telomeres, which are chromosomal end structures, play a crucial role in maintaining genome stability and integrity in eukaryotes. In the baker’s yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the X- and Y’-elements are subtelomeric repetitive sequences found in all 32 and 17 telomeres, respectively. While the Y’-elements serve as a backup for telomere functions in cells lacking telomerase, the function of the X-elements remains unclear. This study utilized the S. cerevisiae strain SY12, which has three chromosomes and six telomeres, to investigate the role of X-elements (as well as Y’-elements) in telomere maintenance. Deletion of Y’-elements (SY12YΔ), X-elements (SY12XYΔ+Y), or both X- and Y’-elements (SY12XYΔ) did not impact the length of the terminal TG1-3 tracks or telomere silencing. However, inactivation of telomerase in SY12YΔ, SY12XYΔ+Y, and SY12XYΔ cells resulted in cellular senescence and the generation of survivors. These survivors either maintained their telomeres through homologous recombination-dependent TG1-3 track elongation or underwent microhomology-mediated intra-chromosomal end-to-end joining. Our findings indicate the non-essential role of subtelomeric X- and Y’-elements in telomere regulation in both telomerase-proficient and telomerase-null cells and suggest that these elements may represent remnants of S. cerevisiae genome evolution. Furthermore, strains with fewer or no subtelomeric elements exhibit more concise telomere structures and offer potential models for future studies in telomere biology.