Dose-dependent action of the RNA binding protein FOX-1 to relay X-chromosome number and determine C. elegans sex

Abstract

We demonstrate how RNA binding protein FOX-1 functions as a dose-dependent X-signal element to communicate X-chromosome number and thereby determine nematode sex. FOX-1, an RNA recognition motif protein, triggers hermaphrodite development in XX embryos by causing non-productive alternative pre-mRNA splicing of xol-1, the master sex-determination switch gene that triggers male development in XO embryos. RNA binding experiments together with genome editing demonstrate that FOX-1 binds to multiple GCAUG and GCACG motifs in a xol-1 intron, causing intron retention or partial exon deletion, thereby eliminating male-determining XOL-1 protein. Transforming all motifs to GCAUG or GCACG permits accurate alternative splicing, demonstrating efficacy of both motifs. Mutating subsets of both motifs partially alleviates non-productive splicing. Mutating all motifs blocks it, as does transforming them to low-affinity GCUUG motifs. Combining multiple high-affinity binding sites with the twofold change in FOX-1 concentration between XX and XO embryos achieves dose-sensitivity in splicing regulation to determine sex.

Introduction

Determining sex is one of the most fundamental developmental decisions that most organisms must make. Sex is often specified by a chromosome-counting mechanism that distinguishes one X chromosome from two: 2X embryos become females, while 1X embryos become males (Bull, 1983; Charlesworth and Mank, 2010). The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans determines sex with high fidelity by tallying X-chromosome number relative to ploidy, the sets of autosomes (X:A signal) (Madl and Herman, 1979; Nigon, 1951). The process is executed with remarkable precision: embryos with ratios of 1X:2A (0.5) or 2X:3A (0.67) develop into fertile males, while embryos with ratios of 3X:4A (0.75) or 2X:2A (1.0) develop into self-fertile hermaphrodites. Here we dissect molecular mechanisms by which the X:A signal specifies sex and thereby discover how small quantitative differences in intracellular signals can be translated into dramatically different developmental fates.

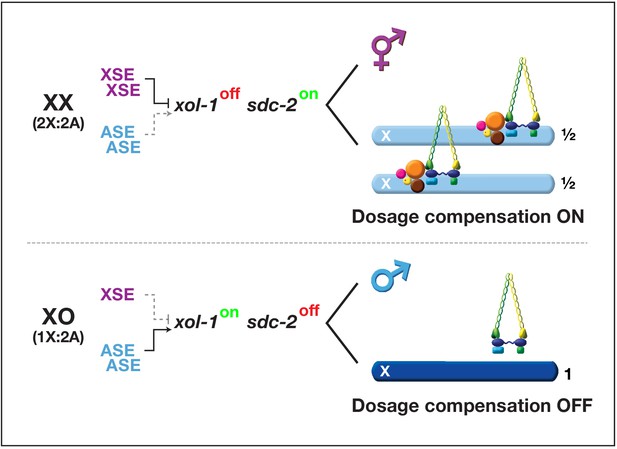

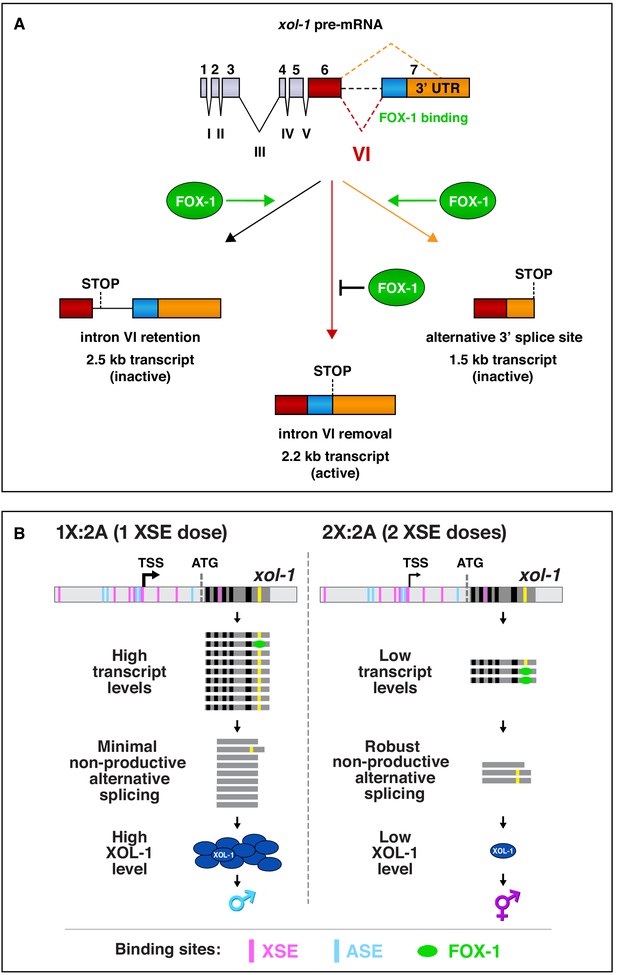

The X:A signal determines sex by controlling the activity of its direct target, the master sex-determination switch gene xol-1 (XO lethal) (Figure 1; Carmi et al., 1998; Farboud et al., 2013; Meyer, 2018; Miller et al., 1988; Nicoll et al., 1997; Powell et al., 2005; Rhind et al., 1995). xol-1 encodes a GHMP kinase that must be activated to set the male fate and repressed to set the hermaphrodite fate (Luz et al., 2003; Rhind et al., 1995). xol-1 controls not only the choice of sexual fate but also X-chromosome gene expression through the process of X-chromosome dosage compensation (Meyer, 2018; Miller et al., 1988; Rhind et al., 1995). Males and hermaphrodites generally require the same level of X-encoded gene products despite their difference in dose of X chromosomes. A dosage compensation complex (DCC) binds to both X chromosomes of diploid XX hermaphrodites to reduce transcription by half and thereby equalize X-linked gene expression with that from the single X of diploid XO males (Figure 1; Chuang et al., 1994; Chuang et al., 1994; Csankovszki et al., 2009; Dawes et al., 1999; Lieb et al., 1998; Mets and Meyer, 2009; Mets and Meyer, 2009; Meyer, 2018; Pferdehirt et al., 2011; Tsai et al., 2008; Tsai et al., 2008; Wheeler et al., 2016). The DCC resembles condensin, a chromosome remodeling complex required for the compaction and resolution of mitotic and meiotic chromosomes prior to their segregation during division (Hirano, 2016; Meyer, 2018; Yatskevich et al., 2019). Failure to activate dosage compensation kills all hermaphrodites. If xol-1 is inappropriately activated in diploid XX animals, the DCC cannot bind to X chromosomes, and all hermaphrodites die from elevated X expression. Conversely, if xol-1 is inappropriately repressed in diploid XO males, the DCC binds to the single X chromosome and kills all males by reducing X expression. Thus, the X:A signal determines the choice of sexual fate and sets the level of X-chromosome gene expression.

Overview of the X:A signal and regulatory hierarchy that control sex determination and X-chromosome dosage compensation.

The X:A signal includes a set of genes on X called X-signal elements (XSEs) that repress their direct target gene xol-1 (XO lethal) in a cumulative dose-dependent manner via transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms and set of genes on autosomes called autosomal signal elements (ASEs) that stimulate xol-1 transcription in a cumulative dose-dependent manner. xol-1 is the master sex-determination switch gene that must be activated in XO animals to set the male fate and must be repressed in XX animals to permit the hermaphrodite fate. xol-1 triggers male sexual development by repressing the feminizing switch gene sdc-2 (sex determination and dosage compensation). sdc-2 induces hermaphrodite sexual development and triggers binding of a dosage compensation complex (DCC) to hermaphrodite X chromosomes to repress gene expression by half. xol-1 mutations enable the DCC to bind to the single male X chromosome and thereby kill all XO animals by causing reduced X-chromosome expression. The dying xol-1 XO mutant animals are also feminized. Hence, mutations that disrupt elements of the X:A signal transform sexual fate and also alter X-chromosome gene expression.

Our prior studies identified a set of genes on X chromosomes called X-signal elements (XSEs) that communicate X-chromosome dose by repressing xol-1 in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1; Akerib and Meyer, 1994; Carmi et al., 1998; Gladden et al., 2007; Gladden and Meyer, 2007; Hodgkin et al., 1994; Nicoll et al., 1997). In addition, a set of genes on autosomes called autosomal signal elements (ASEs) communicates the ploidy by stimulating xol-1 activity in a cumulative, dose-dependent manner to counter XSEs (Figure 1; Farboud et al., 2013; Powell et al., 2005). Two of the XSEs, the nuclear hormone receptor SEX-1 and the homeodomain protein CEH-39, as well as two of the ASEs, the T-box transcription factor SEA-1 and the zinc finger protein SEA-2, bind directly to multiple, non-overlapping sites in 5' transcriptional regulatory regions of xol-1 (Farboud et al., 2013). XSEs and ASEs antagonize each other's opposing transcriptional activities to control xol-1 transcript levels. The X:A signal is thus transmitted in part through multiple antagonistic molecular interactions carried out on a single promoter to regulate transcription (Farboud et al., 2013). Fidelity of X:A signaling is enhanced by a second tier of dose-dependent xol-1 repression, via the XSE called FOX-1 (Feminizing locus On X), an RNA binding protein that includes an RNA recognition motif (RRM) (Akerib and Meyer, 1994; Hodgkin et al., 1994; Nicoll et al., 1997; Skipper et al., 1999).

The cumulative, dose-dependent action of XSEs was revealed by key genetic observations. For example, deleting one copy of ceh-39 and sex-1 from XX animals caused no lethality, but deleting one copy of ceh-39, sex-1, and fox-1 killed more than 70% of XX animals, and deleting one copy of all genetically identified XSEs killed all XX animals (Akerib and Meyer, 1994; Carmi and Meyer, 1999; Farboud et al., 2013; Gladden et al., 2007). In reciprocal experiments, duplicating one copy of fox-1 killed 25% of XO animals, while duplicating fox-1 and ceh-39 killed 50% of XO animals, and duplicating one copy of all genetically identified XSEs killed all XO animals (Akerib and Meyer, 1994; Carmi and Meyer, 1999; Nicoll et al., 1997).

Our current study analyzes the mechanism of FOX-1 action in regulating xol-1. fox-1 was discovered originally through a mutation that suppressed the XO lethality caused by a large X duplication shown later to include multiple XSEs (Akerib and Meyer, 1994; Hodgkin et al., 1994; Nicoll et al., 1997). FOX-1 is the founding member of an ancient family of sequence-specific RNA binding proteins that are conserved from worms to humans (Akerib and Meyer, 1994; Conboy, 2017; Hodgkin et al., 1994; Nicoll et al., 1997). Recent experiments show that mammalian FOX family members recognize and bind the primary motifs GCAUG and GCACG but also bind secondary motifs with lower affinity (Auweter et al., 2006; Begg et al., 2020; Jangi et al., 2014; Jin et al., 2003; Lambert et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2016; Modafferi and Black, 1999; Underwood et al., 2005). FOX proteins regulate diverse aspects of RNA metabolism, including alternative pre-mRNA splicing, mRNA stability, translation, micro-RNA processing, and transcription (Carreira-Rosario et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2016; Conboy, 2017; Jin et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2014b; Lee et al., 2016; Ray et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2016). FOX proteins act as developmental regulators in different tissues of many species, controlling neuronal and brain development (Begg et al., 2020; Gehman et al., 2012; Gehman et al., 2011; Kuroyanagi et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2016; Shibata et al., 2000; Underwood et al., 2005) as well as muscle formation (Gao et al., 2016; Kuroyanagi et al., 2007; Kuroyanagi et al., 2006; Singh et al., 2014; Wei et al., 2015). C. elegans FOX-1 controls sex determination by repressing xol-1 activity through a post-transcriptional mechanism that acts on any residual xol-1 transcripts present in diploid XX animals after xol-1 repression by the XSE transcription factors (Carmi and Meyer, 1999; Nicoll et al., 1997; Skipper et al., 1999). The level of this regulation, whether controlling pre-mRNA splicing, mRNA stability, nuclear transport, or translation of xol-1 RNA, had not been determined.

We demonstrate that FOX-1 represses xol-1 in XX embryos by regulating alternative xol-1 pre-mRNA splicing to inhibit formation of the mature transcript that is both necessary and sufficient for xol-1 activity in XO embryos. By binding to multiple sites in intron VI using both GCAUG and GCACG motifs, FOX-1 causes either intron VI retention or directs the use of an alternative 3' splice site, causing deletion of exon 7 coding sequences. Either alternative splicing event prevents production of essential male-specific XOL-1 proteins in XX embryos. Experiments performed in vivo demonstrate that intron VI is both necessary and sufficient for FOX-1-mediated pre-mRNA splicing regulation at the endogenous xol-1 locus and at lacZ reporters. FOX-1 RNA binding experiments performed in vitro demonstrate that FOX-1 binds to multiple GCAUG and GCACG motifs in intron VI. Genome editing of endogenous motifs coupled with functional assays in vivo demonstrate that mutation of different GCAUG and GCACG combinations reduces FOX-1-mediated repression, but only mutation of all motifs or transformation of all to low affinity GCUUG motifs blocks non-productive alternative splicing and mirrors the effect on X:A signaling of an engineered fox-1 deletion. Splicing regulation is dose-dependent: mutating one copy of fox-1 or all binding motifs in one copy of xol-1 kills XX animals sensitized by reduced XSE activity. In contrast, conversion of all endogenous intron VI motifs to either GCAUG or GCACG permits normal splicing regulation, indicating that GCACG motifs are as effective as GCAUG motifs in promoting FOX-1 binding and splicing regulation. Hence, the number of high-affinity motifs is critical. Utilizing multiple high-affinity binding sites to elicit alternative splicing amplifies the X signal by permitting the concentration of FOX-1 made from two doses of fox-1 in XX embryos to reach the threshold level necessary to inhibit XOL-1 production.

Results

An in vivo assay to determine regions of xol-1 essential for repression by FOX-1

Prior studies showed that the RNA binding protein FOX-1 determines sex by repressing xol-1 via a post-transcriptional mechanism, but the molecular basis of this regulation was not established (Carmi and Meyer, 1999; Nicoll et al., 1997; Skipper et al., 1999). We therefore devised an assay to identify regions of xol-1 necessary for repression by FOX-1. Our prior experiments showed that overexpression of FOX-1 by itself is sufficient to repress endogenous xol-1 activity, causing XO embryos to adopt the hermaphrodite sexual fate and die from reduced X-chromosome expression triggered by binding of the DCC to the single X (Nicoll et al., 1997). Hence, our strategy to identify FOX-1 regulatory sites was to assay deletion derivatives of a xol-1 transgene controlled by the native xol-1 promoter for responsiveness to FOX-1 repression in strains lacking the endogenous xol-1 gene.

The wild-type xol-1 transgene included all xol-1 genomic sequences, and an insertion of gfp sequences in frame at the first ATG codon of xol-1. Expression of wild-type transgenes and deletion derivatives was monitored in xol-1(null) mutant strains by functional assays of XOL-1 activity. XX animals are very sensitive to the dose of xol-1, and extra-chromosomal arrays carrying wild-type xol-1 transgenes could only be established using a 20–30-fold lower concentration of xol-1 DNA than typical for routine markers (see Materials and methods). Wild-type transgenes in all seven independent arrays exhibited proper sex-specific regulation: XO animals were rescued from lethality caused by the endogenous xol-1(null) mutation, and XX animals were viable (Figure 2A). The proportion of XX versus XO animals in each line was in agreement with the expected ratio (2:1) from the male-producing mutation him-5(e1490) present in all lines. However, the xol-1(+) transgenes were expressed in XX animals at a somewhat higher level than the endogenous xol-1 gene: the seven XX array lines could only be maintained if both endogenous copies of fox-1 were wild type. The observation that fox-1 mutations kill XX animals carrying wild-type xol-1 transgenes shows the need for stringent xol-1 repression in hermaphrodites by both transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms.

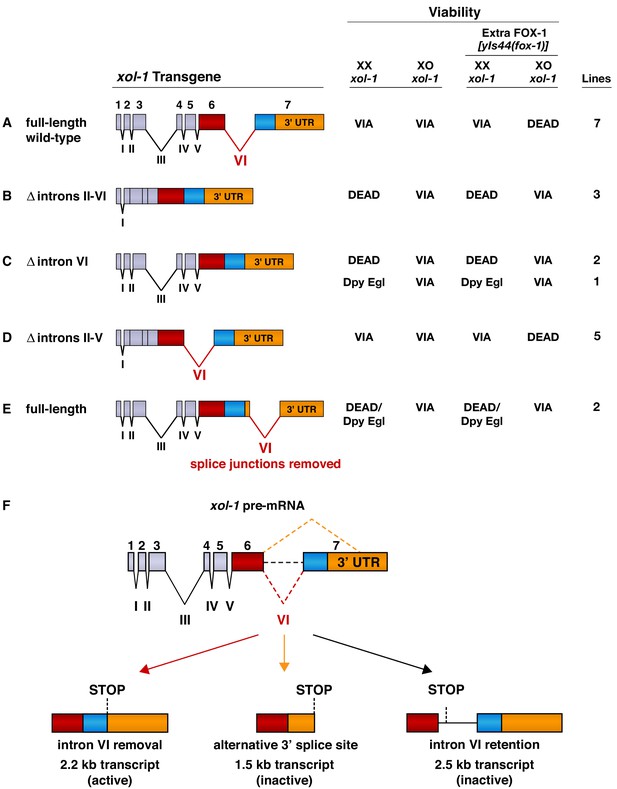

Intron VI is essential for repression of xol-1 by FOX-1.

(A–E) Assays of wild-type xol-1 transgenes and deletion derivatives with different combinations of introns show that removal of intron VI prevents FOX-1 from repressing xol-1. Diagrams on the left show the intron–exon structure of xol-1 sequences in the transgene derivatives. Exon 7 includes both coding sequences (blue) and the 3' UTR (orange). The wild-type parent transgene rescues the XO-specific lethality caused by xol-1 null mutations but permits XX animals to be viable. Intron deletion derivatives have genomic regions of xol-1 replaced by corresponding xol-1 cDNA to remove introns without altering protein coding sequence. Shown on the right is the viability of XX and XO xol-1(y9) deletion mutant animals carrying extra-chromosomal arrays of the different transgene derivatives. The arrays were made and assayed in him-5(e1490); xol-1(y9) mutants that produce 33% XO and 67% XX embryos and then crossed into him-5; xol-1 strains producing high levels of FOX-1 from an integrated array [yIs44 (fox-1)] carrying multiple copies of fox-1. The far right shows the number of independent extra-chromosomal arrays assayed. The term ‘dead’ means that all animals of the genotype were inviable, and no extra-chromosomal arrays could be established in XX animals. The arrays could only be established and maintained through XO males. The term ‘via’ means the animals were viable and appeared wild type. The term ‘Dpy Egl’ refers to the phenotype of dosage-compensation-defective XX animals that escape lethality. XX animals are typically dumpy (Dpy) in body size and egg-laying defective (Egl). The term ‘dead/Dpy Egl’ means that most animals (greater than 90%) were dead, and rare escapers were Dpy Egl. High levels of FOX-1 kill all XO animals only if a spliceable form of intron VI is present. FOX-1 does not repress xol-1 in XO animals if intron VI is absent or is relocated to the 3' UTR without splice junctions. Transgenes lacking intron VI kill XX animals, as do wild-type xol-1 transgenes in strains with a fox-1 null mutation, because all transgenes are expressed at a somewhat higher level than the endogenous xol-1 gene in XX animals. (F) Structures of the three most abundant splice variants of xol-1 transcripts are shown. Only the 2.2 kb variant, which lacks intron VI (red dashed line) and includes essential exon 7 coding sequences (blue) and 3' UTR, is necessary and sufficient for survival of XO animals. This isoform corresponds to Wormbase.org transcript C18A11.5b.1. Transcripts that retain intron VI (2.5 kb isoform corresponding to Wormbase.org transcript C18A11.5c.1) (black dashed line) or lack exon 7 coding sequences (1.5 kb isoform corresponding to Wormbase.org transcript C18A11.5a) (orange dashed line) due to use of an alternative 3' splice acceptor site cannot produce essential XOL-1 male-determining proteins.

-

Figure 2—source data 1

xol-1 transcription is not repressed by high levels of FOX-1.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/62963/elife-62963-fig2-data1-v3.docx

For XO animals with wild-type xol-1 transgenes, excess FOX-1 protein expressed from an integrated array [yIs44(fox-1)] carrying multiple copies of the fox-1(+) gene was lethal (Figure 2A; Nicoll et al., 1997). No XO animals were viable in the seven lines that carried wild-type xol-1 transgenes and expressed high FOX-1 levels. Although GFP fluorescence was XO-specific when produced from wild-type transgenes, it proved to be too insensitive a monitor for changes in xol-1 activity and was not used as part of our subsequent assays.

Deletion derivatives of xol-1 transgenes lacking FOX-1 regulatory sequences are predicted to be insensitive to repression by excess FOX-1, allowing xol-1(null) XO animals to be rescued and fully viable. Deletion derivatives lacking FOX-1 regulatory regions are also expected to kill XX animals or cause visible dosage compensation defects (Dumpy and Egg-laying defective phenotypes) due to lack of repression by FOX-1. The XX lethality and other dosage compensation phenotypes should not be suppressed by excess FOX-1. Thus, the phenotypic consequences of wild-type and deletion-derivative xol-1 transgenes act as sensitive monitors of regulation by FOX-1.

Intron VI is essential for FOX-1 to repress xol-1

We first assayed the effects on XX and XO animals of xol-1 transgenes with different combinations of intron deletions to define FOX-1 regulatory regions (Figure 2A–E). The deletion derivatives were made by replacing genomic regions of xol-1 with corresponding xol-1 cDNA to remove introns without altering the protein coding sequence. Extra-chromosomal arrays carrying deletion derivatives of xol-1 transgenes were created in him-5; xol-1 strains capable of producing both XX and XO embryos and then crossed into yIs44(fox-1); him-5; xol-1 strains that produce excess FOX-1. The DNA concentrations used for the distinct deletion-bearing transgenes were the same as for xol-1(+) transgenes. Even if a transgene deletion derivative causes XX-specific lethality, the array can be recovered and maintained through array-bearing XO animals.

The three array lines created from xol-1 transgenes lacking introns II–VI (Δ introns II–VI) rescued xol-1(null) XO males, but killed all xol-1(null) XX hermaphrodites, even though the starting DNA concentration was the same as for xol-1(+) arrays (Figure 2B). Hundreds of array-bearing males were maintained for each independent array line through genetic crosses but no array-bearing hermaphrodite progeny survived, indicating that essential FOX-1 regulatory sequences had been deleted. Excess FOX-1 also failed to suppress the XX-specific lethality and failed to kill XO animals, demonstrating the necessity of intronic sequences for xol-1 repression by FOX-1 (Figure 2B).

The essential role of introns in causing the death of XO animals with elevated FOX-1 levels could reflect the specific contribution of intron VI, which undergoes alternative splicing to yield at least three different xol-1 transcript variants (Figure 2F; Rhind et al., 1995). Only the 2.2 kb variant, which lacks intron VI and includes all of exon 7, encodes a functional XOL-1 protein that has full XOL-1 activity essential for male development (Figure 2F). This 2.2 kb variant is both necessary and sufficient for full XOL-1 function in XO embryos (Rhind et al., 1995). It is the most abundant transcript of the three, accumulating to a level 10-fold higher in XO than XX embryos. A 1.5 kb variant is made from the same 5' donor in exon 6 as used for the 2.2 kb variant but a different 3' splice acceptor, one in the 3' UTR. This splicing event eliminates the coding region of exon 7, an essential exon (Rhind et al., 1995). The 1.5 kb variant does not encode xol-1 XO activity. A 2.5 kb variant results from the failure to remove intron VI. In this variant, an in-frame UAA stop codon within intron VI terminates translation prematurely, precluding production of the male-determining protein (Rhind et al., 1995).

Indeed, removal of only the alternatively spliced intron VI from the xol-1 transgene (Δ intron VI) in all three independent lines permitted all XO animals to be viable and to escape lethality caused by high levels of FOX-1 (Figure 2C). Two of the lines caused complete XX-specific lethality that was not suppressed by excess FOX-1; lines were maintained through genetic crosses with array-bearing XO males (Figure 2C). A third line caused milder dosage compensation defects in XX animals that were not suppressed by excess FOX-1 and caused the animals to be sterile, likely reflecting a lower copy number of the transgene and hence less expression. The line had to be maintained through array-bearing XO animals. Thus, intron VI is essential for FOX-1 repression of xol-1.

Further analysis confirmed that introns II–V are dispensable for FOX-1 regulation. All lines carrying transgenes lacking these introns (Δ introns II–V) behaved like lines of the wild-type xol-1 transgene (Figure 2D). XX and XO xol-1 animals in each line were viable in the relative proportion expected for the him-5 mutation, and XO xol-1 males were killed by excess FOX-1.

When intron VI was removed from its normal location in xol-1 and relocated to the 3' UTR without splice junctions, FOX-1 could not repress xol-1 (Figure 2E). In two independent arrays of this transgene derivative, XO xol-1 animals were viable, despite excess FOX-1, and greater than 99% of XX animals were inviable, even with excess FOX-1. The rare viable XX animals were Dpy and Egl. Thus, the presence of intron VI does not simply enable FOX-1 to repress xol-1 by reducing mRNA stability, blocking nuclear transport of xol-1 RNA or preventing translation in the cytoplasm. Furthermore, experiments quantifying levels of all xol-1 RNA splice variants showed that high levels of FOX-1 did not diminish transcription from xol-1 or cause transcript degradation (Figure 2—source data 1). Instead, FOX-1 likely regulates xol-1 pre-mRNA splicing.

FOX-1 regulates intron retention and alternative splicing of xol-1 pre-mRNA

If FOX-1 represses xol-1 by promoting alterative splicing, elevated levels of FOX-1 that cause male lethality should change the distribution of xol-1 RNA splice variants. Specifically, the 2.2 kb splice variant that encodes male-determining activity should be reduced, while the inactive 2.5 kb variant with intron VI retention and/or the inactive 1.5 kb variant with partial exon 7 deletion should be increased. Using RNase protection assays and sequence analysis of cloned cDNAs, we show that elevated FOX-1 levels cause precisely these results (Figure 3 and Figure 3—figure supplement 1).

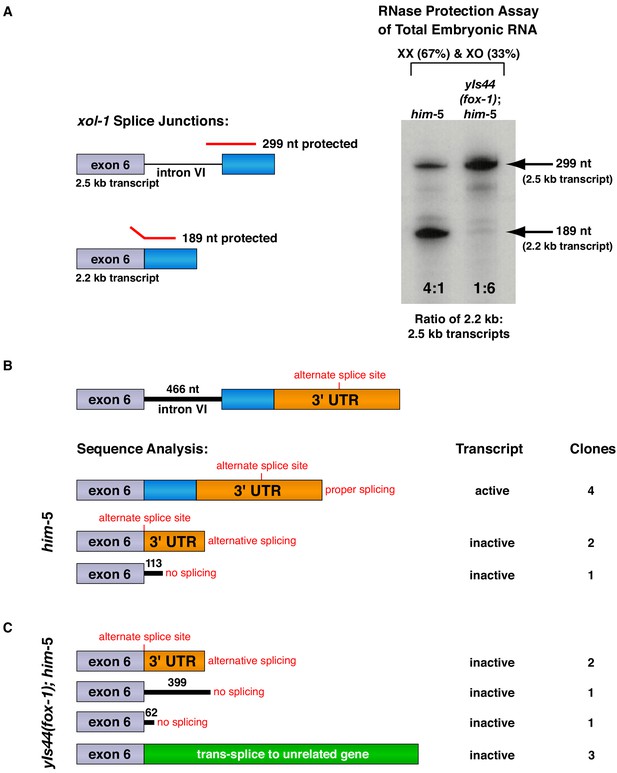

FOX-1 inhibits formation of the active 2.2 kb xol-1 transcript by promoting intron retention and alternative 3' splice acceptor selection.

(A) RNase protection assays show that FOX-1 causes intron VI retention. Shown on the left are diagrams of relevant splice junctions for exon 6 (grey) and coding sequences of exon 7 (blue) that pertain to the inactive 2.5 kb and active 2.2 kb xol-1 transcripts. Also shown are portions of the probe protected against RNase by each transcript: 299 nt for the 2.5 kb transcript and 189 nt for the 2.2 kb transcript. On the right is an image of the RNase protection assay of xol-1 transcripts in him-5 and in yIs44(fox-1); him-5 strains quantified by a phosphorimager. The probe is labeled with 32P-UTP: 43 U residues in the intron VI portion and 44 U residues in the exon 7 portion. Prior to quantifying the ratio of 2.2 kb to 2.5 kb transcripts, the 299 nt signal was divided in half to compensate for its higher number of U residues. The assay demonstrates that FOX-1 inhibits production of the male-determining 2.2 kb transcript by preventing the removal of intron VI. Levels of the act-1 control transcript were also assayed in these two RNA samples (Figure 3—figure supplement 1D). Quantification of a separate RNase protection experiment using this pMN86 probe is shown in Figure 3—figure supplement 1B. (B, C) Sequence analysis of cDNA clones from xol-1 transcripts shows that FOX-1 causes intron VI retention and also alternative 3' splice acceptor selection in xol-1. FOX-1 also causes trans-splicing of xol-1 pre-mRNA to pre-mRNA of unrelated genes. Below the diagram of xol-1's relevant intron–exon structure (exon 6 in grey and exon 7 coding sequences in blue) are diagrams representing the splicing pattern revealed by DNA sequence analysis of xol-1 cDNAs from him-5 (B) and from yIs44(fox-1); him-5 strains (C). Also shown are the predicted xol-1 activity states of transcripts with the different splicing patterns and the number of cDNA clones with each pattern. In instances of intron VI retention, the number of intron VI nucleotides in each clone is shown with blue numbers. During trans-splicing (C), the proper 5' donor at the exon 6–intron VI junction was used together with a naturally occurring 3' acceptor at an intron–exon junction of an unrelated gene identified in the text. Resulting trans-splicing events had the junction expected from proper use of the 5' and 3' sites.

For RNase protection assays, RNAs from two genetically distinct embryo populations were tested for the relative abundance of specific xol-1 splice variants within each population: one RNA from him-5 mixed-stage XX and XO embryos with wild-type FOX-1 levels and one RNA from yIs44(fox-1); him-5 mixed-stage XX and XO embryos with high levels of FOX-1. These RNAs were assayed initially using an act-1 control gene probe to assess the quality and quantity of RNAs (Figure 3—figure supplement 1D). The first set of xol-1 RNase protection assays with these quantified RNAs used a xol-1 antisense probe that spanned the 3' splice junction of intron VI–exon 7 and distinguished the 2.2 kb and 2.5 kb transcripts (Figure 3A). The ratio of 2.2 kb and 2.5 kb splice variants was calculated from transcripts within each RNA population, and ratios from different populations were then compared to assess the change in transcript ratios caused by varying the FOX-1 level. XX and XO him-5 mixed embryo populations with wild-type levels of FOX-1 showed a fourfold accumulation of active 2.2 kb transcript relative to the unspliced 2.5 kb transcript. In contrast, XX and XO populations that overexpressed FOX-1 [yIs44(fox-1); him-5] showed a drastic reduction in accumulation of the 2.2 kb transcript and a corresponding sixfold higher accumulation of the 2.5 kb transcript (Figure 3A). This experiment and repetitions (Figure 3—figure supplement 1A) established that FOX-1 promotes intron VI retention.

Transcript analysis using RT-PCR next showed that intron VI was the only intron retained in the presence of high FOX-1 levels. Using an oligonucleotide primer set that spans all six introns, RT-PCR was performed on cDNA made from the same RNAs as the protection assays. Only two PCR products were observed, one that corresponded to the 2.5 kb transcript and the other to the 2.2 kb transcript (see Materials and methods).

A second set of xol-1 RNase protection assays utilized a different antisense probe that not only distinguished between the 2.2 kb and 2.5 kb transcripts, but also detected the 1.5 kb transcript and all alternatively spliced variants that contained the 3' end of exon 6 (Figure 3—figure supplement 1B). The probe included the 3' end of exon 6 and the 5' end of exon 7. These protection experiments showed a decrease in accumulation of active 2.2 kb transcript relative to inactive 2.5 kb transcript in the presence of excess FOX-1 (2.4 to 1 with low FOX-1 and 1 to 5 with high FOX-1). They also showed a dramatic decrease in 2.2 kb transcripts compared to all spliced variants. With low FOX-1 levels, the 2.2 kb transcript was present at a ratio of 1:3, but with excess FOX-1 its accumulation decreased more than 10-fold, to a ratio of 1:38.

A third xol-1 probe differentiated the inactive 1.5 kb transcript from the combination of 2.2 kb and 2.5 kb transcripts and from all alternatively spliced transcripts that included the 3' end of exon 6 (Figure 3—figure supplement 1C). Excess FOX-1 caused the 1.5 kb transcript to increase in accumulation compared to the 2.2 kb and 2.5 kb transcripts, from a ratio of 1:14 with low FOX-1 to a ratio of 1:4 with high FOX-1. The 1.5 kb transcript also increased in accumulation compared to all splice variants present in excess FOX-1, from a 1:35 ratio to a 1:21 ratio.

This series of protection experiments demonstrated that FOX-1 represses xol-1 by controlling its pre-mRNA splicing, promoting both intron retention and also deletion of exon 7 coding sequences via alternative 3' acceptor site choice. They also reveal that excess FOX-1 causes the production of more splice variants than previously mapped. Abundance of the universal protected fragment from the 3' end of exon 6 (79 nt) relative to the protected fragments from known splice variants (191 nt and 144 nt) (Figure 3—figure supplement 1A) indicates the occurrence of unidentified splice variants caused by excess FOX-1. As a consequence, we took an alternative approach to identify splice variants by synthesizing cDNA from total embryonic RNA made from both the him-5 and the yIs44; him-5 strains and then selectively cloning and sequencing cDNAs that contained the 3' end of exon 6 (Figure 3B).

Sequences of cDNA clones from xol-1 transcripts in low FOX-1 conditions revealed only the expected: properly spliced active 2.2 kb transcripts, inactive 2.5 kb transcripts that retained intron VI, and inactive alternatively spliced 1.5 kb transcripts that deleted part of exon 7 through use of a 3' acceptor site in the 3' UTR (Figure 3B). Clones of cDNAs from high FOX-1 conditions revealed both expected and unexpected transcripts (Figure 3C). As expected, no active 2.2 kb transcripts were found, but splice variants that retained intron VI or deleted exon 7 were found. Unexpectedly, several cDNAs corresponded to xol-1 transcripts that had been trans-spliced to unrelated genes. This splicing involved the 5' donor at the exon 6–intron VI splice junction, permitting inclusion of exon 6, but then utilized an naturally occurring 3' acceptor site at an exon from an unrelated gene on chromosome II, either flcn-1, polyg-1, or K02E7.12, thus achieving accurate trans-splicing. Thus, the process by which FOX-1 enhances intron retention during RNA processing also promotes the use of alternative 3' acceptor sites, causing deletion of exon coding sequences and enabling trans-splicing.

Promiscuous fox-1-mediated trans-splicing that fuses partially spliced xol-1 transcripts onto transcripts from unrelated genes may result from the normal 3' acceptor site in xol-1 exon 7 being unavailable to receive the primed 5' splice donor in exon 6, perhaps because the 3' site is blocked or not yet synthesized. The primed 5' site then fuses with a nearby available 3' acceptor site, whether or not the site is in xol-1 or an unrelated gene. Analysis of recovered promiscuous splicing events revealed xol-1 transcripts spliced not only to transcripts from chromosome II genes, but also, and even more frequently, to transcripts from adjacent genes encoded on transgenic arrays that include xol-1. Although trans-splicing between a common 22 nucleotide SL-1 or SL-2 leader sequence and the 5' end of nascent transcripts has been well documented in C. elegans (Blumenthal, 2012), trans-splicing of exons from two different protein-coding genes has not been reported previously. In contrast, developmentally programmed trans-splicing has been observed in Drosophila for neighboring genes (Büchner et al., 2000; Dorn et al., 2001; Gabler et al., 2005; Horiuchi et al., 2003; Labrador et al., 2001).

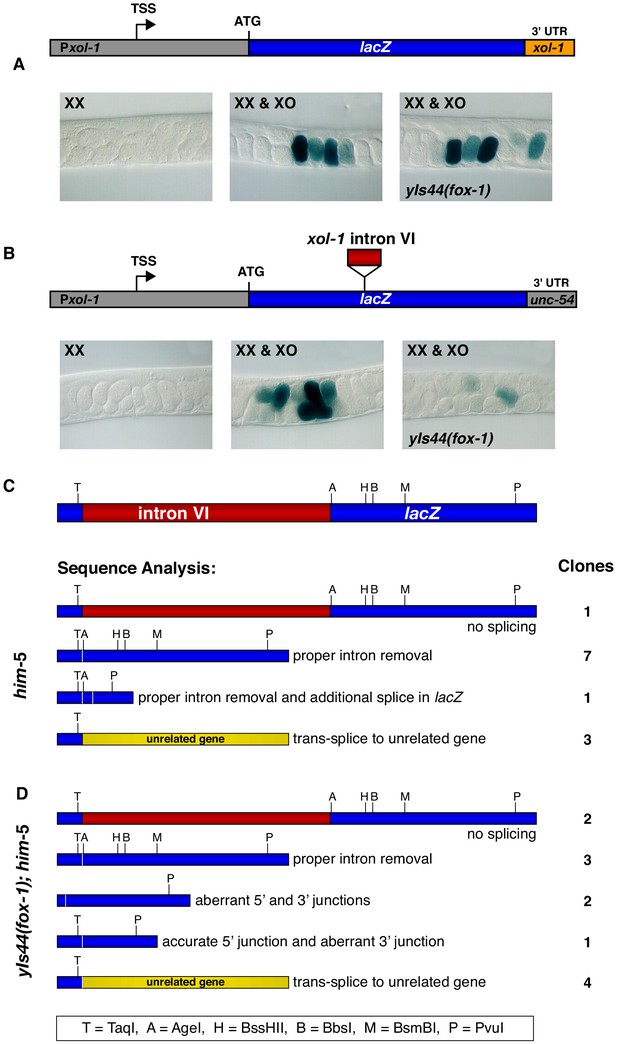

Intron VI is sufficient for FOX-1-mediated repression

To understand the mechanism by which FOX-1 regulates intron splicing, we asked whether intron VI is sufficient to confer FOX-1 repression upon a heterologous transcript (Figure 4A,B). We placed xol-1's 466 bp intron VI into the fifth exon of a lacZ reporter gene driven by the xol-1 promoter and tested whether excess FOX-1 from yIs44(fox-1) could prevent its expression (Figure 4B). The reporter gene also included the 3' UTR from the unc-54 myosin gene to assess whether intron VI by itself, without the 3' UTR from xol-1, can confer FOX-1-mediated repression. Four independently derived lines with extra-chromosomal arrays carrying the Pxol-1::lacZ::intron VI::unc-54 3' UTR reporter exhibited proper sex-specific regulation, expressing β-galactosidase at high levels in XO embryos (Figure 4B, see XX and XO images) and low levels in XX embryos (Figure 4B, see XX image), as did five independently derived lines with control Pxol-1::lacZ::xol-1 3' UTR reporter arrays that lacked intron VI and had a 3' UTR from xol-1 (Figure 4A, see XX vs. XX and XO images). Excess FOX-1 caused a marked decrease in the frequency and intensity of embryonic β-galactosidase expression in all four intron-VI-containing lines (Figure 4B, see yIs44 image) but had no effect on the five lines carrying the control lacZ reporter without intron VI (Figure 4A, see yIs44 image). At least 1000 embryos were scored for each genotype derived from each of the nine independent arrays. Therefore, intron VI by itself is sufficient to confer FOX-1 repression. These results also show that xol-1's 3' UTR is neither necessary nor sufficient for FOX-1 repression.

Intron VI of xol-1 is sufficient to confer FOX-1 repression.

(A) The promoter and 3' UTR of xol-1 are not sufficient for FOX-1 to repress xol-1. Below the diagram of the Pxol-1::lacZ::xol-1 3' UTR reporter transgene (pMN27) are sections of adult gonads from different genotypes stained with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-D-galactopyranoside. Genotypes of embryos in the gonads include: (left) XX, unc-76; yEx231 [pMN27 and unc-76 (+)]; (middle) XX and XO, him-5 unc-76; yEx231 [pMN27 and unc-76 (+)]; (right) XX and XO, yIs44(fox-1); him-5 unc-76; yEx231 [pMN27 and unc-76 (+)]. The lacZ reporter is sex-specifically regulated: high levels of β-galactosidase in XO embryos but low levels in XX embryos. High levels of FOX-1 do not diminish β-galactosidase activity in the absence of intron VI, indicating that the xol-1 promoter and xol-1 3' UTR cannot confer FOX-1 repression. Five independent extra-chromosomal array strains of each genotype carrying pMN27 showed the results represented. At least 1000 embryos were examined for each genotype derived from each of the five independent arrays. (B) Intron VI of xol-1 is sufficient for FOX-1 to repress a lacZ reporter gene. Shown is a diagram of the Pxol-1::lacZ::intronVI::unc-54 3' UTR reporter transgene (pMN110) in which the 3' UTR is from the body-wall myosin gene unc-54. Genotypes of adult gonads stained for β-galactosidase activity are the same as listed in (A), except the array is yEx280 [(pMN110) and unc-76 (+)]. This intron VI-containing lacZ reporter is also sex-specifically regulated: active in XO embryos and repressed in XX embryos. High levels of FOX-1 (from yIs44) greatly diminish the level of β-galactosidase activity in XO embryos, indicating that intron VI alone is sufficient for FOX-1 repression. Four independent extra-chromosomal array strains of each genotype carrying pMN110 showed the results represented. At least 1000 embryos were examined for each genotype derived from each of the four independent arrays. (C, D) Sequence analysis of cDNA clones from lacZ transcripts shows that excess FOX-1 increases intron VI retention and also causes alternative pre-mRNA splicing using 3' splice acceptor sites in lacZ via cis-splicing and also 3' splice acceptor sites in unrelated genes via trans-splicing. Below the diagram of lacZ's relevant intron–exon structure and restriction sites is the sequence analysis of lacZ cDNAs from him-5 (C) and from yIs44(fox-1); him-5 (D) strains. Shown are the splicing patterns revealed by DNA sequence analysis and also the number of lacZ clones with each indicated structure. During trans-splicing, the proper 5' donor at the lacZ exon–intron VI junction was used in combination with a naturally occurring 3' acceptor at an intron–exon junction of an unrelated gene (see text).

To determine whether repression of the lacZ reporter occurs by the same mechanism as repression of xol-1, we examined the splicing pattern of the reporter transcripts. cDNA was synthesized from total embryonic RNA made from intron VI-containing lacZ reporters expressed in both him-5 and yIs44(fox-1); him-5 strains. lacZ-specific PCR primer sets were used to clone lacZ transcripts from the two strains and determine the splicing pattern. Clones from XX animals with low FOX-1 levels revealed the same classes of RNA processing events in lacZ transcripts as found from RNA processing events of endogenous xol-1 RNA, consistent with intron VI conferring FOX-1 repression (Figure 4C). They included a class with proper intron VI removal, one with intron VI retention, one with proper intron VI removal plus an additional splice in lacZ sequences corresponding to the DNA region between AgeI and Pvul restriction sites, and one with the correct 5' donor site usage at the lacZ–intron VI junction but an alternative 3' splice acceptor in an exon of an unrelated gene, unc-76 (chromosome V), F58D5.5 (chromosome I), or H05L03 (chromosome X).

Clones from XX animals with high FOX-1 levels revealed five classes of transcripts consistent with transcripts from endogenous xol-1 in the presence of high FOX-1, confirming that intron VI is sufficient for FOX-1 regulation (Figure 4C). The classes included one that had proper intron VI removal, one that retained intron VI, one that used the correct 5' donor at the lacZ–intron VI junction but an alternative 3' splice acceptor in lacZ, one that had aberrant 5' and 3' junctions in lacZ, and one that used the correct 5' donor but a naturally occurring 3' splice acceptor at an exon of an unrelated gene, most commonly unc-76, but also to zen-4 (chromosome IV) and T28F4.4 (chromosome I), an ortholog of human ARMC5. The high frequency of trans-splicing, particularly to unc-76, likely results from both lacZ and unc-76 being transcribed from the same extra-chromosomal array. We conclude that repression by FOX-1 can be conferred in vivo onto a heterologous gene simply by the insertion of intron VI. Moreover, repression occurs by promoting either intron retention or use of alternative 3' acceptor sites, resulting in deletion of exon coding sequences and enabling trans-splicing.

FOX-1 binds directly to multiple sites in intron VI

Because intron VI is both necessary and sufficient for xol-1 repression by FOX-1, we developed an in vitro assay to determine whether FOX-1 regulates RNA splicing by binding directly to intron VI. Using purified FOX-1 protein and equimolar amounts of 32P-labeled RNA probe for full-length intron VI and for intron III, we performed initial cross-linking binding assays to find conditions that could permit highly specific FOX-1 binding. In experiments with increasing concentrations of FOX-1, we found that FOX-1 bound robustly to the intron VI probe, but not to the intron III negative control probe (Figure 5—figure supplement 1A). Also, intron III RNA served as a better nonspecific competitor than tRNA to inhibit nonspecific binding (Figure 5—figure supplement 1A). In competition experiments for which 32P-labeled intron VI was challenged with increasing concentrations of either cold intron III RNA or cold intron VI RNA, intron III did not compete for FOX-1 binding. In contrast, cold intron VI severely reduced FOX-1 binding to intron VI probe (Figure 5—figure supplement 1B). These results show that FOX-1 binds directly and specifically to intron VI. All subsequent binding experiments were performed in the presence of cold intron III RNA to inhibit nonspecific binding.

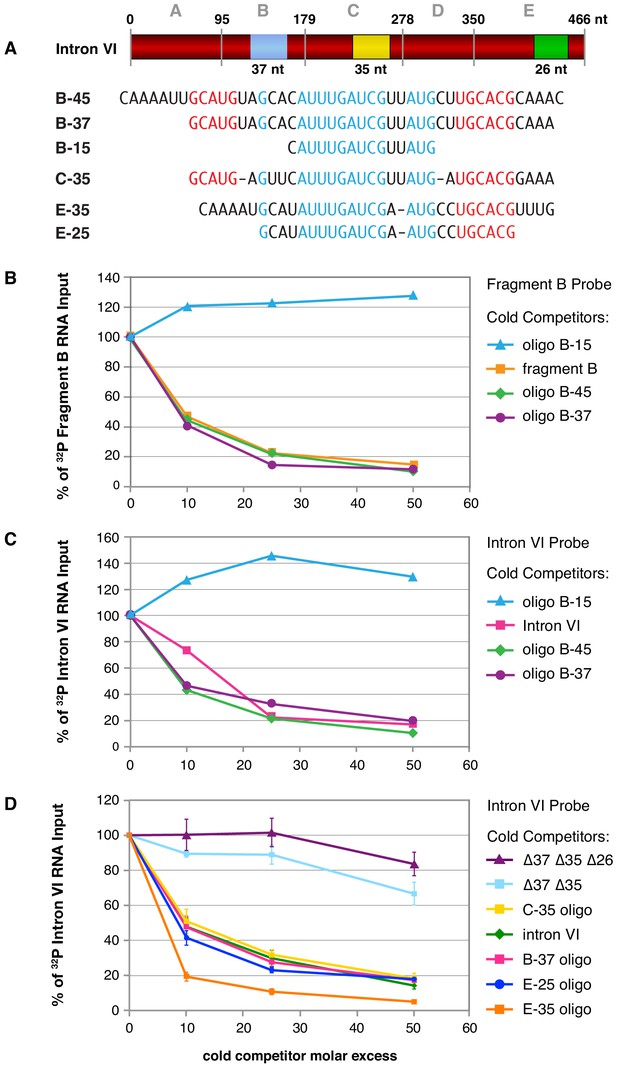

Direct binding assays with 32P-labeled RNA probes to five subregions of intron VI demonstrated specific binding to three, fragments B, C, and E (Figure 5—figure supplement 1C). Competition experiments using intron VI RNA as probe and cold RNA fragments as competitors confirmed that FOX-1 binds to multiple sites in intron VI (Figure 5—figure supplement 1D). Sequence analysis of the FOX-1 binding fragments revealed common RNA sequences within the three fragments, as delineated by B-37, C-35, and E-35 in Figure 5A.

Purified FOX-1 protein binds in vitro to multiple sites in intron VI using motifs GCAUG and GCACG.

(A) The diagram of intron VI shows the intron VI fragments (A–E) and smaller regions (RNA oligonucleotides B-45 to E-25) tested for direct FOX-1 binding in vitro. Only RNAs from fragments B, C, and E bind to purified FOX-1 (Figure 5—figure supplement 1C). Motifs GCAUG and GCACG (red) and sequences common to all three fragments (light blue) are shown below the diagram. Blue, yellow, and green rectangles indicate the locations of sequences B-37, C-35, and E-25, respectively, within FOX-1 binding fragments of intron VI. The RNA oligonucleotides listed were used in competition experiments with 32P-labeled fragment B (panel B) and 32P-labeled intron VI (panels C and D). (B) Small RNA oligonucleotides corresponding to sequences within fragment B compete for FOX-1 binding in vitro. Graphs show cross-linking competition experiments in which binding of FOX-1 (32 ng) to 32P-labeled fragment B RNA was challenged with an increasing molar excess of either cold fragment B RNA or small RNA oligonucleotides to sequences in fragment B that are also found in the other FOX-1 binding regions in fragments C and E. Binding is expressed as the percent of 32P fragment B bound by FOX-1 without any competitor RNA. (C) RNA oligonucleotides compete for FOX-1 binding to intron VI. The cross-linking competition experiments are similar to those in panel (A), except the probe is 32P-labeled full-length intron VI RNA. Binding is expressed as the percent of 32P intron VI bound by FOX-1 without any competitor RNA. The finding that the B-15 oligonucleotide fails to compete with either fragment B probe or intron VI probe, while the B-45 and B-37 oligonucleotides compete well, indicates that GCAUG, GCACG, or both are utilized for FOX-1 binding. (D) FOX-1 binds to multiple sites within intron VI using both GCAUG and GCACG. Graphs show results of cross-linking competition experiments in which binding of FOX-1 (32 ng) to 32P-labeled intron VI RNA was challenged with an increasing molar excess of several cold RNAs, as indicated. Binding is expressed as the percent of 32P intron VI RNA bound by FOX-1 without any competitor RNA. Cold intron VI RNA carrying deletions of the common sequences in B (Δ37) and C (Δ35) competed very poorly with intron VI probe for FOX-1 binding, and cold intron VI with deletions in all three common regions [B (Δ37), C (Δ35), and E (Δ26)] competed even less efficiently, demonstrating the critical role of these sequences in FOX-1 binding. In contrast, RNA oligonucleotides (C-35, B-37, E-35, and E-25) of sequences in fragments B, C, and E competed very effectively with intron VI for binding to FOX-1, further supporting the conclusion that FOX-1 binds to multiple sites in intron VI. The 25 nt RNA oligonucleotide in fragment E contains only the motif GCACG, but not GCAUG, indicating that GCACG promotes robust FOX-1 binding. The deletion in E (Δ26) is one nucleotide longer than the E-25 oligonucleotide, including deletion of a 3' U. Error bars, SEM.

To determine whether these common sequences are responsible for FOX-1 binding, we first used three RNA oligonucleotides of different sizes to fragment B in direct competition experiments against 32P-labeled fragment B probe and 32P-labeled intron VI probe (Figure 5B,C). FOX-1 binding to the B probe was eliminated not only by cold B RNA, but also by the cold 45 nt and 37 nt RNA oligonucleotides that covered the entire common fragment B sequence (Figure 5B). Thus, the common sequence is sufficient for FOX-1 binding. In addition, FOX-1 binding to 32P-intron VI probe was eliminated by both cold intron VI RNA and cold 45 nt and 37 nt fragment B RNA oligonucleotides, indicating the common sequence supports high-affinity binding that might account for all FOX-1 binding to intron VI (Figure 5C,D). Consistent with that interpretation, FOX-1 binding to 32P-intron VI was eliminated by a cold 35 nt RNA oligonucleotide to fragment C sequence and a cold 35 nt RNA oligonucleotide to fragment E sequence (Figure 5D).

In contrast, a 15 nt RNA oligonucleotide (CAUUUGAUCGUUAUG) from the middle of sequences common to all three FOX-1 binding fragments was incapable of competing for FOX-1 binding to either a fragment B probe or an intron VI probe, indicating that FOX-1 utilizes one or both of the small motifs, GCAUG and GCACG (Figure 5B,C). Both GCAUG and GCACG are in fragments B and C, but only GCACG is in fragment E.

A 25 nt RNA oligonucleotide that includes GCACG and the center of the common sequence in fragment E was sufficient to eliminate binding to an intron VI probe, indicating that GCACG promotes strong FOX-1 binding, and GCAUG is not essential for FOX-1 binding (Figure 5D). This result does not exclude the interesting possibility that GCAUG might substitute for GCACG or enhance binding to RNA that also includes GCACG.

In a final series of competition experiments, we asked whether FOX-1 binding to intron VI utilizes all three separate regions of common sequence. We compared a cold intron VI RNA competitor that lacked the common sequences in fragments B and C (∆37 ∆35) with a cold intron VI RNA competitor that lacked the common sequences in fragments B, C, and E (∆37 ∆35 ∆26) (Figure 5D). While the ∆37 ∆35 intron was a very poor competitor for the intact intron VI probe, the ∆37 ∆35 ∆26 intron was even worse; it lacked the ability to compete (Figure 5D). Thus, the three regions of common sequence contribute to FOX-1 binding in vitro and suggest they might all contribute to FOX-1 repression in vivo. The competition experiments reinforce the model that direct FOX-1 binding to intron VI facilitates intron VI retention and also causes deletion of exon 7 coding sequences by promoting use of an alternative 3' splice acceptor site.

Disruption of endogenous FOX-1 binding sites in intron VI abrogates splicing-mediated repression of xol-1 in vivo

Identification of FOX-1 binding sites in vitro led us to analyze the function of these sites in vivo for regulating xol-1 splicing and to determine the impact of xol-1 splicing regulation on X-signal activity during normal nematode development (Figure 6). Thus far, our experiments identified intron VI as the target of xol-1 splicing regulation in the context of elevated xol-1 expression caused by multiple copies of xol-1. Because elevated xol-1 expression is lethal to XX animals, these results cannot be extrapolated to disclose the full contribution of splicing regulation to X-signal activity during normal embryogenesis. The impact of splicing regulation in vivo can be determined by editing the endogenous xol-1 gene to eliminate sites used in vivo for regulation by FOX-1.

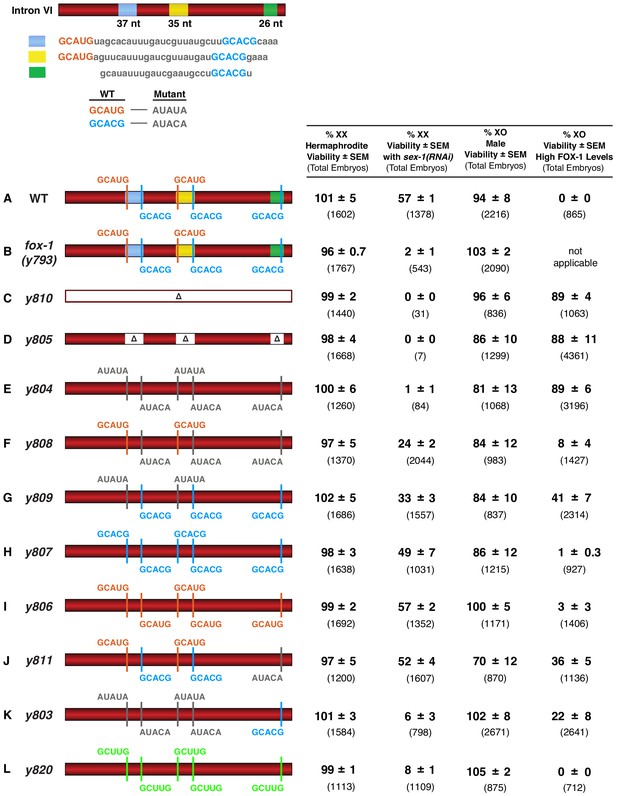

FOX-1 binds in vivo to multiple binding sites in xol-1 intron VI using both GCAUG and GCACG motifs to regulate alternative splicing.

The diagram of intron VI (top left) shows locations of the three regions (blue, yellow, and green) shown to exhibit FOX-1 binding in vitro. RNA sequences corresponding to each color-coded region are shown below the diagram. CRISPR/Cas9 editing was used to modify endogenous DNA encoding these regions and thereby identify cis-acting sites that control xol-1 splicing in vivo. The motif GCAUG was changed to AUAUA, and the motif GCACU was changed to AUACA. (A–L) Diagrams of introns with the different CRISPR/Cas9 edits used for testing xol-1 splicing regulation in vivo are shown on the left side. Multiple assays (right side) evaluate the effects on X:A signal activity of these intron mutations as well as a Cas9-induced deletion of endogenous fox-1(y793). The effects on X:A signal activity are judged by the viability of XX and XO animals with different combinations of X-signal element (XSE) levels. Viability of XX hermaphrodites with mutations only in FOX-1 regulatory regions of xol-1 measures the full contribution of splicing regulation toward X:A signal activity in the context of wild-type XSE levels and hence normal transcriptional repression by XSEs. Viability of XX xol-1 mutants treated with RNAi against the XSE gene sex-1, which encodes a nuclear hormone receptor transcriptional repressor of xol-1, monitors the synergy between transcriptional and splicing regulation when transcriptional regulation is compromised such that xol-1 expression is elevated. XX mutants were treated with sex-1(RNAi) for one generation to cause only partial sex-1 inhibition and enable 57% survival. Viability of XO xol-1 mutant animals in the context of high FOX-1 levels tests the efficacy of single and multiple FOX-1 binding sites on splicing regulation under conditions in which FOX-1 levels are not limiting for splicing regulation. The viability of xol-1 XO mutant animals with wild-type FOX-1 levels serves as a control for any adverse effects of intron VI mutations unrelated to repression by excess FOX-1. All formulae for calculating viabilities of XX and XO animals with different XSE levels are provided in Materials and methods. For all assays, the average viability of multiple broods, each from a single hermaphrodite, is shown with the standard error of the mean (SEM). The total number of embryos scored for viability from all broods is indicated in parenthesis. The experiments show that splicing regulation becomes essential when transcriptional repression is compromised. Multiple FOX-1 binding sites utilizing GCACG and GCAUG motifs are required for full splicing regulation. The number of binding sites is more critical than whether the motif sequence is GCAUG or GCACG. However, replacing all high-affinity motifs with the low-affinity secondary motif GCUUG promotes only minimal non-productive alternative splicing. High-affinity motifs are essential for FOX-1 mediated repression. Eliminating intron VI revealed no greater benefits for male viability than deleting the entire fox-1 gene.

-

Figure 6—source data 1

Overexpression of ASD-1 kills both XO males and XX hermaphrodites.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/62963/elife-62963-fig6-data1-v3.docx

The approach of removing cis-acting sites in xol-1 by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing confers three additional advantages over mutating the fox-1 gene itself for analyzing pre-mRNA splicing regulation. It cleanly separates the role of FOX-1 in sex determination from its roles in other developmental processes, revealing a more precise understanding for the contribution of alternative splicing regulation to the X signal. Furthermore, eliminating intron VI blocks all RNA binding proteins and accessory factors from participating in xol-1 splicing, potentially revealing a larger role for splicing regulation in communicating the X signal than simply achieved by FOX-1 alone. Lastly, disrupting individual FOX-1 binding sites allows us to determine the specific sites used for splicing regulation and the number of sites needed to convey the effect of a twofold difference in FOX-1 dose between XO and XX embryos to specify sex. Repression through multiple sites has the potential to amplify the small change in FOX-1 concentration between sexes by minimizing aberrant splicing with one dose of fox-1 to allow high xol-1 activity for male development and by increasing aberrant splicing with two doses of fox-1 to allow low xol-1 activity for hermaphrodite development.

We used multiple assays to judge the impact on xol-1 splicing regulation caused by disrupting endogenous FOX-1 binding sites. First, we assessed the viability of XX hermaphrodites carrying xol-1 mutations in FOX-1 regulatory regions. This assay measures the contribution of xol-1 splicing regulation toward X:A signal assessment in the context of full transcriptional repression by other X signal elements, SEX-1 (nuclear hormone receptor) and CEH-39 (homeodomain protein). Second, we assessed the viability of XX xol-1 mutant hermaphrodites in the context of reduced SEX-1 activity, and hence elevated xol-1 transcription, to measure synergy between transcriptional and splicing regulation. This sensitized XSE mutant condition was achieved using RNA interference (RNAi) against sex-1. Third, we assessed the viability of XO xol-1 mutant males in the context of high FOX-1 levels that are sufficient to kill all otherwise wild-type XO animals by causing non-productive alternative splicing. In these XO animals, the single dose of sex-1 and ceh-39 does not repress xol-1 expression. This sensitive assay measures the efficacy of single and multiple wild-type FOX-1 binding sites on splicing regulation under conditions in which FOX-1 levels are not limiting.

In initial experiments, we eliminated the non-productive alternative splicing mode of xol-1 repression using CRISPR/Cas9 editing to fuse exon 6 in frame with exon 7 at the endogenous xol-1 locus (y810) and thereby exclude intron VI from the pre-mRNA. In XO animals, removing intron VI blocked the XO-specific lethality caused by overexpressing FOX-1. Viability of XO males increased from 0% to 89% (p<10−5) for y810, indicating that splicing regulation was severely disrupted, as predicted (Figure 6A,C).

In XX animals, loss of intron VI did not reduce either the viability of mutant (y810) versus wild-type animals (99% vs. 101%, respectively) or the average brood size per hermaphrodite (240 ± 4 vs. 267 ± 32 embryos) (Figure 6—figure supplement 1A,C). Consistent with this intron VI deletion result, a null mutation of fox-1(y793) created by a Cas9-induced deletion of the entire endogenous gene also resulted in insignificant XX lethality and no reduction in brood size (Figure 6B and Figure 6—figure supplement 1B). However, just as eliminating FOX-1 activity by gene deletion killed XX hermaphrodites sensitized by reduced activity of the XSE transcription repressor SEX-1, eliminating xol-1 intron VI killed all XX hermaphrodites with reduced SEX-1 activity (Figure 6C). XX viability decreased from 57% to 2% (p<10−5) for deletion of fox-1(y793) and from 57% to 0% (p<10−5) for deletion of the intron (y810) (Figure 6C and Figure 6—figure supplement 1C). Thus, repression of xol-1 by splicing regulation in XX animals becomes critical primarily in the context of compromised transcriptional repression.

One other FOX-1 family member, the autosomal protein ASD-1, binds GCAUG motifs and controls alternative splicing of other C. elegans developmental regulators (Kuroyanagi et al., 2013; Kuroyanagi et al., 2007; Kuroyanagi et al., 2006). Our genetic evidence suggested it does not regulate xol-1 either in the presence or absence of FOX-1 (Figure 6—source data 1). That possibility could not have been fully eliminated until intron VI mutations removed the opportunity for any RNA binding factors to regulate xol-1 alternative splicing. No greater benefit to XO males or greater detriment to XX hermaphrodites occurred when all potential sources of splicing regulation were eliminated by removing intron VI rather than by deleting fox-1 alone.

FOX-1 binding sites identified in vitro function in vivo to regulate xol-1 splicing

To determine whether FOX-1 binding sites identified in vitro by biochemical analysis do indeed function in vivo to regulate xol-1 RNA splicing, we used two strategies to mutate endogenous DNA encoding these sites in intron VI. First, we deleted the 37 bp, 35 bp, and 26 bp regions corresponding to the in vitro FOX-1 binding sites (y805) (Figure 6D). Second, we altered the sequence of all individual putative binding motifs within each binding site (y804) (Figure 6E). Endogenous DNA was edited to convert the RNA motif GCAUG to AUAUA and GCACG to AUACA.

The nucleotide deletions (y805) and substitutions (y804) of all FOX-1 binding sites and motifs, respectively, within intron VI had the same effect as eliminating the intron: nearly complete loss of XX viability in the sensitized sex-1(RNAi) XSE mutant condition and suppression of male lethality caused by FOX-1 overexpression (Figure 6D,E). XX viability with sex-1(RNAi) was reduced from 57% to 0% (p<10−5) by the binding site deletions, and from 57% to 1% (p<10−5) by the motif substitutions. Male viability with high FOX-1 levels increased from 0% to 88% (p<10−5) with the deletions and from 0% to 89% (p<10−5) with the substitutions. In contrast, the viability and brood sizes of XX animals bearing only deletions or nucleotide substitutions of all FOX-1 binding sites and motifs in a sex-1(+) condition were not different from wild-type XX animals (Figure 6D,E and Figure 6—figure supplement 1D,E). These experiments indicate that FOX-1 binding sites and motifs identified in vitro do function in vivo to mediate xol-1 splicing repression, and confirm that splicing regulation is essential for hermaphrodite viability primarily in the context of reduced transcriptional repression.

Multiple GCAUG motifs and GCACG motifs in intron VI are essential for FOX-1-regulated alternative xol-1 splicing

Genome editing of fox-1 binding sites also allowed us to determine the efficacy in vivo of GCAUG motifs versus GCACG motifs in splicing-mediated xol-1 repression in XX and XO animals and to determine how many FOX-1 binding sites are required for full splicing regulation. Mutating the three GCACG motifs while retaining the two GCAUG motifs (y808) reduced the viability of sex-1(RNAi) XX animals to about half the level of sex-1(RNAi) XX animals with five wild-type motifs (24% vs. 57%) (p<10−5), but permitted more XX viability than with mutant versions of all five GCAUG and GCACG motifs (y804) (24% vs. 1%) (p<10−5) (Figure 6F and Figure 6—figure supplement 1F). These results indicate that GCACG motifs function in vivo for splicing repression in XX animals, but by themselves are not sufficient for full repression; the GCAUG motifs are also required. The two GCAUG motifs remaining in y808 also severely reduced the viability of XO animals with high FOX-1 levels compared to those with five mutant motifs (y804) (8% vs. 89%) (p<10−5), demonstrating that GCAUG motifs contribute to FOX-1-mediated repression in XO animals (Figure 6F).

Reciprocally, mutating the two GCAUG motifs while retaining the three wild-type GCACG motifs (y809) reduced the viability of XSE-sensitized XX animals by about half compared to those sensitized XX animals having all five wild-type motifs (33% vs. 57%) (p<10−4), but permitted more XX viability than all five mutant motifs (y804) (33% vs. 1%) (p<10−5) (Figure 6G and Figure 6—figure supplement 1G). These results indicate that GCAUG motifs function in vivo for splicing repression in XX animals but are not sufficient for full repression; GCACG motifs are also important. The three GCACG motifs remaining in y809 reduced the viability of XO animals with high FOX-1 levels by half compared to XO animals with all mutant motifs (y804) (41% vs. 89%) (p<10−5) (Figure 6G), indicating that GCACG motifs contribute to splicing regulation in XO animals. Thus, multiple FOX-1 binding sites are required in vivo for xol-1 repression by alternative splicing, and both GCACG and GCAUG motifs are important.

To determine whether GCACG motifs alone or GCAUG motifs alone could be sufficient for full splicing-mediated repression when present at all five sites, we converted all five motifs to either GCACG (y807) or GCAUG (y806) (Figure 6H,I and Figure 6—figure supplement 1H,I). When present in all sites, either GCACG or GCAUG motifs were sufficient to confer complete splicing repression, just like a wild-type intron VI. Virtually all XO animals were killed by high levels of FOX-1 (1% or 3%, respectively, vs. 0%), and the viability of XSE-sensitized XX animals was equivalent to that achieved with a wild-type intron VI (49% or 57%, respectively, vs. 57%) (Figure 6H,I). These results indicate that the number of binding sites is more important than whether the sequences are GCAUG or GCACG.

The significance of motif number in splicing repression is further illustrated by additional experiments. First, XX viability was compared directly between edited animals that have only GCAUG motifs but differ in GCAUG number. Viability of sex-1(RNAi) XX animals with five GCAUG motifs (y806) was 57%, but viability with two GCAUG motifs was 24% (p<10−4) (Figure 6I and Figure 6—figure supplement 1I). Second, viability of sex-1(RNAi) XX animals was relatively normal with four of five wild-type motifs (y811) (52% vs. 57%) (Figure 6J and Figure 6—figure supplement 1J). However, viability of sex-1(RNAi) XX animals was reduced when xol-1 had just two or three wild-type motifs: 24% (p<10−5) for two GCAUG motifs in y808% and 33% (p<10−4) for three GCACG motifs in y809 (Figure 6F,G). Third, mutation of a single motif, the terminal GCACG motif (y811), was sufficient to reduce splicing-mediated repression of xol-1 in XO animals by high FOX-1 levels (Figure 6J). More XO animals with excess FOX-1 were viable with only four of five wild-type motifs (y811) than with all five (36% vs. 0%). Fourth, in a reciprocal experiment, a single GCACG motif (y803) was sufficient to decrease viability of XO animals with high FOX-1 levels compared to XO animals with no wild-type sites (y804) (22% vs. 89%) (p<10−5) (Figure 6K). Thus, in the context of high FOX-1 levels, a single GCACG motif functions in splicing repression, but increasing the number of either GCACG or GCAUG motifs causes progressively greater repression and less XO viability.

To further assess the effect of only a single FOX-1 binding site in xol-1, we examined XX animals in which only the terminal GCACG motif (y803) was present (Figure 6K and Figure 6—figure supplement 1K). We found severe XX lethality in the XSE-sensitized background (6% viable), indicating that the single GCACG site by itself is not sufficient for robust regulation in XX animals. Multiple sites are required, as exemplified from the increased viability of sex-1(RNAi) XX animals with three GCACG motifs (33%, p<10−5) (Figure 6G) and five GCACG motifs (49%, p=0.01) (Figure 6H).

The fact that 6% of XX animals were viable with just the single site (y803) instead of 1% (p=0.002) when all sites were altered (y804) indicates that the GCACG site by itself permits sufficient alternative splicing to rescue some XX animals (Figure 6E,K). Utility of the single site is also reflected in the brood size of these XSE-sensitized animals. Hermaphrodites with one GCACG site had an average brood size of 100 ± 25 embryos, while those with no sites had an average brood size of 11 ± 4 embryos (Figure 6—figure supplement 1E,K). Consistent with the efficacy of a single GCACG site, viability of XO animals in the presence of high FOX-1 levels was reduced from 89% when all sites were absent (y804) to only 22% (p<10−5) when a single GCACG site (y803) was present (Figure 6E,K). Thus, while one binding site can achieve some repression, multiple sites are needed for full repression, thereby creating a sensitive mechanism for xol-1 regulation by FOX-1.

No GCAUG or GCACG motifs are present in any xol-1 intron other than intron VI, consistent with intron VI being sufficient for FOX-1 regulation. Two GCACG motifs are present in the 3' UTR of the 2.2 kb transcript, but this 3' UTR is not necessary for repression by FOX-1 (Figure 4B).

Multiple low-affinity GCUUG motifs in intron VI are not sufficient to repress xol-1 with the FOX-1 levels present in wild-type XX or XO animals but are sufficient for xol-1 repression in both sexes with high FOX-1 levels

Recent studies demonstrated that mammalian Rbfox can utilize secondary, low-affinity binding motifs such as GCUUG to promote alternative splicing in vivo if these motifs are present in multiple copies, and if Rbfox reaches a concentration higher than necessary for binding to GCAUG motifs (Begg et al., 2020). Therefore, we tested whether replacing all GCACG and GCAUG motifs in intron VI with GCUUG motifs would promote sufficient non-productive splicing in the presence of high FOX-1 levels to cause the death of XO males and, reciprocally, the survival of XX embryos exposed to sex-1(RNAi). In XO animals with high FOX-1 levels, the low-affinity GCUUG binding sites were sufficient to cause complete XO lethality (y820 in Figure 6L).

In XX animals with wild-type GCUCG and GCACG motifs in intron VI, high levels of FOX-1 could suppress the death caused by sex-1(RNAi) (24% vs. 63% viable p=0.004) (Figure 6—figure supplement 2A,B), demonstrating that enhancing post-transcriptional repression of xol-1 can compensate for the deficiency in repression caused by reducing transcriptional repression. Although high FOX-1 levels in XX animals with mutated GCACG and GCAUG motifs could not suppress any death caused by sex-1(RNAi) (Figure 6—figure supplement 2D), high FOX-1 levels could rescue XX animals with low-affinity GCUUG motifs from sex-1(RNAi)-induced death (p=0.006) (Figure 6—figure supplement 2C), as could high FOX-1 levels with normal GCAUG and GCACG motifs.

In contrast, GCUUG motifs were not adequate to suppress the lethality caused by sex-1(RNAi) when only the two wild-type doses of fox-1 were present in XX embryos. Only 8% of y820 sex-1(RNAi) XX animals carrying GCUUG motifs survived compared to 57% survival when all sites had the original high-affinity GCAUG or GCACG motifs (p<10−3) (Figure 6L and Figure 6—figure supplement 1L). These results show that although multiple low-affinity GCUUG binding sites, coupled with high FOX-1 levels, are sufficient to kill XO animals or to suppress the death of sex-1(RNAi) XX animals, the low-affinity GCUUG sites are inadequate to repress xol-1 in XX embryos with only the normal two doses of fox-1. The degree of non-productive splicing necessary to repress xol-1 in XX embryos with two copies of fox-1 is only reached if multiple high-affinity motifs are present in intron VI.

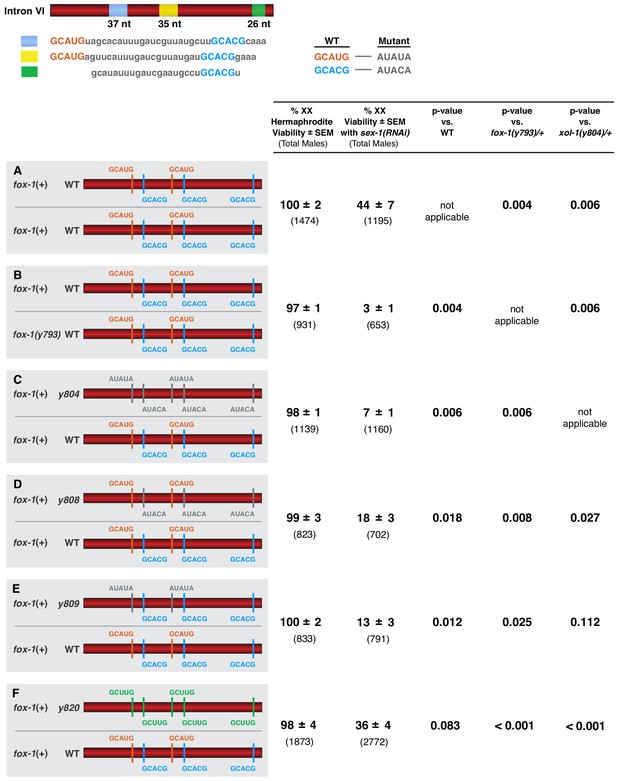

FOX-1 acts in a dose-dependent manner in XX animals to regulate xol-1 splicing and thereby determines sex

The need for multiple high-affinity binding sites to enable two doses of FOX-1 to repress xol-1 in XX animals suggested that xol-1 splicing control would be sensitive to FOX-1 dose. We took two approaches to evaluate the dose-dependence of FOX-1 action in determining sex. In XX animals with reduced sex-1 activity caused by RNAi directed against sex-1, we compared the impact on xol-1 regulation of reducing the dose of FOX-1 from two copies to one to the impact of mutating combinations of FOX-1 binding sites in one endogenous copy of xol-1. Both approaches revealed dose-sensitivity of FOX-1 action.

Viability of the sex-1(RNAi) XX animals declined more than 10-fold, from 44% to 3% (p=0.002), when the dose of fox-1 was reduced by half, from two copies to one copy, demonstrating dose-dependence of FOX-1 function in XX animals (Figure 7A,B). Similarly, viability of sex-1(RNAi) XX animals declined from 44% to 7% (p=0.006) when all FOX-1 binding sites in intron VI were mutated in one copy of xol-1 (Figure 7A,C). As expected, viability of sex-1(RNAi) XX animals declined to an intermediate level when either the three GCACG motifs (18%) (p=0.018) or the two GCAUG motifs (13%) (p=0.012) were mutated in one copy of xol-1 (Figure 7A,D,E). Viability of sex-1(RNAi) XX animals with five low-affinity GCUUG motifs in one copy of xol-1 was better (36%) than that with either two GCAUG (p=0.023) or three GCACG (p=0.017) mutated motifs in one xol-1 copy (Figure 7F). Hence, the dose-dependence of FOX-1 function in regulating alternative xol-1 splicing in XX animals is evident both from reducing the dose of the trans-acting FOX-1 protein or by mutating different combinations of cis-acting FOX-1 binding sites in only one copy of xol-1. Thus, FOX-1 acts as an XSE to convey X-chromosome number by regulating alternative xol-1 splicing in a dose-dependent manner.

FOX-1 acts in a dose-dependent manner to regulate xol-1 splicing in XX animals and thereby determine sex.

(A–F) Diagrams on the left show sequences for the two different xol-1 intron VI combinations assayed in each cohort of sex-1(RNAi) XX animals to assess the dose-dependence of FOX-1 action in regulating xol-1 splicing. Viability of both sex-1(+) and sex-1(RNAi) animals is shown on the right along with statistical comparisons of viability across different genotypes. Except for (A, B) in which both copies of intron VI have unaltered FOX-1 binding sites, one xol-1 intron VI has mutated FOX-1 binding sites as indicated and one intron has unaltered FOX-1 binding sequences (C–F). (B) Low viability of sex-1(RNAi) XX animals with only one dose of fox-1 [fox-1(y793) / +] shows strong dose-dependence of FOX-1 action in xol-1 splicing regulation. (C–F) The impact of heterozygous combinations of intron VI mutations on viability of sex-1(RNAi) XX animals also indicates that FOX-1 functions as a dose-dependent X signal element to regulate xol-1 splicing and thereby communicate X-chromosome dose. Viability assays were conducted using the protocols that follow. Separate matings were performed between Prps-0::mNeonGreen::4xNLS::unc-54 green males and hermaphrodites of genotypes: wild-type XX for (A), fox-1(y793) XX for (B), xol-1(y804) XX for (C), xol-1(y808) for (D), xol-1(y809) for (E), and xol-1(y820) for (F). For the sex-1(RNAi) experiments, matings were performed on plates with bacteria containing plasmids that produce double-stranded sex-1 RNA when XX animals were young adults. For the control set of matings, males and hermaphrodites were grown on bacteria that do not produce double-stranded sex-1 RNA (pL4440 empty vector control). For both sets of crosses, all green hermaphrodites and green males were counted. Since viability of XO animals is not affected by sex-1(RNAi), the number of green XX hermaphrodites expected if all were viable would be the same as the number of green XO males. Percent XX viability was calculated by (Number of green hermaphrodites/Number of green males) × 100.

Discussion

We dissected the mechanism by which the C. elegans RNA binding protein FOX-1 acts as a dose-dependent X-chromosome signal element to specify sexual fate. In XX embryos, FOX-1 binds to the single alternatively spliced intron of xol-1, the master regulator that sets the male fate in XO embryos, and causes either intron retention, and hence premature translation termination, or alternative 3' acceptor site usage, and hence exclusion of essential exon coding sequences (Figure 8). Both events prevent production in XX embryos of functional male-determining XOL-1 protein, which also sets the level of X-chromosome gene expression in XO embryos. FOX-1 must bind to multiple high-affinity GCAUG and GCACG motifs in xol-1 intronic sequences to regulate xol-1 splicing in XX embryos, and this splicing regulation is dose-dependent to achieve xol-1 repression in XX but not XO embryos. Deleting one copy of fox-1 or removing all FOX-1 binding sites in one copy of xol-1 reduces splicing regulation sufficiently to kill XX animals with reduced XSE activity, demonstrating the importance of fox-1 dose for viability of XX animals. Having two doses of fox-1 in XX embryos is as important for viability as restricting the dose of fox-1 to one in XO embryos.

Summary of xol-1 splicing regulation by FOX-1 and model for X:A signal assessment.

(A) Summary of xol-1 splicing regulation by FOX-1. Through binding to multiple GCAUG and GCACG motifs in intron VI of xol-1, FOX-1 reduces formation of the male-determining 2.2 kb transcript by causing intron VI retention (2.5 kb transcript) or by directing use of an alternative 3' splice acceptor site, causing deletion of essential exon 7 coding sequences (blue) and part of the 3' UTR (orange) (1.5 kb transcript). (B) Model for X:A signal assessment: two tiers of xol-1 repression. X-signal elements (XSEs) and autosomal signal elements (ASEs) bind directly to numerous non-overlapping sites in the 5' regulatory region of xol-1 to antagonize each other's opposing transcriptional activities and thereby control xol-1 transcription (Farboud et al., 2013). Molecular rivalry at the xol-1 promoter between the XSE transcriptional repressors and ASE transcriptional activators causes high xol-1 transcript levels in 1X:2A embryos with one dose of XSEs and low levels in 2X:2A embryos with two doses of XSE. All binding sites for the XSEs (nuclear receptor SEX-1 and homeodomain protein CEH-39) are shown in magenta and binding sites for the T-box transcription factor ASE called SEA-1 are shown in blue. Binding sites for the zinc finger ASE called SEA-2 have not been mapped precisely enough in this xol-1 regulatory region to represent. In a second tier of xol-1 repression shown by our studies, the XSE RNA binding protein FOX-1 (green) then enhances the fidelity of X-chromosome counting by binding to numerous GCAUG and GCAUG motifs in intron VI (yellow) of the residual xol-1 pre-mRNA, thereby causing non-productive alternative splicing and hence xol-1 mRNA variants that have in-frame stop codons or lack essential exons. High XOL-1 protein induces the male fate and low XOL-1 permits the hermaphrodite fate. Black rectangles represent xol-1 exons, dark gray rectangles represent xol-1 introns, and light gray rectangles represent 5' and 3' xol-1 regulatory regions.

Dose-dependent regulation of xol-1 splicing acts as a secondary mode of repression in XX embryos to enhance the fidelity of X:A signaling. Transcriptional repression by XSEs is the primary mode of xol-1 regulation (Carmi et al., 1998; Carmi and Meyer, 1999; Farboud et al., 2013; Gladden and Meyer, 2007; Meyer, 2018; Powell et al., 2005). We showed that non-productive alternative splicing is then imposed on residual xol-1 transcripts to achieve full xol-1 repression in XX embryos. Repression of xol-1 by splicing regulation is especially critical in the context of compromised transcriptional repression and during early development prior to maximal transcriptional repression. XX embryos lacking splicing regulation die if xol-1 transcription is even partially activated in XX embryos. Reciprocally, increasing FOX-1 concentration above the normal level in XX embryos, and hence increasing non-productive splicing, suppresses the XX lethality caused by reducing xol-1 transcriptional repression. The combined action of splicing and transcriptional repression of xol-1 enhances the precision of X-chromosome counting.

Mechanisms underlying the action of FOX family members in regulating alternative pre-mRNA splicing

Multiple high-affinity FOX-1 binding motifs are necessary to restrict the non-productive mode xol-1 splicing to XX embryos over the small FOX-1 concentration range that distinguishes XX from XO embryos. Among numerous experiments, the need for multiple high-affinity RNA binding sites to repress xol-1 was well exemplified by the comparison in XX viability of engineered xol-1 strains that carried only GCACG motifs in intron VI, but in different numbers, and were subjected to sex-1(RNAi). The viability of the XX strain with five GCACG motifs (49%) was greater than that with three GCACG motifs (33%) or with one motif (6%). Moreover, replacing all GCUAG and GCACG motifs with low-affinity GCUUG motifs permitted only minimal survival (8% vs. 57%).

In other cases of splicing regulation by C. elegans FOX-1, specifically the unc-32 and egl-15 gene targets, robust regulation is achieved through a single GCAUG binding site using a different strategy from the one for xol-1. FOX-1 binds the unc-32 pre-mRNA at the single GCAUG site in concert with the neuronally expressed CELF RNA binding protein UNC-75 to promote skipping of the upstream exon (Kuroyanagi et al., 2013). To do so, FOX-1 acts redundantly with ASD-1, another FOX-1 family member. Either FOX-1 or ASD-1 can bind the GCAUG site with UNC-75, and together regulate unc-32. Similarly, FOX-1 and ASD-1 regulate splicing of egl-15 pre-mRNA in combination with the muscle-specific RNA binding protein SUP-12 using a single GCAUG site (Kuroyanagi et al., 2007). For both gene targets, two FOX-1 family members bind a single binding site to help ensure proper splicing in conjunction with key tissue-specific RNA binding proteins. Loss of either fox-1 or asd-1 activity causes partial loss-of-function phenotypes for egl-15 and for unc-32, revealing that asd-1 and fox-1 function in a collaborative fashion to reinforce splicing control of two different pre-mRNA targets, each with one binding site (Kuroyanagi et al., 2013; Kuroyanagi et al., 2007). In contrast, our results showed that ASD-1 is not required for regulation of alternative xol-1 splicing to repress xol-1 activity in XX embryos.

For many mammalian genes, Rbfox can bind to an intron and control pre-mRNA splicing using a single high-affinity GCAUG motif. A tyrosine-rich, low-complexity domain at the C-terminus then nucleates aggregation of Rbfox to attain the concentration of bound proteins necessary to drive alternative splicing (Ying et al., 2017). Rbfox aggregation is essential for inclusion of specific exons into mature mRNA and has the potential to recruit additional splicing factors. Rbfox aggregation may also be necessary for concentrating Rbfox complexes in nuclear speckles, where RNA synthesis occurs (Ying et al., 2017). Such concentrated localization may promote binding to and alternative splicing of newly synthesized RNAs. C. elegans FOX-1 lacks a tyrosine-rich low-complexity domain to cause protein aggregation, but during xol-1 regulation, recruitment of FOX-1 through multiple intronic binding sites using GCAUG and GCACG motifs appears to substitute for protein aggregation in achieving robust alternative splicing. In this case, availability of multiple sites would increase the probability of any site being occupied.