Nanoscale Signaling: Messages across time and space

Homeostasis – the ability of an organism to maintain a stable internal environment despite changes in the outside world – is essential for cells, tissues and organs to work properly. Regulating body temperature, maintaining blood pressure or monitoring blood sugar levels are all different forms of homeostasis, and they depend on specialized sensory cells. These cells monitor the environment and the body’s condition and, if necessary, chime in to keep the body functioning properly.

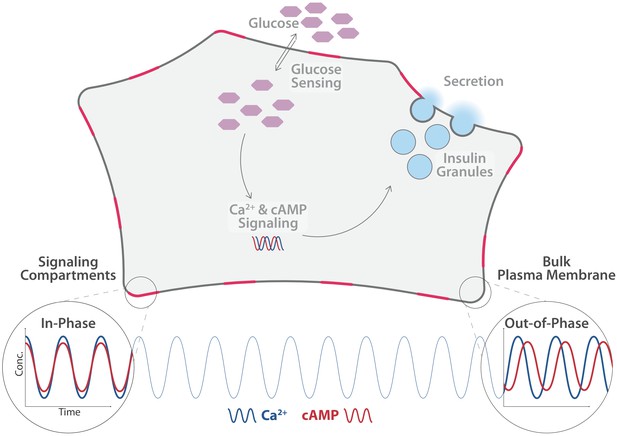

Sensory cells are, in turn, tightly regulated by so-called second messengers – small intracellular signaling molecules that control many different pathways within a cell. The β-cells in the pancreas, for example, are responsible for sensing elevated blood sugar levels and for releasing insulin. This hormone regulates how the body uses and stores glucose and fat. If excessive glucose concentrations are detected in the blood, second messenger molecules in the β-cells, such as calcium ions and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), are modulated (Komatsu et al., 2013; Rorsman and Ashcroft, 2018). Temporal changes in the concentration of these two molecules cause the secretory granules (compartments within the β-cells that store insulin) to fuse with the plasma membrane, thereby releasing insulin into the blood stream (Rorsman and Ashcroft, 2018; Figure 1).

Distinct pools of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) exist within individual β-cells.

cAMP and calcium ions (Ca2+) are important second messengers in cells. In the β-cells of the pancreas, they regulate the release of insulin (light blue) into the blood stream, . Tenner et al. found that the level of Ca2+ (blue line) oscillates uniformly across the cell. The level of cAMP (red line) in the cytosol oscillates in phase with the level of Ca2+, as does the level in free pools of cAMP in the plasma membrane (bottom right). However, the level in spatially constrained pools of cAMP in the plasma membrane (shown here in pink) oscillates out-of-phase with Ca2+ and cAMP in the cytosol in the plasmaand elswhere in the membrane.

In β-cells, the concentrations of calcium ions and cAMP oscillate to integrate external and internal signaling cues and encode them into parameters such as amplitude and frequency (Parekh, 2011; Schöfl et al., 1994). Depending on these parameters, different processes are elicited by the activity of second messengers. Previous research has shown that second messengers are not only controlled at various times, they are also spatially divided within the cells. So far, however, it remains unclear how the spatial organization of these highly diffusible molecules is achieved. Now, in eLife, Jin Zhang and colleagues from the University of California, San Diego – including Brian Tenner as first author – report new insights into second messenger oscillations (Tenner et al., 2020).

Tenner et al. used targeted biosensors to measure cAMP levels in various areas within β-cells. They identified different, spatially separated pools of cAMP, which were set apart by different oscillation patterns and concentrations of cAMP. More specifically, cAMP pools situated near specific protein complexes in the plasma membrane oscillate out-of-phase with cAMP pools located freely in the plasma membrane or in the cytosol. In comparison, calcium ion levels oscillated uniformly in the entire cell.

Using super resolution microscopy, the researchers found that the enzymes that produce and degrade cAMP play an important role in the oscillation process. The enzyme that synthesizes cAMP forms clusters in the plasma membrane, while the enzyme that degrades cAMP is dispersed in the cytosol. Based on these observations, Tenner et al. compiled a mathematical model, which confirmed that the different distributions of the two enzymes enables cAMP to form compartmentalized pools close to the plasma membrane clusters, where it is produced.

An enzyme known as protein kinase A further processes the signals encoded in the second messenger concentrations by helping calcium ions to enter the cell, thereby affecting calcium ion concentrations in the entire cell. Tenner et al. demonstrated that this effect of protein kinase A is dependent on the clustering of enzymes that produce cAMP: when these clusters were disrupted, the oscillations of calcium ions in the cytosol were less sustained and asynchronous. This suggests that modulating the oscillations of second messengers in distinct signaling compartments can affect communication in the entire cell.

While this work adds important new insights into oscillatory second messenger networks, it is based on observations made using an ammonium salt to stimulate a signaling responses. This pharmacological treatment might induce responses inside the cell that could differ from those observed after a physiological stimulation. In the future, it will be important to examine how the compartments of cAMP react to relevant physiological cues such as elevated blood sugar or blood fat levels. It will also be crucial to investigate whether the observed effects on calcium ions in the cell ultimately influence the production of insulin.

Nevertheless, Tenner et al. describe a new mechanism that may change how we think about cell signaling. Oscillatory second messenger networks integrate external and internal signals and are therefore crucial for cellular information processing. Amplitude and frequency of second messenger oscillations have long been established as parameters relevant for encoding informationIt is well known that the amplitude and frequency of these oscillations can encode information (Parekh, 2011; Schöfl et al., 1994). The findings of Tenner et al., however, suggest that the relative oscillatory phase of spatially discrete cAMP pools may constitute an additional mode for encoding information. In such a conceptual framework, a third mode of information processing would significantly increase the cell’s capability to integrate information and respond to changes in its environment (Waltermann and Klipp, 2011).

References

-

Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion: a newer perspectiveJournal of Diabetes Investigation 4:511–516.https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.12094

-

Decoding cytosolic Ca2+ oscillationsTrends in Biochemical Sciences 36:78–87.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2010.07.013

-

Pancreatic β-Cell electrical activity and insulin secretion: of mice and menPhysiological Reviews 98:117–214.https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00008.2017

-

Mechanisms of cellular information processingTrends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 5:53–59.https://doi.org/10.1016/1043-2760(94)90002-7

-

Information theory based approaches to cellular signalingBiochimica Et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 1810:924–932.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.07.009

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: November 17, 2020 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2020, Kuhn and Nadler

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,091

- Page views

-

- 100

- Downloads

-

- 1

- Citations

Article citation count generated by polling the highest count across the following sources: Crossref, PubMed Central, Scopus.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Biochemistry and Chemical Biology

- Plant Biology

Metabolism and biological functions of the nitrogen-rich compound guanidine have long been neglected. The discovery of four classes of guanidine-sensing riboswitches and two pathways for guanidine degradation in bacteria hint at widespread sources of unconjugated guanidine in nature. So far, only three enzymes from a narrow range of bacteria and fungi have been shown to produce guanidine, with the ethylene-forming enzyme (EFE) as the most prominent example. Here, we show that a related class of Fe2+- and 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases (2-ODD-C23) highly conserved among plants and algae catalyze the hydroxylation of homoarginine at the C6-position. Spontaneous decay of 6-hydroxyhomoarginine yields guanidine and 2-aminoadipate-6-semialdehyde. The latter can be reduced to pipecolate by pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase but more likely is oxidized to aminoadipate by aldehyde dehydrogenase ALDH7B in vivo. Arabidopsis has three 2-ODD-C23 isoforms, among which Din11 is unusual because it also accepted arginine as substrate, which was not the case for the other 2-ODD-C23 isoforms from Arabidopsis or other plants. In contrast to EFE, none of the three Arabidopsis enzymes produced ethylene. Guanidine contents were typically between 10 and 20 nmol*(g fresh weight)-1 in Arabidopsis but increased to 100 or 300 nmol*(g fresh weight)-1 after homoarginine feeding or treatment with Din11-inducing methyljasmonate, respectively. In 2-ODD-C23 triple mutants, the guanidine content was strongly reduced, whereas it increased in overexpression plants. We discuss the implications of the finding of widespread guanidine-producing enzymes in photosynthetic eukaryotes as a so far underestimated branch of the bio-geochemical nitrogen cycle and propose possible functions of natural guanidine production.

-

- Biochemistry and Chemical Biology

- Medicine

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is associated with higher fracture risk, despite normal or high bone mineral density. We reported that bone formation genes (SOST and RUNX2) and advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) were impaired in T2D. We investigated Wnt signaling regulation and its association with AGEs accumulation and bone strength in T2D from bone tissue of 15 T2D and 21 non-diabetic postmenopausal women undergoing hip arthroplasty. Bone histomorphometry revealed a trend of low mineralized volume in T2D (T2D 0.249% [0.156–0.366]) vs non-diabetic subjects 0.352% [0.269–0.454]; p=0.053, as well as reduced bone strength (T2D 21.60 MPa [13.46–30.10] vs non-diabetic subjects 76.24 MPa [26.81–132.9]; p=0.002). We also showed that gene expression of Wnt agonists LEF-1 (p=0.0136) and WNT10B (p=0.0302) were lower in T2D. Conversely, gene expression of WNT5A (p=0.0232), SOST (p<0.0001), and GSK3B (p=0.0456) were higher, while collagen (COL1A1) was lower in T2D (p=0.0482). AGEs content was associated with SOST and WNT5A (r=0.9231, p<0.0001; r=0.6751, p=0.0322), but inversely correlated with LEF-1 and COL1A1 (r=–0.7500, p=0.0255; r=–0.9762, p=0.0004). SOST was associated with glycemic control and disease duration (r=0.4846, p=0.0043; r=0.7107, p=0.00174), whereas WNT5A and GSK3B were only correlated with glycemic control (r=0.5589, p=0.0037; r=0.4901, p=0.0051). Finally, Young’s modulus was negatively correlated with SOST (r=−0.5675, p=0.0011), AXIN2 (r=−0.5523, p=0.0042), and SFRP5 (r=−0.4442, p=0.0437), while positively correlated with LEF-1 (r=0.4116, p=0.0295) and WNT10B (r=0.6697, p=0.0001). These findings suggest that Wnt signaling and AGEs could be the main determinants of bone fragility in T2D.