In Vivo Models: Visualizing traumatic brain injuries

Traumatic brain injuries are a leading cause of death and disability in younger people, as well as an important risk factor for neurodegenerative diseases and dementia in older adults. They can be caused by direct physical insults, whiplash or shockwaves such as those produced by explosions (Cruz-Haces et al., 2017). Yet traumatic events can also have effects beyond the immediate death and damage to neurons. In particular, they can disrupt a protein known as Tau, which normally maintains the stability of many neuronal cells. When this happens, an abnormal, hyperphosphorylated version of Tau accumulates in cells and spreads throughout the central nervous system by turning healthy Tau proteins into the harmful variant (Johnson et al., 2013; Ojo et al., 2016; Zanier et al., 2018). This accumulation is the hallmark of illnesses known as tauopathies, which include Alzheimer’s disease and a progressive brain condition found in athletes who experience regular head blows.

Scientists need accessible animal models in which they can easily observe and manipulate the proliferation of abnormal Tau proteins after a brain trauma. Rat and mouse models exist, but they are expensive and not well suited to visualizing what is happening inside the brain. Now, in eLife, Ted Allison (University of Alberta) and colleagues – including Hadeel Alyenbaawi (Alberta and Majmaah University) as first author and other researchers in Alberta and Pittsburgh – report new zebrafish larvae models for both tauopathies and traumatic brain injuries (Alyenbaawi et al., 2021).

The first model is formed of transgenic, ‘Tau-GFP reporter’ zebrafish in which the spread of the abnormal protein can be directly observed. To achieve this result, Alyenbaawi et al. genetically manipulated the animals so that their neurons would carry a reporter version of Tau that is fused with a green fluorescent protein (or GFP). As the larvae are transparent, their nervous system and the fluorescent Tau are easily visible. The fish were then injected with abnormal mice Tau proteins, causing the reporter Tau to aggregate into mobile ‘puncta’ – small dots which are a hallmark of tauopathies. More puncta were observed when extracts from brains with Tau-linked conditions were injected into the larvae, rather than the normal proteins.

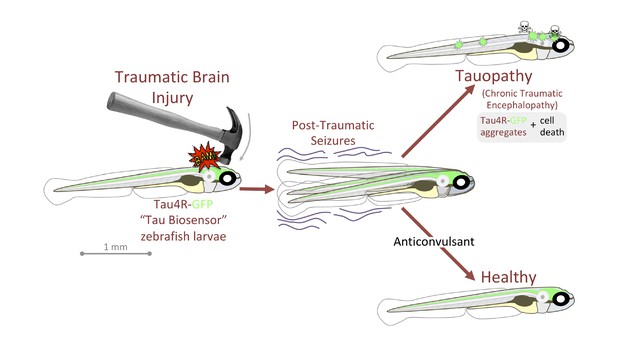

Alyenbaawi et al. also devised a simple and inexpensive zebrafish model for traumatic brain injury. They put the larvae inside a closed syringe, and dropped a weight onto the plunger, creating a shockwave to mimic blast injuries in humans. Three days in a row of this regimen creates conditions reminiscent of those faced in repetitive sports injury. In the Tau-GFP reporter larvae, the shockwave treatment led to fluorescent puncta in the brain and spinal cord, consistent with traumatic brain injuries leading to Tau pathologies (Figure 1). Similarly, past reports have shown that healthy mice developed a Tau-linked condition when they received brain extracts from conspecifics that experienced traumatic brain injuries (Zanier et al., 2018).

Traumatic brain injury results in seizures and Tau-linked conditions in zebrafish larvae.

Zebrafish larvae with neurons that carry Tau proteins fused with a fluorescent reporter (Tau4R-GFP) are subjected to a brain injury (left). Many then experience seizures, and without treatment they develop a Tau-linked condition in which the proteins aggregate and the neurons die (top right). Larvae that receive anticonvulsants are protected to a certain extent against seizures and the Tau-linked illness (bottom right).

Image credit: Figure based on figure 7 of Alyenbaawi et al., 2021 (CCBY 4.0).

In humans, epileptic seizures appear in over half of traumatic brain injury victims, and especially in those who have received a blast injury; these episodes may initiate or exacerbate the progression of Tau-linked conditions. In zebrafish, the traumatic brain injury larvae also developed seizure-like behaviors, with the intensity of the seizures being positively correlated to the spread of abnormal Tau. Drugs that promoted or stopped seizures respectively increased or decreased the extent of the Tau-linked condition, suggesting that anticonvulsants could help to manage brain traumas in the clinic (Figure 1).

Alyenbaawi et al. carefully identified the limitations of their models, observing for instance that the Tau-GFP reporter could spread in larvae even when the animals did not receive anomalous Tau proteins. This may result from relatively high levels of the Tau reporter in the transgenic animals, outlining the importance of controlling the expression levels of the transgene.

Apart for a recent model which used ultrasound, very few methods have been available so far to simulate traumatic brain injury in zebrafish (Cho et al., 2020). This was particularly the case for larvae, despite these young animals having a more easily observable central nervous system, a high throughput, and an ethical advantage compared to adults. The models developed by Alyenbaawi and colleagues thus constitute a welcome addition to understand the mechanisms associated with traumatic brain injury.

References

-

Pathological correlations between traumatic brain injury and chronic neurodegenerative diseasesTranslational Neurodegeneration 6:20.https://doi.org/10.1186/s40035-017-0088-2

-

Chronic repetitive mild traumatic brain injury results in reduced cerebral blood flow, axonal injury, gliosis, and increased T-Tau and tau oligomersJournal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology 75:636–655.https://doi.org/10.1093/jnen/nlw035

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: February 2, 2021 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2021, Ekker

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,252

- views

-

- 100

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Neuroscience

Mechanosensory neurons located across the body surface respond to tactile stimuli and elicit diverse behavioral responses, from relatively simple stimulus location-aimed movements to complex movement sequences. How mechanosensory neurons and their postsynaptic circuits influence such diverse behaviors remains unclear. We previously discovered that Drosophila perform a body location-prioritized grooming sequence when mechanosensory neurons at different locations on the head and body are simultaneously stimulated by dust (Hampel et al., 2017; Seeds et al., 2014). Here, we identify nearly all mechanosensory neurons on the Drosophila head that individually elicit aimed grooming of specific head locations, while collectively eliciting a whole head grooming sequence. Different tracing methods were used to reconstruct the projections of these neurons from different locations on the head to their distinct arborizations in the brain. This provides the first synaptic resolution somatotopic map of a head, and defines the parallel-projecting mechanosensory pathways that elicit head grooming.

-

- Neuroscience

Cortical folding is an important feature of primate brains that plays a crucial role in various cognitive and behavioral processes. Extensive research has revealed both similarities and differences in folding morphology and brain function among primates including macaque and human. The folding morphology is the basis of brain function, making cross-species studies on folding morphology important for understanding brain function and species evolution. However, prior studies on cross-species folding morphology mainly focused on partial regions of the cortex instead of the entire brain. Previously, our research defined a whole-brain landmark based on folding morphology: the gyral peak. It was found to exist stably across individuals and ages in both human and macaque brains. Shared and unique gyral peaks in human and macaque are identified in this study, and their similarities and differences in spatial distribution, anatomical morphology, and functional connectivity were also dicussed.