Viruses: What triggers inflammation in COVID-19?

It is almost two years since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). As of today, there have been more than 290 million confirmed cases and 5 million related deaths worldwide (Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, 2022). Although SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, including those that use mRNA, have been successfully rolled out in many countries, effective treatments for severe COVID-19 are still urgently needed.

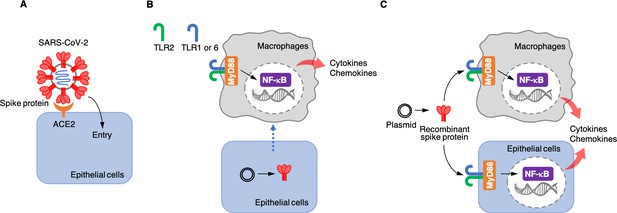

Each SARS-CoV-2 viral particle consists of a protein envelope that contains its single stranded RNA genome, which codes for four structural proteins: the spike, the membrane, the envelope, and the nucleocapsid (Yang and Rao, 2021). The spike protein binds to a receptor called angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on the surface of the human epithelial cells that line the lungs. This allows the virus to enter the cell and use the cell’s RNA and protein synthesis machinery to replicate itself (Figure 1A).

Roles of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein during infection and inflammation.

(A) The spike protein (red) binds to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2, orange) on the surface of epithelial cells, leading to the virus entering the cells. (B) Khan et al. artificially introduced a plasmid containing the DNA sequence for the spike protein to epithelial cells (bottom) which were cultured together with macrophages (top) in the laboratory. This caused the epithelial cells to make the spike protein, which triggered the macrophages to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. However, under these conditions, the spike protein was not detected in the culture medium, suggesting that the macrophages are somehow able to sense the protein either inside or on the surface of epithelial cells. This activation requires the spike protein to bind to Toll-like receptors (TLRs) that have formed dimers – either TLR2 with TLR1, or TLR2 with TLR6. Adaptor protein MyD88 then activates a transcription factor, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), which induces the transcription of pro-inflammatory molecules. (C) Khan et al. also used a plasmid to produce recombinant spike protein in the laboratory, and then applied these proteins to the medium in which macrophages and epithelial cells were growing. This showed that the spike protein can trigger both types of cells to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. This activation also required the TLR dimers and MyD88.

Once the body recognizes that these viral proteins are pathogenic, it activates various immune cells, including macrophages (Amarante-Mendes et al., 2018). These immune cells produce pro-inflammatory molecules called cytokines and chemokines, which usually help the body clear the viral infection. However, if their release is poorly regulated, this can lead to a cytokine storm which can severely damage the body’s tissues and organs (Fajgenbaum and June, 2020; Blanco-Melo et al., 2020). Understanding how SARS-CoV-2 proteins activate intense inflammatory responses at the molecular level is necessary to develop treatment strategies for severe COVID-19. Now, in eLife, Hasan Zaki and colleagues from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center – including Shahanshah Khan as first author – report that the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 causes potent inflammatory responses in macrophages and epithelial cells (Khan et al., 2021).

Khan et al. first studied whether any of the four structural proteins of SARS-CoV-2 could activate inflammatory responses in human macrophages. To do this, they first produced recombinant versions of the proteins in the laboratory, and then co-cultured each of the proteins with macrophages. Of the four proteins, only the spike protein triggered the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in a way that depended on dose and time.

Next, Khan et al. wanted to know whether epithelial cells, such as the ones that line the lung, can activate macrophages when they are infected with SARS-CoV-2. This is possible because the virus – when it infects epithelial cells – releases its RNA genome inside these cells, including the part that encodes for the spike protein. The cells may then start producing this protein and releasing it into the extracellular space or presenting it on their surface. To test whether the spike protein could activate inflammatory responses when it was expressed by epithelial cells, Khan et al. grew epithelial cells in the lab, introduced DNA coding for the spike protein into them, and co-cultured them with macrophages. The experiment showed that the macrophages produced pro-inflammatory cytokines (Figure 1B), but the spike protein was not found in the medium used to grow the cells. These results suggest that infected epithelial cells do not release the spike protein into the extracellular environment, and that macrophages instead somehow sense the spike proteins produced in epithelial cells through direct or physiochemical interactions.

Khan et al. then wanted to find out which part of the spike protein was responsible for the inflammatory response. The spike protein is divided into two functionally different domains: the S1 subunit, which binds to ACE2; and the S2 subunit, which helps the virus to enter epithelial cells. Khan et al. produced each of these subunits separately in the laboratory and co-cultured them with macrophages to determine which of the domains of the protein triggered the inflammatory response. They found that both subunits were able to activate macrophages to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in vitro. Khan et al. also co-cultured the two spike protein subunits with epithelial cells similar to those that line the lung, which resulted in the epithelial cells also producing pro-inflammatory molecules (Figure 1C).

Interestingly, both spike protein subunits failed to induce the expression of anti-viral proteins called type I interferons (interferon-1α and interferon-β), which are part of the body’s natural defense system against disease-causing agents. This is similar to what is seen in patients with severe COVID-19, who have high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, but low levels of type I interferons. To demonstrate that the inflammatory responses induced by the spike protein do not depend on ACE2 binding, Khan et al. used an ACE2 inhibitor. When the inhibitor was applied to cells that had been co-cultured with the spike protein, the cells still produced cytokines and chemokines.

Finally, Khan et al. tried to determine which receptors and associated signaling pathways were required for the inflammatory responses induced by the spike protein. Human cells have various receptor proteins on their surface that can recognize viral proteins and trigger downstream signaling pathways (Amarante-Mendes et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2021). A group of these receptors are called Toll-like receptors (TLRs). Khan et al. showed that, in order for macrophages and epithelial cells to recognize the spike protein, one of these receptors, called TLR2, needs to dimerize with TLR1 or TLR6. When the spike protein binds to one of these dimers, it activates the adaptor protein MyD88, which in turn activates nuclear factor κB, a transcription factor that regulates the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Figure 1C).

A recent study reported that expression of TLR2 and MyD88 was associated with COVID-19 disease severity (Zheng et al., 2021). This, combined with the results of Khan et al., suggests that TLR2 and its downstream signaling pathways may be good therapeutic targets for attenuating the cytokine storm and improving the survival of patients with COVID-19.

References

-

Pattern recognition receptors and the host cell death molecular machineryFrontiers in Immunology 9:2379.https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02379

-

Cytokine stormThe New England Journal of Medicine 383:2255–2273.https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra2026131

-

Structural biology of SARS-CoV-2 and implications for therapeutic developmentNature Reviews Microbiology 19:685–700.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-021-00630-8

-

Viral proteins recognized by different TLRsJournal of Medical Virology 93:6116–6123.https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.27265

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: January 20, 2022 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2022, Sawa and Akaike

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 5,224

- views

-

- 293

- downloads

-

- 6

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Chromosomes and Gene Expression

- Immunology and Inflammation

Ikaros is a transcriptional factor required for conventional T cell development, differentiation, and anergy. While the related factors Helios and Eos have defined roles in regulatory T cells (Treg), a role for Ikaros has not been established. To determine the function of Ikaros in the Treg lineage, we generated mice with Treg-specific deletion of the Ikaros gene (Ikzf1). We find that Ikaros cooperates with Foxp3 to establish a major portion of the Treg epigenome and transcriptome. Ikaros-deficient Treg exhibit Th1-like gene expression with abnormal production of IL-2, IFNg, TNFa, and factors involved in Wnt and Notch signaling. While Ikzf1-Treg-cko mice do not develop spontaneous autoimmunity, Ikaros-deficient Treg are unable to control conventional T cell-mediated immune pathology in response to TCR and inflammatory stimuli in models of IBD and organ transplantation. These studies establish Ikaros as a core factor required in Treg for tolerance and the control of inflammatory immune responses.

-

- Evolutionary Biology

- Immunology and Inflammation

CD4+ T cell activation is driven by five-module receptor complexes. The T cell receptor (TCR) is the receptor module that binds composite surfaces of peptide antigens embedded within MHCII molecules (pMHCII). It associates with three signaling modules (CD3γε, CD3δε, and CD3ζζ) to form TCR-CD3 complexes. CD4 is the coreceptor module. It reciprocally associates with TCR-CD3-pMHCII assemblies on the outside of a CD4+ T cells and with the Src kinase, LCK, on the inside. Previously, we reported that the CD4 transmembrane GGXXG and cytoplasmic juxtamembrane (C/F)CV+C motifs found in eutherian (placental mammal) CD4 have constituent residues that evolved under purifying selection (Lee et al., 2022). Expressing mutants of these motifs together in T cell hybridomas increased CD4-LCK association but reduced CD3ζ, ZAP70, and PLCγ1 phosphorylation levels, as well as IL-2 production, in response to agonist pMHCII. Because these mutants preferentially localized CD4-LCK pairs to non-raft membrane fractions, one explanation for our results was that they impaired proximal signaling by sequestering LCK away from TCR-CD3. An alternative hypothesis is that the mutations directly impacted signaling because the motifs normally play an LCK-independent role in signaling. The goal of this study was to discriminate between these possibilities. Using T cell hybridomas, our results indicate that: intracellular CD4-LCK interactions are not necessary for pMHCII-specific signal initiation; the GGXXG and (C/F)CV+C motifs are key determinants of CD4-mediated pMHCII-specific signal amplification; the GGXXG and (C/F)CV+C motifs exert their functions independently of direct CD4-LCK association. These data provide a mechanistic explanation for why residues within these motifs are under purifying selection in jawed vertebrates. The results are also important to consider for biomimetic engineering of synthetic receptors.