The Sec14-like phosphatidylinositol transfer proteins Sec14l3/SEC14L2 act as GTPase proteins to mediate Wnt/Ca2+ signaling

Abstract

The non-canonical Wnt/Ca2+ signaling pathway plays important roles in embryonic development, tissue formation and diseases. However, it is unclear how the Wnt ligand-stimulated, G protein-coupled receptor Frizzled activates phospholipases for calcium release. Here, we report that the zebrafish/human phosphatidylinositol transfer protein Sec14l3/SEC14L2 act as GTPase proteins to transduce Wnt signals from Frizzled to phospholipase C (PLC). Depletion of sec14l3 attenuates Wnt/Ca2+ responsive activity and causes convergent and extension (CE) defects in zebrafish embryos. Biochemical analyses in mammalian cells indicate that Sec14l3-GDP forms complex with Frizzled and Dishevelled; Wnt ligand binding of Frizzled induces translocation of Sec14l3 to the plasma membrane; and then Sec14l3-GTP binds to and activates phospholipase Cδ4a (Plcδ4a); subsequently, Plcδ4a initiates phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) signaling, ultimately stimulating calcium release. Furthermore, Plcδ4a can act as a GTPase-activating protein to accelerate the hydrolysis of Sec14l3-bound GTP to GDP. Our data provide a new insight into GTPase protein-coupled Wnt/Ca2+ signaling transduction.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.26362.001Introduction

Wnt ligands, a large family of secreted lipoglycoproteins, control a large number of developmental events in animals, including cell fate, migration and polarity, embryonic patterning, organogenesis and stem cell renewal (MacDonald et al., 2009; Clevers and Nusse, 2012). Mammals express 19 Wnt members that bind to a corresponding receptor among 10 Frizzled (Fz) receptors (Niehrs, 2012). These receptors have a seven transmembrane span motif characteristic of G protein-coupled receptors, and, following binding of a Wnt ligand, activate different downstream pathways (Semenov et al., 2007; Loh et al., 2016). In the canonical Wnt pathway, Wnt signaling stabilizes cytoplasmic β-catenin and thereby promotes its nucleus translocation and accumulation to activate downstream target genes transcription (MacDonald et al., 2009). Wnts also signal through at least two β-catenin-independent (non-canonical) branches, the Wnt/Planer Cell Polarity (PCP) and Wnt/Ca2+ pathways, during vertebrate development. They are both devoted to modulate cytoskeleton organization to coordinate or polarize cell convergent and extension movements (Veeman et al., 2003; Kühl et al., 2000b; Angers and Moon, 2009). In the Wnt/PCP pathway, the monomeric small GTPases such as RhoA and Rac1 are required for transducing Wnt-Fz signaling to c-Jun N-terminal Kinase (JNK) to direct cell polarity and cell movement (Huelsken and Birchmeier, 2001; Wodarz and Nusse, 1998).

The Wnt/Ca2+ signaling pathway emerged with the observations that overexpression of Xenopus Wnt5A and rat Fz2 in zebrafish embryos stimulated intracellular calcium flux and calcium-activated intracellular pathway (Kohn and Moon, 2005; Slusarski et al., 1997a, 1997b). It is demonstrated that pertussis toxin-sensitive heterotrimeric G protein subunits, e.g., Gαo and Gαt, are required for transducing the specific Wnt-Fz-Dishevelled complex signals downstream to activate phospholipase C (PLC) (Halleskog et al., 2012; Halleskog and Schulte, 2013; Liu et al., 1999). The activated PLC cleaves PIP2, a membrane-bound inositol lipid, into diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (InsP3). DAG stimulates protein kinase C (PKC) to induce ERK phosphorylation, while InsP3 binds to its corresponding receptor on the ER membrane, opening calcium channels for Ca2+ release and increasing cytoplasmic Ca2+ ion levels (Kadamur and Ross, 2013). Besides regulating cytoskeleton organization, Wnt/Ca2+ also can influence CE movements through modulating calcium-dependent cell adhesion or dynamics of calcium storage and release (Kühl et al., 2001; Slusarski and Pelegri, 2007; Tada and Heisenberg, 2012; Wallingford et al., 2002). However, until now the interplay between Fz and heterotrimeric G/GTPase proteins in the Wnt/Ca2+ signaling pathway is very controversial (Oner et al., 2013; Schulte and Bryja, 2007). Therefore, it remains mysterious and debated about how to orchestrate the upstream Wnt/Fz stimulation with downstream PLC/Ca2+ components.

In recent years, a number of Sec14-like proteins have been identified and characterized. It has been demonstrated that dysfunction of Sec14-like proteins would cause various human diseases, such as breast cancer, prostate cancer, ataxia, and retinal degeneration syndromes (Cockcroft, 2012). Sec14-like proteins belong to atypical class III phosphatidylinositol transfer proteins (PITPs) (Allen-Baume et al., 2002) and consist of the versatile Sec14 domain associated with a GTPase motif of uncertain biological function (Habermehl et al., 2005; Novoselov et al., 1996; Merkulova et al., 1999). PITPs can transfer phosphatidylinositol (PI) and phosphatidylcholine (PC) between membranes, exchanging PI for PC and vice versa, in order to maintain balanced membrane lipid levels upon consumption of phosphoinositides (Wiedemann and Cockcroft, 1998). Although it has been established that PITPs integrate the lipid metabolome with phosphoinositide signaling cascades intracellularly, only very few studies indicate that PITPs can respond to extracellular molecular cues to initiate intracellular signaling (Xie et al., 2005; Kauffmann-Zeh et al., 1995). So far, there is no evidence about the biological importance of the GTPase motif in the Sec14-like proteins, as well as the crosstalk between PITP family proteins and Wnt/Ca2+ signaling.

In this study, we investigated the role of the zebrafish Sec14l3 in embryonic development and the molecular mechanism of its action. We demonstrate that genetic depletion of maternal sec14l3 results in defects in embryonic convergent and extension (CE) movements by impairing Wnt/Ca2+ signaling. Biochemical and genetic data indicate that Sec14l3 can transduce, via its intrinsic GTPase activity, Wnt-Fz signaling to activate phospholipase C.

Results

Depletion of maternal sec14l3 impairs the gastrulation CE movements in zebrafish

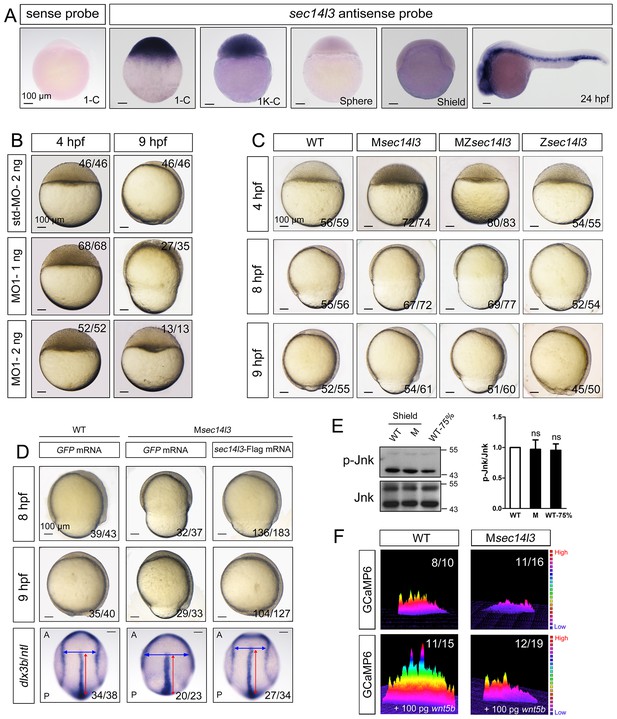

We are interested in roles of maternal genes in early development of zebrafish embryos. Our previous RNA-seq data suggested that, among three SEC14-like phosphatidylinositol transfer protein genes (sec14l1, sec14l2, and sec14l3), sec14l3 is highly expressed in zebrafish eggs. Whole mount in situ hybridization (WISH) confirmed the abundance of sec14l3 transcripts during cleavage and early blastula stages (Figure 1A). Thereafter, sec14l3 mRNA decreases to undetectable levels by the shield stage and increases again after the bud stage with enrichment in the vasculature cells (Figure 1A).

Sec14l3 depletion impairs CE movements and Wnt/Ca2+ signaling in zebrafish.

(A) Spatiotemporal expression pattern of sec14l3. Embryos were laterally viewed with animal pole to the top or with anterior to the left. Scale bars, 100 μm. (B) Morphological defects in sec14l3 morphants during gastrulation. Scale bars, 100 μm. (C) Morphological defects in Msec14l3, MZsec14l3 and Zsec14l3 mutants. Scale bars, 100 μm. (D) sec14l3 mRNA rescue assay. 150 pg sec14l3 mRNA was injected into Msec14l3 mutants for rescue, and then the morphology and dlx3b/ntl marker gene expression were examined. First two panels: lateral views; last panel: dorsal views. Blue and red two-way arrows indicate the width of neural plate and the length of notochord respectively. Scale bars, 100 μm. (E) Phosphorylation level of Jnk in Msec14l3 mutant embryos. p-Jnk (Thr183/Tyr185) and total Jnk were examined at the shield (Morphology comparable) and 75% epiboly stage (Time point comparable) by western blot. Quantification of relative protein levels is shown on the right, represented by mean ± SEM in three separate experiments (see also Figure 1—source data 1, ns, non-significant). (F) Differential induction of calcium transient activity in zebrafish embryos. Representative calcium release profiles of embryos at the sphere stage in wild-type and Msec14l3 mutant background with or without wnt5b mRNA overexpression. The color bar represents the number of transients: red represents high numbers, blue represents lower numbers, and the peaks represent more active regions. In all panels, the ratio in the right corner indicated the number of embryos with altered phenotypes/the total number of observed embryos.

-

Figure 1—source data 1

Numerical data for Figure 1E, Figure 1—figure supplement 1D and Figure 1—figure supplement 2B.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.26362.003

To study sec14l3 function, we first used two antisense morpholino oligonucleotides (MO), sec14l3-MO1 and sec14l3-MO2, which targeted different sequences around the 5’ untranslated region of sec14l3 mRNA, to block its translation (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A). Since sec14l3-MO1 was more effective than sec14l3-MO2 (Figure 1—figure supplement 1B), sec14l3-MO1 was used in subsequent experiments. Compared to standard MO (std-MO)-injected embryos, embryos injected with sec14l3-MO1 displayed slower epiboly in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1B).

To substantiate the knockdown effect, we generated four sec14l3 mutant lines by targeting the sequence around the translation start codon using transcriptional activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) technology (Figure 1—figure supplement 1C). The first line we obtained was sec14l3tsu-td10, which carried a 10 bp deletion (−3 to +7). Some zygotic mutants (Zsec14l3) of this line survived to adulthood, allowing production of maternal (Msec14l3) and maternal-zygotic mutants (MZsec14l3). In two-cell stage Msec14l3 or MZsec14l3 embryos, sec14l3 transcripts were almost eliminated (Figure 1—figure supplement 1D), which was likely due to unstable property of mutant mRNAs. Both Msec14l3 and MZsec14l3 mutant embryos showed a slower epibolic process, which mimicked sec14l3 morphants, whereas Zsec14l3 embryos appeared normal (Figure 1C). Therefore, the contribution of sec14l3 to gastrulation cell movements is a strictly maternal-effect. Interestingly, this maternal effect lasted through larval stages as evidenced by a reduced body length in Msec14l3 mutants compared with control embryos (Figure 1—figure supplement 1E). It appeared that cell proliferation and cell cycle progression in Msec14l3 mutant embryos were unaffected, then we focused on the event of cell movements (Figure 1—figure supplement 2A). At the bud stage (about 10 hpf), Msec14l3 mutant embryos had a broader and shorter embryonic axis, which was marked by the midline marker ntl and the neural plate border marker dlx3b (Figure 1D), indicative of impaired CE movements. Moreover, the defective CE movements of Msec14l3 embryos were not caused by cell adhesion defects between envelop cell layer (EVL) and deep cells (Figure 1—figure supplement 2B) and could be rescued by sec14l3 overexpression (Figure 1D). Maternal mutants of other sec14l3 lines (sec14l3tsu-td4, sec14l3tsu-td8 and sec14l3tsu-td9), which were obtained later on, also exhibited similar phenotypes. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that the maternal, but not the zygotic, contribution of sec14l3 is critical for normal epiboly and CE movements during gastrulation.

Sec14l3 is required for Wnt/Ca2+ signaling transduction

Since both Wnt/PCP and Wnt/Ca2+ can regulate cell movements during embryonic development (Cha et al., 2008; Niehrs, 2012; Lin et al., 2010; Webb and Miller, 2003), we then examined which pathway was affected in sec14l3 mutant embryos. Results showed that Wnt/PCP signaling readout, the phosphorylated Jnk, p-Jnk(Thr183/Tyr185), was almost unaffected in Msec14l3 mutant embryos, compared to wild-type embryos both at the same developmental stage and time point (Figure 1E). Human SEC14L2, rather than SEC14L3, is expressed in HEK293T and Wnt5-responsive PC3 cells, allowing easier examination of the effect of SEC14-like proteins on related signaling pathways (Figure 1—figure supplement 3A) (Ye et al., 2004). Like zebrafish sec14l3, knockdown of SEC14L2 in PC3 cells had little effect on p-JNK expression levels (Figure 1—figure supplement 3B and C). Therefore, we speculate that Sec14l3/SEC14L2 may not be crucial for the Wnt/PCP signaling pathway.

Next, we used the calcium indicator protein GCaMP6 to visualize calcium transients by confocal microscopy in zebrafish embryos, according to the method reported by Slusarski et al. (Chen et al., 2013; Nakai et al., 2001; Slusarski et al., 1997a). We found that the frequency of calcium release was attenuated obviously in Msec14l3 mutant embryos either at the basal level or upon Wnt5b stimulation (Figure 1F). We therefore conclude that maternal Sec14l3 plays a role in Wnt ligand-dependent calcium release during embryogenesis. Similarly, Wnt5a-induced calcium signal in PC3 cells was also decreased when SEC14L2 was knocked down by shRNA (Figure 1—figure supplement 3D). Thus, Sec14l3/SEC14L2 take part in Wnt/Ca2+ signaling transduction by promoting intracellular calcium release.

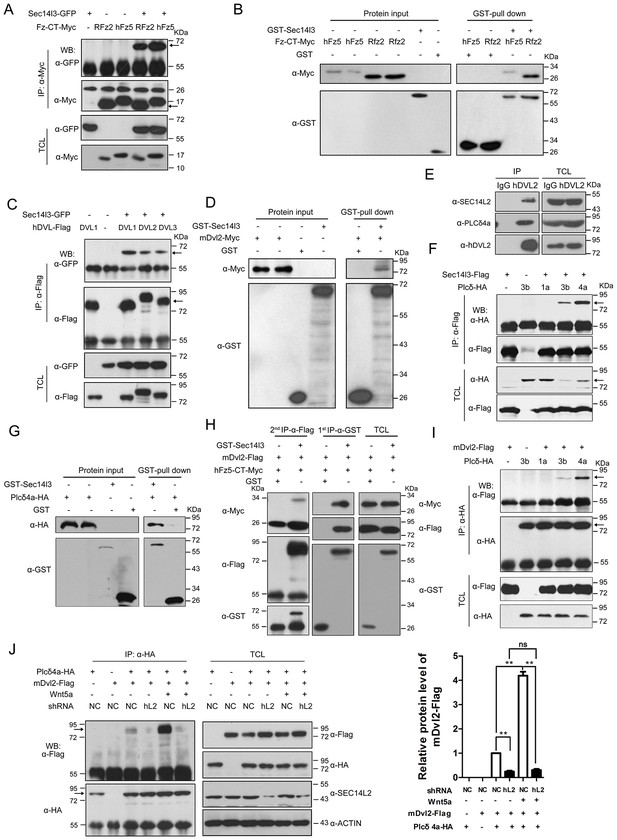

Sec14l3 forms complexes with Fz, Dvl and PLC

Fz, Dishevelled (Dvl) proteins and PLC are all implicated in Wnt-induced calcium release (Kühl et al., 2000a; Komiya and Habas, 2008), but the underlying mechanisms remain elusive. We wondered whether Sec14l3 could associate with these proteins and performed co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) in mammalian cells. We found that Sec14l3 associated with C-terminal of human Fz5 (hFz5-CT) and rat Fz2 (Rfz2-CT) in HEK293T cells (Figure 2A, Figure 2—figure supplement 1A). The in vitro-synthesized hFz5-CT and Rfz2-CT could be pulled down by GST-Sec14l3 (Figure 2B). These results support the idea that Sec14l3 directly interacts with Fz proteins. Our domain mapping analysis revealed that the N-terminal CARL-TRIO domain and the C-terminal GOLD domain of Sec14l3 were crucial for its interaction with RFz2-CT (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A–C).

Sec14l3 orchestrates complex formation among Fz, Dvl and PLC.

(A) Sec14l3 interacts with hFz5-CT and Rfz2-CT in HEK293T cells. IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, western blot; TCL, total cell lysates. The target protein in the precipitate was indicated by an arrow (same for other figures below). (B) Direct binding of Sec14l3 to hFz5-CT/Rfz2-CT in vitro. GST-Sec14l3 and hFz5-CT/Rfz2-CT-Myc were expressed in E. coli and purified. (C) Sec14l3 was detected in the protein complexes immunoprecipitated with Flag-tagged human DVL1/2/3 from HEK293T cells. (D) Direct binding of Sec14l3 to mDvl2 in vitro. GST-Sec14l3 and mDvl2-Myc were expressed in E. coli and purified. (E) Endogenous SEC14L2 and PLCδ4a interacts with DVL2 in MCF7 cells respectively. (F) Sec14l3 interacts with Plcδ3b and Plcδ4a in HEK293T cells. (G) Direct binding of Sec14l3 to PLCδ4a in vitro. GST-Sec14l3 and PLCδ4a-HA were expressed in E. coli and purified. (H) hFz5-CT, mDvl2 and Sec14l3 form a ternary complex in vitro. hFz5-CT-Myc and GST-Sec14l3 proteins purified from E. coli were incubated with mDvl2-Flag transfected cell lysates. The protein complexes were sequentially pulled down using GST (1 st IP-α-GST) and Flag antibody (2nd IP-α-Flag). Finally the second round immunoprecipitated proteins were detected using the corresponding antibodies. (I) mDvl2 interacts with Plcδ3b and Plcδ4a in HEK293T cells. (J) The interaction between mDvl2 and Plcδ4a is restrained in the stable SEC14L2 knockdown PC3 cells with or without 400 ng/μl Wnt5a stimulation. Quantification of relative mDvl2 levels from three independent experiments is shown as mean ± SEM on the right (see also Figure 2—source data 1, **p<0.01; ns, non-significant).

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Numerical data for relative protein level of mDvl2-Flag in Figure 2I.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.26362.008

Then, we tested physical interaction of Sec14l3 with different Dvl proteins. Co-IP results revealed that Sec14l3 physically interacted with human DVL1, DVL2 or DVL3 in HEK293T cells (Figure 2C). Used as a representative, Myc-tagged mDvl2 was determined to directly interact with GST-Sec14l3 (Figure 2D). And in MCF7 cells, endogenous SEC14L2 interacted with DVL2 (Figure 2E). In addition, this interaction was further validated in zebrafish embryos by overexpressing xDvl2-Myc and Flag-Sec14l3 mRNAs (Figure 2—figure supplement 1D). Deletion analysis showed that the Sec14l3’s Sec14 domain, but neither the CARL-TRIO nor GOLD domain, was essential for interaction with mDvl2 (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A,B and E). On the other hand, the DEP form of xDvl2, consisting of the DEP domain and the C-terminal region of xDvl2, was sufficient for the interaction with Sec14l3 (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A and F).

Next, we tested the physical interactions between zebrafish Sec14l3 and Plcδ family members, including Plcδ1a, Plcδ3b and Plcδ4a that are essential for PIP2 hydrolysis into DAG and InsP3. As shown in Figure 2F, immunoprecipitation of Flag-tagged Sec14l3 in HEK293T cells retrieved HA-tagged Plcδ4a and Plcδ3b, but not Plcδ1a. Furthermore, Plcδ4a-HA and GST-Sec14l3 fusion proteins were expressed in E.coli and purified for pull down assay, which showed a direct interaction between them (Figure 2G). Additionally, we also found their interaction in zebrafish embryos (Figure 2—figure supplement 1G). Domain mapping analysis revealed that the CARL-TRIO domain and the GOLD domain of Sec14l3, unlike the Sec14 domain, were crucial for interaction with the N2 region of Plcδ4a, including the PH and the EF hand domains (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A,B,H and I). Therefore, Sec14l3 utilizes different domains to interact with xDvl2 and Plcδ4a.

To test whether Sec14l3, Fz and Dvl form a complex, we performed two-step Co-IP experiment. Results showed that hFz5-CT-Myc was present in the GST-Sec14l3-Dvl2-Flag complex (Figure 2H), suggesting the presence of the hFz5/Dvl2/Sec14l3 ternary complexes. Furthermore, we found that mDvl2 was present in the Plcδ4a complexes, as well as in the Plcδ3b complexes, but absent in the Plcδ1a complexes (Figure 2I), which were similar to Sec14l3-Plcδ selective interactions (Figure 2F). DVL2 was also proved to interact with endogenous PLCδ4a in MCF7 cells (Figure 2E). Moreover, we found that different Wnt ligands stimulation could result in distinct calcium responses. Among of them, Wnt5a had a strong capacity to promote calcium release in PC3 cells (Figure 2—figure supplement 2A, and [Thrasivoulou et al., 2013]). Upon Wnt5a stimulation, mDvl2-Plcδ4a complex formation could be enhanced in PC3 cells, and knockdown of SEC14L2 led to a drastic reduction of mDvl2-Plcδ4a complexes (Figure 2J), indicating the presence of the mDvl2/Sec14l3/Plcδ4a ternary complexes.

Interestingly, Sec14l3-GFP could be co-immunoprecipitated with Sec14l3-Flag through its CARL-TRIO domain and GOLD domain (Figure 2—figure supplement 2B and C), suggesting oligomerization of Sec14l3. It is possible that Sec14-like protein oligomers may facilitate the formation of complexes with Fz, Dvl and Plcδ proteins.

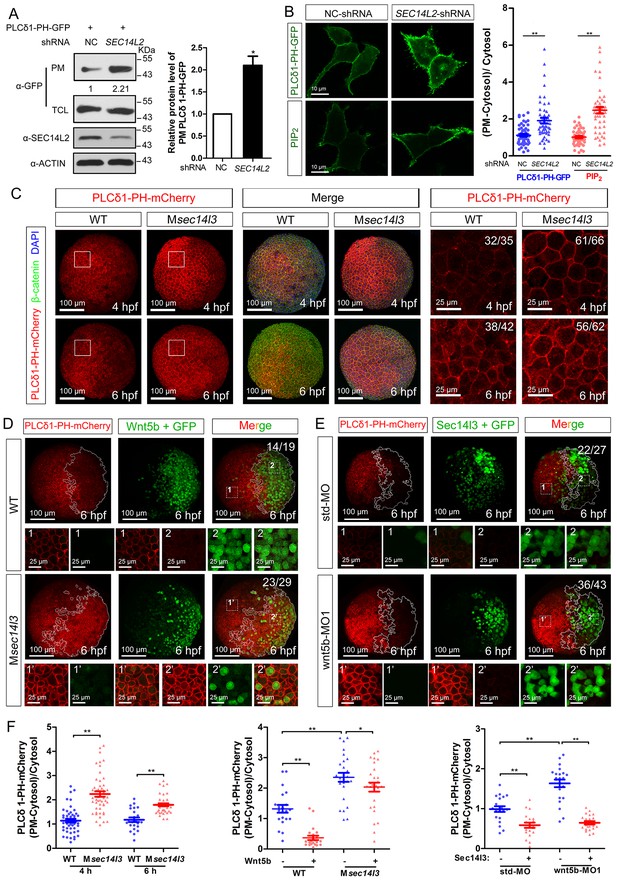

Sec14l3 is required for PLC-catalyzed hydrolysis of PIP2

Sec14-like proteins are members of PITP and assumed to transfer phosphoinositides (PIs) to the plasma membrane (PM) (Nile et al., 2010; Kearns et al., 1998; Wiedemann and Cockcroft, 1998; Wirtz, 1991). To test whether human SEC14L2 and zebrafish Sec14l3 have an effect on PI derivatives accumulation at the PM, we first measured levels of PIP2 in HEK293T cells, the lipid substrate of PLC, using a PH probe, which consists of a GFP-tagged PH domain from PLCδ1 that specifically binds to PIP2 (Várnai and Balla, 1998; Idevall-Hagren and De Camilli, 2015). If the PI transfer activity of SEC14L2 is blocked, the PIP2 level at the PM should be reduced. However, compared to control cells, transfection of PLCδ1-PH-GFP DNA into HEK293T cells depleted of SEC14L2 resulted in more PLCδ1-PH-GFP protein in the PM fraction (Figure 3A), indicative of more PIP2 at the PM. Confocal imaging also revealed that the PLCδ1-PH-GFP fluorescence at the PM was about 2-fold brighter in SEC14L2 shRNA stable cells than in the control cells (Figure 3B, top panel), which was consistent with changes of PIP2 levels detected using a PIP2 antibody (Figure 3B, lower panel). These results indicate that SEC14L2 may be required for PIP2 hydrolysis rather than for PIP2 transfer.

Sec14l3 facilitates PLC-catalyzed PIP2 hydrolysis induced by Wnt5b.

(A) PM isolation analysis of PM PIP2 levels using PLCδ1-PH-GFP as probe in HEK293T cells. Quantification data from three independent experiments are shown as mean ± SEM (see also Figure 3—source data 1, *p<0.05). (B) Immunofluorescence of PLCδ1-PH-GFP in first panel (transfected with PLCδ1-PH-GFP) and endogenous PIP2 in second panel shows PIP2 accumulation in the PM of stable SEC14L2-knockdown HEK293T cells. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (see also Figure 3—source data 1, **p<0.01; n ≥ 50 cells from three separate experiments). Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Immunofluorescence of PLCδ1-PH-mCherry (red, PIP2 probe), β-catenin (green, PM marker) and DAPI (blue, nucleus marker) shows PIP2 accumulation in the PM of Msec14l3 mutant cells. The first two whole embryo panels are 3D views of z-stacks (n = 30 for 4 hpf, n = 34 for 6 hpf), while the last panel is enlarged views of single z-stack pictures (z = 8 for 4 hpf, z = 7 for 6 hpf) from regions encompassed by white boxes. Scale bars, 100 μm for whole embryos; 25 μm for the enlarged columns. (D) Sec14l3 depletion compromises Wnt5b-induced degradation of PM PIP2. Immunofluorescence of PLCδ1-PH-mCherry (red) and GFP (green, indicating Wnt5b-expressed cells) is shown. Mosaic expression of 100 pg wnt5b mRNA was created in embryos with even distribution of PLCδ1-PH-mCherry mRNA. White polygons outline GFP expressed cells and single z-stack pictures (z = 10) from numbered regions in the whole embryo panels (3D view of z-stacks) are enlarged. Scale bars, 100 μm for whole embryos; 25 μm for the enlarged panels. (E) sec14l3 overexpression inhibits accumulation of PIP2 in wnt5b morphant embryos. Mosaic expression of sec14l3 by injecting 150 pg mRNA was created in embryos with even distribution of PLCδ1-PH-mCherry mRNA in std-MO or wnt5b-MO injected embryos. Single z-stack pictures (z = 11) from numbered regions in the whole embryo panels (3D view of z-stacks) are enlarged. (F) PM PIP2 quantification of (C–E) by calculating intensity of (PM-Cytosol)/Cytosol PLCδ1-PH-mCherry. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. (see also Figure 3—source data 1, **p<0.01; *p<0.05; ns, non-significant; n ≥ 50 cells from 10 embryos in three independent experiments).

-

Figure 3—source data 1

Numerical data for Figure 3A,B,F and Figure 3—figure supplements 1C–E and 2E.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.26362.012

Then, we switched to detect PIP2 in zebrafish embryos by injecting PLCδ1-PH-GFP mRNA. Compared to wild-type embryos, the Msec14l3 mutant and sec14l3 morphant embryos accumulated more PLCδ1-PH-GFP/PIP2 at the PM both at 4 and 6 hpf (Figure 3C and F, Figure 3—figure supplement 1A and C). With regard to PIP3, the metabolic product of PIP2, we also observed a similar PM elevation, indicated by AKT1-PH-mCherry probe, in Msec14l3 mutants or morphants (Figure 3—figure supplement 1B and C). Therefore, consistent with SEC14L2 in mammalian cells, depletion of Sec14l3 leads to the PIP2 accumulation at the PM likely due to inefficient activation of PLC but not deficiency of its PI transfer activity.

PLC-catalyzed hydrolysis of PIP2 produces InsP3 and DAG, two important secondary messengers in cell signaling transduction. InsP3 signals release calcium from intracellular stores, while DAG induces PKC-mediated ERK phosphorylation (Seitz et al., 2014). In conjunction with measuring calcium levels (Figure 1F), we also measured phosphorylation of ERK (p-ERK) in vitro and in vivo. As expected, SEC14L2 knockdown in HEK293T cells caused a reduction of p-ERK (Thr202/Tyr204), but had no effect on phosphorylated AKT (p-AKT Ser473) (Figure 3—figure supplement 1D). Similarly, both western blots and immunostaining of zebrafish embryos showed a significant decrease in p-Erk, but not p-Akt in Msec14l3 mutants (Figure 3—figure supplement 1E–G). Collectively, these data establish a role for Sec14l3 in regulation of PLC catalytic activity.

Wnt/Dvl-induced PLC activation is dependent on Sec14l3

To investigate whether Sec14l3 mediates Wnt5b/Dvl2-induced PLC transduction in vivo, PIP2 probe mRNA was injected into blastomeres at the 1 cell stage to visualize PIP2, which was followed by injection of a cocktail of wnt5b and GFP mRNA into one cell at the 16–32 cell stage to produce mosaic expression of Wnt5b. While injection of GFP mRNA alone has no effect on the PIP2 distribution (Figure 3—figure supplement 2A and E), PIP2 at the PM in the region with ectopic Wnt5b was significantly reduced compared to in the region without ectopic Wnt5b in the same wild-type embryos (Figure 3D, upper panels and Figure 3F), suggesting that Wnt5b stimulates PLC-catalyzed PIP2 hydrolysis. However, Wnt5b-dependent PLC activation was obviously inhibited in Msec14l3 mutant embryos, as evidenced by a much minor reduction in the PIP2 level (Figure 3D, lower panels and Figure 3F). Like Sec14l3 depletion, wnt5b morphant embryos accumulated more PLCδ1-PH-GFP/PIP2 at the PM both at 4 and 6 hpf, compared to std-MO injected embryos (Figure 3—figure supplement 2B and E). More importantly, wnt5b-MO-induced PM accumulation of PLCδ1-PH-GFP/PIP2 and CE defects could be individually restored by mosaic and 1 cell stage injection of sec14l3 mRNA (Figure 3E,F and Figure 3—figure supplement 2C). Taken together, these epistatic analyses indicate that Sec14l3 can transduce Wnt5 signal to activate PLC in embryos.

Next, we used a truncated form of Xenopus Dishevelled, xDsh-DelN, to stimulate PLC-catalyzed PIP2. xDsh-DelN is a N-terminal DIX domain deletion form that is sufficient to activate the Wnt/PCP and Wnt/Ca2+ but not Wnt/β-catenin pathways (Sheldahl et al., 2003). As expected, xDsh-DelN mosaic overexpression also lowered PIP2 levels at the PM in injected clonal region of wild-type embryos (Figure 3—figure supplement 2D, upper panels and 2E), while the xDsh-DelN- dependent PLC activation was also inhibited in Msec14l3 mutant embryos (Figure 3—figure supplement 2D, lower panels and Figure 3—figure supplement 2E). Therefore, it is speculated that Sec14l3 might mediate PLC activation downstream of Wnt5b/Dvl2 stimulation.

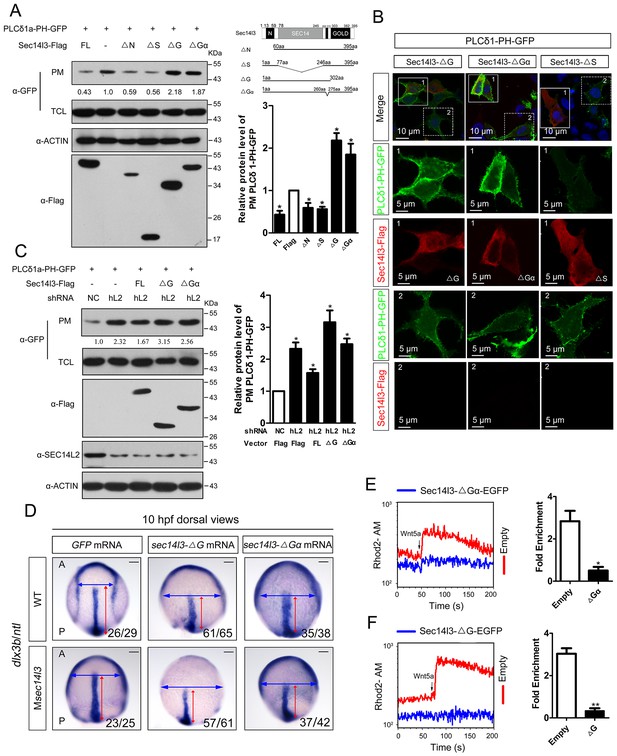

The GOLD and the Gα domains of Sec14l3 are crucial for activating Plcδ activity

To determine which Sec14l3 domain(s) is/are critical for PLC activation, several truncated forms of Sec14l3 were combined with a PIP2 probe for transfection in HEK293T cells. PM isolation assays showed that the truncated forms of CARL-TRIO domain (ΔN) and Sec14 domain (ΔS) still acted similarly to full-length Sec14l3, where a reduction was observed in the amount of PIP2 at the PM (Figure 4A). However, rather than leading to PIP2 degradation, forms of Sec14l3 lacking the GOLD domain (ΔG) or Gα subunit (ΔGα) induced PIP2 accumulation at the PM, suggesting that these forms are functioning as dominant negatives (Figure 4A). Similar results were observed with immunostaining (Figure 4B). To further evaluate this phenotype, we overexpressed the truncated forms of Sec14l3 in human SEC14L2 knockdown stable cells, and found that enrichment of PIP2 in the PM due to SEC14L2 depletion was partially compromised by transfecting the full-length form of zebrafish Sec14l3, but not ΔG or ΔGα forms (Figure 4C).

Sec14l3 activates PLC dependent on its GOLD and Gα domains.

(A) Analysis of PIP2 levels in the membrane. Different forms of Sec14l3 (right corner) were co-transfected with PLCδ1-PH-GFP into HEK293T cells, and PIP2-bound PLCδ1-PH-GFP in the PM was detected by Western blot. The relative levels of PLCδ1-PH-GFP in the PM were quantified and presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments on the right (*p<0.05). (B) Immunofluorescence of PLCδ1-PH-GFP (green, PIP2 probe) in HEK293T transfected with Sec14l3-ΔG, Sec14l3-ΔGα or Sec14l3-ΔS (red) respectively. Regions in white box are enlarged. Scale bar, 10 μm for the first panel and 5 μm for the enlarged panels. (C) PIP2 accumulation in stable SEC14L2-knockdown cells was not abolished by overexpression of Sec14l3-ΔG or Sec14l3-ΔGα. Statistical data from three independent experiments are presented as mean ± SEM on the right (*p<0.05). (D) CE defects in embryos with ΔG and ΔGα Sec14l3 overexpression. dlx3b/ntl marker gene expression were examined at 10 hpf after sec14l3-ΔG and sec14l3-ΔGα mRNA injection respectively. Scale bar, 100 μm. (E–F) Flow cytometry of Wnt5a-induced calcium signals in PC3 cells transfected with Sec14l3-ΔGα or Sec14l3-ΔG (blue curves). Left panel shows the kinetic calcium influx over a time course. Right panel shows fold enrichment of calcium influx after Wnt5a stimulation. Data from three independent experiments are presented as mean ± SEM (*p<0.05, **p<0.01). Blue and red curves indicate the transfected and control group respectively. All numerical data represented as a graph in the figure are shown in Figure 4—source data 1.

-

Figure 4—source data 1

Numerical data for relative protein level of PLCδ1-PH-GFP or phosphorylation level ratio in Figure 4 and Figure 4—figure supplement 1.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.26362.016

In consistent with the above biochemical data, overexpression of ΔG or ΔGα mRNA in wild-type embryos led to a broader and shorter embryonic axis. And, neither the morphological epiboly defects nor marker gene-labeled CE defects seen in Msec14l3 mutant embryos were rescued by either of these two truncated mRNAs (Figure 4D). Moreover, we found that ΔG or ΔGα form overexpression caused a significant reduction of p-Erk in wild-type embryos (Figure 4—figure supplement 1A and B) and a much lower calcium responsiveness in PC3 cells (Figure 4E and F, Figure 4—figure supplement 1C), which were quite similar to what happened in sec14l3 deficient situation (Figure 1F). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that the GOLD domain and the Gα subunit domain of Sec14l3 are required for activating Plcδ activity.

Sec14l3 promotes PM translocation and hydrolytic activity of Plcδ4a in response to Wnt5a stimulation

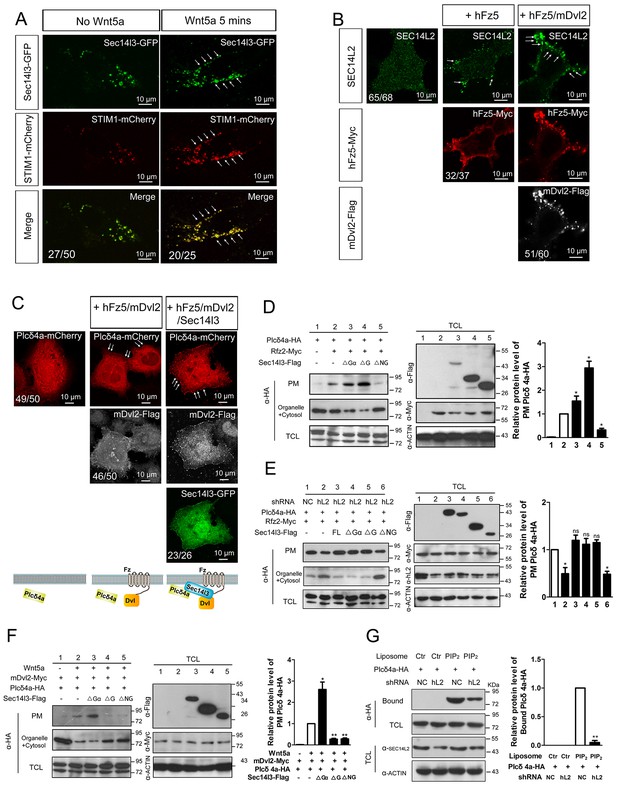

To further study the mechanism by which Sec14l3-mediated Wnt/PLC activation, we determined whether Sec14l3 translocated to the plasma membrane upon Wnt stimulation. As shown in Figure 5A, Figure 5—figure supplement 1A, Wnt5a stimulation induced a rapid translocation of Sec14l3-GFP to the PM, which was similar to the calcium sensor protein STIM1 (Liou et al., 2005) and enhanced by co-transfection of Dvl2. To rule out the possibility that Wnt5a-induced Sec14l3 PM recruitment might be a mere consequence of the calcium release, we tested the effect of hFz5/mDvl2 stimulation on Sec14 protein location in HEK293T and MCF7 cells that do not respond to hFz5/mDvl2 for calcium release (Mikels and Nusse, 2006; Foldynová-Trantírková et al., 2010). In HEK293T cells, endogenous SEC14L2 protein was enriched in the PM by hFz5 transfection, which was further enhanced by hFz5/mDvl2 coexpression (Figure 5B). Similar phenomenon was observed in MCF7 cells (Figure 5—figure supplement 1B). Additionally, we demonstrated that SEC14L2 knockdown had no effect on hFz5-mDvl2 interaction (Figure 5—figure supplement 1C), which suggests Fz-Dvl interaction might be independent of Sec14-like proteins. Therefore, combining the above data with pairwise biochemical interactions among Sec14l3, Fz and Dvl (Figure 2, Figure 2—figure supplement 1), we propose that Sec14l3 is a component of the Fz/Dvl/Sec14l3 complex, and its PM recruitment is promoted directly by Fz/Dvl in response to Wnt signaling stimulation.

PM zone enriched-Sec14l3 recruits PLC for activation upon Wnt5/Fz stimulation.

(A) Co-localization of Sec14l3 (green) with STIM1 proteins (red) in PC3 cells with or without Wnt5a stimulation. Arrows indicates PM-localized protein after Wnt5a stimulation. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Immunofluorescence of endogenous SEC14L2 in HEK293T cells with or without hFz5/mDvl2 transfection. Arrows indicates PM-localized SEC14L2 (green). Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Immunofluorescence of Plcδ4a-mCherry (red), mDvl2-Flag (gray) and Sec14l3-GFP (green) in MCF7 cells. PM-localized Plcδ4a (red) are indicated by arrows. The bottom panel show the schematic representation of transfected constructs in corresponding rows and an interpretation of the results. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) The Sec14l3 CARL-TRIO and GOLD domains are important for Rfz2 mediated Plcδ4a recruitment to the PM in the HEK293T cells. Statistical data from three independent experiments are presented as mean ± SEM on the right (*p<0.05; ns, non-significant; same for other statistical data below). (E) Rfz2-mediated Plcδ4a PM recruitment is abolished in stable SEC14L2-knockdown HEK293T cells and failed to be restored by Sec14l3-ΔNG overexpression. Statistical data are presented. (F) The Sec14l3 GOLD domain is important for Wnt5a mediated Plcδ4a recruitment to the PM in PC3 cells. Statistical data are presented. (G) SEC14L2 depletion perturbs Plcδ4a access to PIP2. Equal amounts of purified Plcδ4a protein and liposomes with or without PIP2 were incubated with control or SEC14L2 depleted cell lysates. Statistical data are presented. All numerical data represented as a graph in the figure are shown in Figure 5—source data 1.

-

Figure 5—source data 1

Numerical data for graphs in Figure 5 and Figure 5—figure supplement 1.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.26362.019

Then we hoped to know how Sec14l3 regulates PLC activity. PLC has been proposed to serve as a membrane attachment enzyme, which hydrolyzes many substrates such as PIP2 without dissociating from the lipid surface (Rhee, 2001). Therefore, we speculated that Sec14l3 might be necessary for recruitment of Plcδ4a to the PM for executing function. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the subcellular localization of Plcδ4a upon overexpression of Sec14l3. Immunostaining results in MCF7 cells showed that Sec14l3 actually promoted the PM localization of Plcδ4a after co-transfection with hFz5 and mDvl2 (Figure 5C). To determine which Sec14l3 domain(s) is/are critical for PLC recruitment, PM isolation assay was performed. In contrast to the cytoplasmic enrichment of Plcδ4a in rest cells, there was a substantial enrichment of Plcδ4a in the PM upon transfection with hFz5 or Rfz2 or both, which was enhanced by co-transfection with ΔGα or ΔG forms of Sec14l3, but not with ΔNG form (Figure 5D, Figure 5—figure supplement 1D). Furthermore, we found that Rfz2-induced enrichment of Plcδ4a at the PM was inhibited in SEC14L2 knockdown cells, which could be restored by overexpressing the full-length, ΔGα or ΔG form, but not ΔNG form, of Sec14l3 (Figure 5E). Therefore, we speculate that both the TRIO-CARL domain and GOLD domain are required for recruiting Plcδ4a to the PM upon Wnt receptors stimulation. Particularly, different from the receptors stimulation, ΔG form is sufficient to block Wnt5a-induced Plcδ4a PM recruitment in PC3 cells, indicating a more important function of the C-terminal GOLD domain of the protein (Figure 5F), which is consistent with the functional analysis of PIP2 localization (Figure 4A). Taken together, although Wnt5a ligand and its Fz receptors trigger Dvl2/Sec14l3-dependent Plcδ4a PM recruitment in a slightly different way, possibly due to the diverse functions of the C-terminal GOLD2 domain upon ligand stimulation, Sec14l3 is important for the PM translocation of Plcδ4a, which is mainly mediated by the C-terminal GOLD domain rather than the Gα subunit domain.

The next question is whether Sec14-like protein-mediated PM translocation promotes Plcδ4a binding to PIP2. To address this issue, we performed liposome binding assay. As shown in Figure 5G, interaction between purified Plcδ4a protein and liposome-bound PIP2 was detected following incubation with HEK293T control cell lysate; however, this interaction was significantly weakened when the SEC14L2 knockdown cell lysate was used. This result indicates that Plcδ4a accesses PIP2 in a Sec14l3-dependent manner.

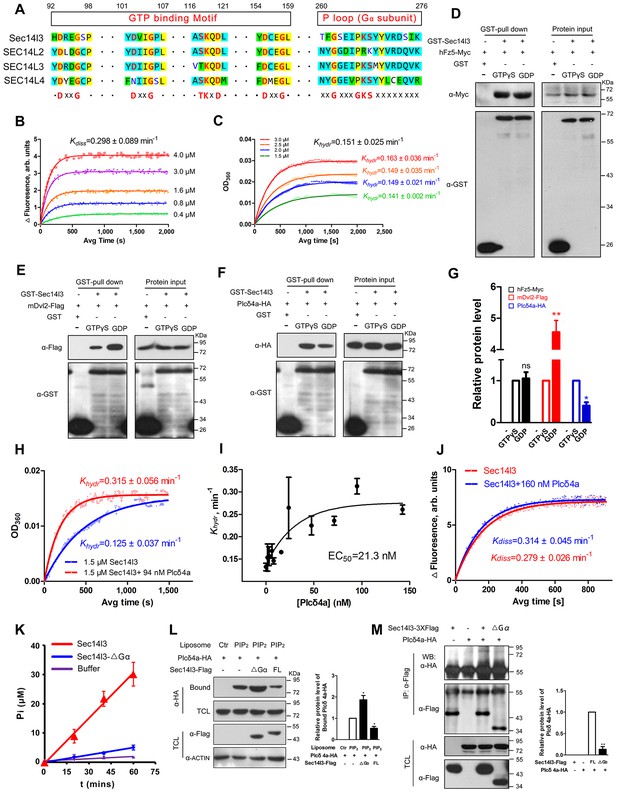

Sec14l3 functions as a GTPase protein in Wnt/PLC activation

We noticed that, although Sec14l3-ΔGα acts as a dominant negative form (Figure 4A–C), it works differently with ΔNG or ΔG form in mechanism, based on Plcδ4a PM recruitment results (Figure 5D–F, Figure 5—figure supplement 1D). As previously reported, human SEC14-like proteins contain a proposed Gα subunit and possess considerable GTPase activity (Habermehl et al., 2005; Novoselov et al., 1996; Merkulova et al., 1999; Novoselov et al., 1994). We wondered whether zebrafish Sec14l3 has the same property. The high sequence homology in the GTP binding motif and P loop region between zebrafish Sec14l3 and human SEC14L2/SEC14L3/SEC14L4 (Figure 6A) suggests a GTPase activity of zebrafish Sec14l3. Then we adopted BODIPY-FL-GTPγS conventional assay and MESG-based single-turnover assay to detect the GTP binding and GTP hydrolysis activities of Sec14l3 (Lin et al., 2014; McEwen et al., 2001; Tõntson et al., 2012; Webb, 1992). It estimated the Kdiss and Khydr rate constants for Sec14l3 to be 0.298 ± 0.089 min−1 and 0.151 ± 0.025 min−1 respectively (Figure 6B–C). These results indicated that Sec14l3 is a genuine GTPase protein with GTP binding and hydrolysis activities.

Sec14l3 exerts its GTPase activity to prime PLC.

(A) Protein sequence alignment of zebrafish Sec14l3, and human SEC14L2, SEC14L3, and SEC14L4 in GTP binding motif and P loop region (Gα subunit). Critical amino acids are highlighted in red as consensus at the last panel. (B) GTP binding activity of Sec14l3. The fluorescence of BODIPY-FL-GTPγS at indicated concentrations was measured at room temperature (λex = 490 nm and λem = 510 nm), following the addition of 10 μM Sec14l3. Data are representative uptake curves. The Kdiss constant of Sec14l3 from three independent experiments is 0.298 ± 0.089 min−1. (C) GTP hydrolysis activity of Sec14l3. Time-course of Pi release from Sec14l3-GTP at indicated concentrations measured by absorbance at 360 nm in the single-turnover assay based on MESG system. Data are representative GTP hydrolysis curves and the Khydr constant of Sec14l3 from three independent experiments is 0.151 ± 0.025 min−1. (D) Full-length hFz5 equally binds to GDP- and GTPγS-bound Sec14l3 in vitro. (E) Full-length mDvl2 binds preferentially to inactive GDP-bound Sec14l3 in vitro. (F) Purified Plcδ4a binds preferentially to active GTPγS-bound Sec14l3 in vitro. (G) Quantification of relative protein level of hFz5-Myc (D), mDvl2-Flag (E) or Plcδ4a-HA (F) bound by GST-Sec14l3 in the GTPγS/GDP form. Data are shown as mean ± SEM from three separate experiments (**p<0.01; p<0.05; ns, non-significant). (H) Plcδ4a functions as the GAP of Sec14l3. Data are representative GTP hydrolysis curves from three independent experiments. The Khydr constant is statistically significant between two treatments with p<0.05. (I) Quantification of the Khydr constants over different concentrations of Plcδ4a. Each concentration is plotted as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. (J) GTP binding activity of 10 μM Sec14l3 in the absence or presence of 160 nM Plcδ4a. Data shows an example of BODIPY-GTPγS uptake curve of three experiments. These two Kdiss constants have no significant difference by the Student’s t test. (K) Gα subunit deletion led to a decreased GTPase activity of Sec14l3. Data shown are representative curves out of three replicates and are plotted as mean ± SEM. (L) Sec14l3-ΔGα protein overexpression disturbs Plcδ4a-mediated PIP2 degradation in vitro. Equal amounts of purified Plcδ4a protein and liposomes containing PIP2 or not were incubated with Sec14l3-transfected cell lysates. Liposome-bound Plcδ4a was eluted and analyzed with quantification data as mean ± SEM on the right (*p<0.05). (M) Gα subunit mediates Plcδ4a interaction with Sec14l3 in HEK293T cells. Quantification data from three independent experiments are shown as mean ± SEM on the right (**p<0.01). All numerical data represented as a graph in the figure are shown in Figure 6—source data 1.

-

Figure 6—source data 1

Numerical data for graphs in Figure 6 and Figure 6—figure supplement 1.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.26362.022

A hallmark of G proteins is their ability to undergo conformational switches, from the GDP-bound ‘off’ state to the GTP-bound ‘on’ state and vice versa (Flock et al., 2015; Vetter and Wittinghofer, 2001). To gain full insights into the dynamic switch between Sec14l3 forms, we examined the binding affinity of its interacting proteins with GTPγS/GDP-loaded Sec14l3 in vitro. Results indicated that hFz5 had no preference for GDP- or GTPγS-bound Sec14l3, while Dvl2 preferred binding to GDP-bound Sec14l3 (Figure 6D,E and G). On the contrary, Plcδ4a showed much stronger interaction with GTPγS-bound form (Figure 6F–G). These observations suggest that Dvl2 might participate in the switch of Sec14l3-GDP to Sec14l3-GTP, which then binds to and activates PLC.

Another important question is how active Sec14l3-GTP is cycled back to inactive Sec14l3-GDP. We speculated that Plcδ4a, a binding partner of Sec14l3-GTP, might act as the GTPase-activating protein (GAP). To test this hypothesis, we compared the GTP hydrolysis activity of Sec14l3 in the presence and absence of Plcδ4a protein. Results showed that the Khydr rate was increased about 2.5-fold to 0.315 ± 0.056 min−1 in the presence of 94 nM Plcδ4a, showing the GAP activity of Plcδ4a (Figure 6H). Additionally, quantification of the Khydr constants over different concentrations of Plcδ4a determined its EC50 value (50% of maximal effect value) as 21.3 nM (Figure 6I). On the other hand, our data disclosed that Plcδ4a is incapable of stimulating GTP uptake by Sec14l3 (Figure 6J). Therefore, Plcδ4a acts not only as a Sec14l3-GTP effector but as a terminator, a GAP of Sec14l3-GTP.

To verify the importance of the Gα domain for the GTPase activity, full-length Sec14l3 and Sec14l3-ΔGα were purified from E. coli, and resuspended for steady-state GTPase activity assay. Results showed that full-length Sec14l3 stimulated the hydrolysis of GTP in a dose-dependent manner (data not shown), while Sec14l3-ΔGα exhibited the relatively low GTPase activity (Figure 6K), indicating the Gα subunit actually engenders the GTPase activity of Sec14l3. Moreover, incubation with lysates from cells transfected with ΔGα form led to much higher levels of Plcδ4a-PIP2 association compared to the full-length form of Sec14l3 (Figure 6L); Gα domain deletion had no effect on interaction with hFz5-CT, but impaired its binding to mDvl2 and Plcδ4a (Figure 6M and Figure 6—figure supplement 1A and B). We speculate that the GTPase activity deficient Sec14l3-ΔGα is unable to bridge Dvl2 and Plcδ4a for complex formation so that Plcδ4a-bound PIP2 may not be hydrolyzed due to PLC autoinhibition (Hicks et al., 2008).

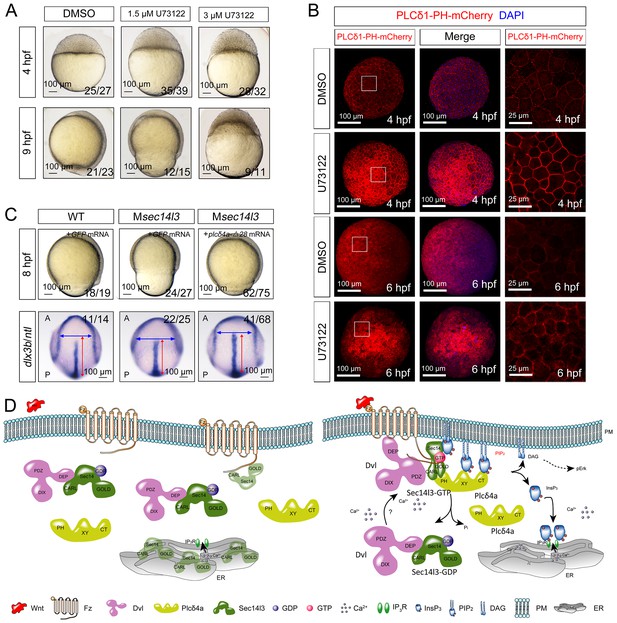

Upregulation of PLC activity rescued sec14l3 deficiency-induced CE defects in embryos

To confirm that attenuated PLC/Ca2+ signaling was responsible for the phenotypes in Msec14l3 mutant embryos, we used U73122, an inhibitor of PLC (Ashworth et al., 2007), to test whether PLC inhibition phenocopies Msec14l3 mutants. Compared to the DMSO control, U73122 (1.5 μM or 3 μM) treatment at the 1 cell stage indeed postponed embryonic epiboly process, phenocoping Msec14l3 mutants (Figure 7A). Additionally, U73122 treatment caused a significant enhancement of PIP2 accumulation at the PM at 4 and 6 hpf (Figure 7B), which phenocopied Msec14l3 mutants.

Sustained PLC activity partially rescues Msec14l3 defects.

(A) Morphological defects in zebrafish embryos treated with 1.5 μM or 3 μM U73122 from the 1 cell stage. DMSO treated group serves as a control. Scale bars, 100 μm. (B) Confocal imaging of PLCδ1-PH-mCherry (red, PIP2 probe) shows the PM accumulation of PIP2 in zebrafish embryos treated with 1.5 μM DMSO or 1.5 μM U73122 at 4 and 6 hpf. The first two whole embryo panels are 3D views of z-stacks, while the last panel is enlarged views of single z-stack pictures (z = 5 for both 4 hpf and 6 hpf) from regions encompassed by white boxes. Scale bars, 100 μm for the whole embryos; 25 μm for the enlarged columns. (C) Active Plcδ4a overcomes the CE defects in Msec14l3 mutants. 100 pg plcδ4a-Δ28 mRNA was used for injection. Lateral views for embryos in the first panel, dorsal views for those in the last panel. Blue and red two-way arrows indicate the width of neural plate and the length of notochord respectively. Scale bars, 100 μm. (D) Hypothetic working model of Sec14l3 participation in Wnt/Ca2+ signaling. In the absence of Wnt (left panel), Sec14l3 is mainly maintained in the ER and cytoplasm, forming a heterodimer with Dvl in its inactive state, Sec14l3-GDP. Upon Wnt5 stimulation (right panel), Fz/Dvl-mediated Sec14l3 is recruited to the PM and switched to the active state, Sec14l3-GTP, and subsequently promotes Plcδ4a localization from cytoplasm to the PM and then the consequent activity at least in two aspects: its PIP2 hydrolytic activity to generate second messenger InsP3 and DAG for signaling propagation (Ca2+ release and p-Erk activation); and its GAP activity to terminate Sec14l3-GTP.

We explored a possibility to rescue Msec14l3 mutant phenotype by artificially activating PLC in mutants. We constructed an X/Y linker-truncated form of Plcδ4a, Plcδ4a-Δ28, which was assumed to enhance the basal activity by relieving its autoinhibition (Hicks et al., 2008). Injection of plcδ4a-Δ28 mRNA into Msec14l3 mutant embryos partially rescued defects in morphology and CE marker gene expression (Figure 7C). So it is very likely that Plcδ4a plays a role in gastrulation cell movements by mediating Sec14l3 effect in the Wnt/Ca2+ signaling pathway.

Discussion

To date, only a few biochemical studies based on overexpression or inhibitors of proteins have suggested the implication of heterotrimeric G proteins in Wnt/Ca2+ signaling (Malbon, 2004; Katanaev et al., 2005; Schulte and Bryja, 2007). However, it is unresolved as to how Fz/Dvl couples with G/GTPase proteins in Wnt/Ca2+ signaling (Sheldahl et al., 1999; Aznar et al., 2015; Schulte and Bryja, 2007). In this study, we show that Sec14-like phosphatidylinositol transfer proteins can function as GTPase proteins in Wnt/Ca2+ signaling. As modeled for Sec14l3 (Figure 7D), Sec14l3-GDP can form complexes with Fz and Dvl; in respond to non-canonical Wnt stimulation, activated Sec14l3-GTP associates with and activates PLC at the PM, and promotes PLC-mediated PIP2 hydrolysis to generate second messengers that propagate the Wnt/Ca2+ signaling cascade. In zebrafish, depletion of maternal sec14l3 impairs Wnt/Ca2+ signaling transduction and consequently causes defective gastrulation cell movements. Our findings not only reveal a critical function for Sec14l3 in regulating Wnt/Ca2+ signaling, but provide a comprehensive view of mechanisms about GTPase proteins involvement during the signaling transduction, breaking the argument whether the 7-TM Fz can directly bind to and activate G proteins. We propose it is the GTPase proteins, Sec14l3/SEC14L2, other than the classical heterotrimeric G proteins, that can simultaneously bind to upstream Fz/Dvl and activate downstream PLC for signal propagation. Therefore, the function of Sec14-like proteins is not limited to regulate the exchange of membrane lipids.

The direct Fz-Sec14l3 interaction can also be interpreted as Sec14l3-mediated regulation at the receptor level, such as Fz internalization or recycling in Wnt/Ca2+ signaling (data not shown), which needs to be further investigated. Although our clues so far can’t discriminate the transducer as a trimer or multimer, the organizer function of Sec14l3 in Wnt/Ca2+ is recognizable. What’s more, it has been suggested that lipid transfer proteins may not simply function as diffusible vehicles mediating lipid transfer between membranes, but also devices of assigning PI lipids to various enzymatic reactions in a strictly regulated biological context (Mousley et al., 2012). Our findings disclose multifaceted functions of lipid transfer proteins such as Sec14l3 and fill an important gap in our understanding of how Wnt/Fz/Dvl transduce the signal to PLC for Ca2+ release.

Although Sec14l3 is initially identified as a member of PITP, its depletion does not cause PIP2 or PIP3 reduction at the PM both in zebrafish embryos and mammalian cells. Our studies demonstrate that the depletion of Sec14l3 leads to PIP2 accumulation at the PM due to inefficient activation of PLC. However, we cannot exclude the possibility of the involvement of Sec14l3 PI transfer activity in embryonic development because other PITP family members, such as Sestd1 and Sec14l1, are also highly expressed in zebrafish embryos (data not shown). Therefore, to investigate the intrinsic transfer activity of Sec14l3 during early embryogenesis, genetic analysis of double or triple mutants is necessary.

One of the most important aspects of our work is the discovery that the GTPase activity of Sec14l3 is critical for Plcδ4a activation. We find that Plcδ4a binds to Sec14l3-GTP with apparently higher affinity and functions as a Sec14l3-GAP protein. However, Sec14l3-GEF proteins remain unknown. Wnt receptor Fz is a kind of G protein-coupled receptors, which can act as GEF proteins for their cognate G proteins upon binding of a ligand (Malbon, 2004; Schulte and Bryja, 2007; Dijksterhuis et al., 2014). We doubt that hFz5 or Rfz2 functions as the Sec14l3-GEF protein, because these Fz proteins show similar binding affinity towards GDP- or GTP-bound Sec14l3 and cannot accelerate the GTP uptake by Sec14l3 (Figure 6D,G and Figure 6—figure supplement 1C). Considering that Fz receptors can activate Gαi proteins and enhance Wnt/PCP signaling via the Dvl-binding protein, Daple, a novel non-receptor GEF (Aznar et al., 2015; Ishida-Takagishi et al., 2012), and Dvl2 does prefer to bind toward Sec14l3-GDP rather than Sec14l3-GTP in our hand (Figure 6E and G), we tend to believe that Dvl2 serves as a scaffolding protein to recruit an unknown Sec14l3-GEF, thereby enhancing Sec14l3-GTP formation. As for which is the particular GEF for Sec14l3 in Wnt/Ca2+ signaling transduction, more studies are needed. Besides, with the aid of available configuration-specific Sec14l3-GTP antibody in the future, it will be of great interest to figure out the conformational switches in vivo.

In summary, this study sheds light on a unique feature of the Sec14l3 protein. Through its intrinsic GTPase activity, it is capable of tightly coupling phospholipase activation with the proximity of PLC to its substrate. Moreover, these findings also provide the mechanism by which Dvl promotes calcium signaling.

Materials and methods

Embryos, injection and TALEN mutants generation

Request a detailed protocolsec14l3 TALEN mutants were generated in the Tg(flk:EGFP;gata1:dsRed) (PRID:ZFIN_ZDB_FISH_150901_14755; ZFIN_ZDB_ALT_051223_6) transgenic fish using the FastTALE TALEN Assembly Kit (SiDanSai, Shanghai, China). The target site was near the start codon and included 22 bp both upstream and downstream (Figure 1—figure supplement 1C). To identify the candidate fishes with mutated alleles, genomic DNA was extracted from the tail and amplified using primer pairs as follows: the forward primer 5’-ccagcggcggagataaatc-3’ and the reverse primer 5’-acatctatgacagacagcaatg-3’. The amplicons were purified for sequencing to determine the mutation types or digested with NlaIII to distinguish wild type and mutant embryos. The progenies derived from crosses between secl14l3 heterozygotes were raised to adulthood, and homozygous mutant males and females were identified by genotyping. MZsec14l3 or Msec14l3 mutant embryos were obtained by crossing homozygous mutant females to homozygous mutant males or wild-type males, respectively; Zsec14l3 mutant embryos were obtained by crossing heterozygous females to heterozygous males. Fishes were handled according to the institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) protocol (AP#13-MAM1), which was approved and permitted by the Tsinghua University Animal Care and Use Committee. Embryos were staged according to Kimmel et al. (1995).

Constructs

Request a detailed protocolZebrafish sec14l3 and human SEC14L2 full coding sequences were amplified using the following primers: sec14l3 with 5’-CCGGAATTCATGAGCGGAAGGGTTGGAGATC-3’ (forward) and 5’-CCGCTCGAGCTAGTTGTCTGATTGGTTGAC-3’ (reverse), and SEC14L2 with 5’-CCGGAATTCATGAGCGGCAGAGTCGGCGATC-3’ (forward) and 5’-CCGCTCGAGTTATTTCGGGGTGCCTGCC-3’ (reverse). For information on the other constructs used in this study, please refer to the Supplementary file 1.

mRNAs, morpholinos, and microinjection mRNAs were synthesized from corresponding linearized plasmids in vitro using a mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and purified with RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Duesseldorf, German). Morpholinos were synthesized by Gene Tools, LLC. The sequences of MOs used in our study are as follows: sec14l3-MO1, 5’-TCAGATCTCCAACCCTTCCGCTCAT-3’; sec14l3-MO2, 5’-ATGTCGCCACGAGTGCAGCAGAAAT-3’; wnt5b-MO1, 5’-GTCCTTGGTTCATTCTCACATCCAT-3’; and std-MO, 5’-CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA-3’. About 1–1.5 nl of mRNA (or morpholino solution) was injected into the yolk at the 1 cell stage for ubiquitous expression or into one single cell at the 16–32 cell stage for clonal expression using the typical MPPI-2 quantitative injection equipment (Applied Scientific Instrumentation Co., Eugene, OR). The injection dose was the amount of the mRNA or morpholino received by a single embryo.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization and immunofluorescence

Request a detailed protocolWhole-mount in situ hybridization was performed essentially following a standard protocol. Digoxigenin-UTP-labeled antisense RNA probes for detecting dlx3b and ntl mRNA were generated in vitro using a linearized plasmid (Huang et al., 2007). Following in situ hybridization, the embryos were immersed in glycerol and photographed using the Ds-Ri1 CCD camera under a Nikon SMZ1500 stereoscope. Embryonic immunofluorescence was carried out as previously described (Zhang et al., 2012), and the following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-p-Erk (Thr202/Tyr204) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, #9101, RRID:AB_331646), rabbit anti-p-Akt (Ser473) (Cell Signaling Technology, #4060, RRID:AB_2315049), mouse anti-SEC14L2 (ORIGENE, Rockville, MD, TA503723, RRID:AB_11126641), phalloidin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, p1951, RRID:AB_2315148). Immunostained embryos were imaged under Nikon A1RMPSi lasers scanning confocal microscope using z-stack devices with 3.5 μm interval. And whole embryo images are 3D views of z-stacks, while the magnified images are pictures of a single z plane snap.

Cell culture, transfection and stable cell line establishment

Request a detailed protocolHEK293T cells (RRID:CVCL_0063) were cultured in DMEM (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT) and 50 μg/ml penicillin/streptomycin (PS) (Invitrogen). PC3 cells (RRID:CVCL_0035) were cultured in F12K with 10% FBS and 50 μg/ml PS. All cell lines were obtained from the Cell Resource Center, Peking Union Medical College (which is the headquarters of National Infrastructure of Cell Line Resource, NSTI). Cell lines were checked for free of mycoplasma contamination by PCR and culture. Its species origin was confirmed with PCR. The identity of the cell line was authenticated with STR profiling (FBI, CODIS). All the results can be viewed on the website (http://cellresource.cn). Transfections were performed using the polyethylenimine method. To establish human SEC14L2 knockdown stable cell line, negative control shRNA (SHC016) and SEC14L2 shRNA (TRCN0000019589, TRCN0000019590) plasmids (ordered from Sigma) were transfected into HEK293T/PC3 cells and then transfected cells were selected with puromycin (1 μg/ml). Following removal of the puromycin, the cells were allowed to recover and expand in regular growth medium and then were screened by protein immunoblotting. For serum starvation, cells were incubated in culture media in the absence of any additional supplements for 16 hr.

Imaging of calcium levels in embryos and cytosolic calcium measurements by flow cytometry

Request a detailed protocolTo image calcium levels in embryos, pXT7-GCaMP6 plasmid was constructed based on pGP-CMV-GCaMP6 and linearized for GCaMP6 mRNA labelling. Then GCaMP6 mRNA was mixed with Rhodamine and injected into 1 cell stage embryos, which were embed in low-melting agar at the indicated stages for time lapse imaging. Then the resulting images were treated to generate pseudocolor ratio images as previously described (Slusarski et al., 1997b, 1997a).

For calcium measurements in PC3 cells, cells were transfected with indicated plasmids for three days and loaded with calcium dye Quest Fluo 8-AM (AAT Bioquest, Sunnyvale, CA, 21083) or Rhod2-AM (AAT 21064) before flow cytometry analysis. During analysis, baseline fluorescence was measured for 50 s and stopped for Wnt5a addition, then measurement was resumed immediately for a total of 200s.

Western Blot, co-immunoprecipitations, immunostaining and GST pull-downs

Request a detailed protocolWestern blots, co-IPs and immunostaining were performed as previously described (Zhang et al., 2009). For two-step of Co-IPs, the first step Co-IP components were eluted with the reduced glutathione for the second step immunoprecipitation experiments. Staining of PIP2 in the PM was carried out according to a protocol previously published by Hammond et al. (2009). Fluorescent images were acquired using a Nikon A1RMPsi lasers scanning confocal microscope. The following commercial antibodies were used in this study: anti-Flag (F1804, Sigma, RRID:AB_262044), anti-HA (sc-7392, Santa Cruz, Dalls, TX, RRID:AB_627809), anti-Myc (sc-40AC, Santa Cruz, RRID:AB_627268), anti-GFP (sc-9996, Santa Cruz, RRID:AB_627695) and anti-hDVL2 (#3216, CST, RRID:AB_2093338). Wnt3a (5036-WN), Wnt5a (645-WN) and Wnt11 (6179-WN) ligands were purchased from R&D (Minneapolis, MN). For GST pull-down assay, GST-Plcδ4a-HA and GST-Sec14l3 fusion proteins were expressed in E.coli and purified using glutathione-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare, Marlborough, MA). After washing with PBS, GST-Plcδ4a-HA beads were incubated with PreScission Protease (GE Healthcare) to remove the GST tag and the resulting Plcδ4a-HA was harvested by PBS elution. The GST-Sec14l3 beads were washed with PBS and then incubated with the purified Plcδ4a-HA fusion protein for 2 hr at 4°C, and then washed with PBS again. The final eluent was analyzed by western blot using anti-GST and anti-HA antibodies. For GTPγS/GDP-Sec14l3 pull down assay, immobilized GST-Sec14l3 protein (on glutathione-Sepharose beads) was prepared and incubated with binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 100 mM NaCl, 0.4% [vol:vol] Nonidet P-40, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EDTA, 30 μM GTPγS /GDP, 2 mM DTT, protease inhibitor mixture) for 90 mins at room temperature as described before (Wu et al., 1993; Aznar et al., 2015). Then lysates of HEK293T cells with hFz5-Myc or mDvl2-Flag plasmid transfection or purified Plcδ4a-HA (5 μg) protein were added and rotated at 4°C for another 2 hr. Beads were then washed using wash buffer (4.3 mM Na2HPO4, 1.4 mM KH2PO4 [pH 7.4], 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 0.1% [vol:vol] Tween 20, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EDTA, 30 μM GTPγS /GDP, 2 mM DTT) for 4 times every 3 min, finally boiled in 2xloading buffer for SDS-PAGE using corresponding antibodies.

Liposome binding and membrane isolation assays

Request a detailed protocolFor the liposome binding assay, 1 μg HA-tagged Plcδ4a protein purified from E. coli, 20 μl 1 mM PolyPIPosomes (Echelon Biosciences, Salt Lake City, UT, Y-0000 and Y-P045), none or 5% PIP2, 500 μl cell lysates transfected with control shRNA or SEC14L2 shRNA and 500 μl binding buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% NonidetP-40) were mixed and rotated for 4 hr at 4°C and then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. The liposome pellet was then washed with 1 ml of binding buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% NonidetP-40) for three times. The bound and flow-through samples were eluted in 2xSDS loading buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and then Plcδ4a levels were measured by immunoblot with anti-HA antibody.

For the membrane isolation assay, a MinuteTM Plasma Membrane Protein Isolation Kit (Invent Biotechnologies, Inc., Plymouth, MN, Catalog number: SM-005) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The isolated membrane samples were then dissolved in 2xSDS loading buffer and detected by separated by western blot using appropriate antibodies.

GTP binding and hydrolysis assays

Request a detailed protocolGTP binding and hydrolysis activity are measured using BODIPY-FL-GTPγS conventional assay and MESG-based single-turnover assay respectively; BODIPY-FL-GTPγS conventional assay is based on the release of the fluorescence quenching of BODIPY-FL-GTPγS (a non-hydrolyzable GTP analog) upon its binding to G proteins. BODIPY-FL-GTPγS (Invitrogen, G22183) binding to recombinant Sec14l3 was determined in 10 mM HEPEs (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA and 10 mM MgCl2 (HEM buffer). The fluorescence (λex = 490 nm and λem = 510 nm) was monitored for samples at different concentrations of BODIPY-FL-GTPγS, following the addition of 10 μM Sec14l3 protein, in a fluorescence microplate reader (Thermo Scientific VARIOSKAN FLASH). For the kinetic experiments, fluorescence of BODIPY-FL-GTPγS alone was measured in HEM at room temperature for 3 min and then binding was initiated with addition of excess Sec14l3. The change in fluorescence was measured over time and fitted with one phase exponential equation: a*(1-e-kt) to obtain the Kdiss constant using GraphPad Prism 5.

The hydrolysis of GTP by Sec14l3 was measured by the MESG system monitoring the time course absorbance at 360 nm. The reaction was determined in 100 μl solution containing 50 mM MOPs (pH 7.0), 1 mM EDTA, 200 mM GTP, 1 U/ml purine nucleoside phosphorylase, 0.2 mM MESG and the recombinant Sec14l3 protein (reconstituted in Tris-HCl buffer). Single-turnover GTPase reactions were initiated by adding of MgCl2 to a final concentration of 5 mM using the injector unit followed by immediate measurement (Thermo Scientific VARIOSKAN FLASH). The hydrolysis data fitted with one phase exponential equation: a*(1-e-kt) to obtain the Khydr constant using GraphPad Prism 5. The time-course of Pi release from Sec14l3-GTP at four different concentrations was monitored, and finally averaged to determine the Khydr constant of Sec14l3.

For measurements of Plcδ4a GAP functions, indicated amounts of GAP proteins were mixed with Sec14l3 before MgCl2 initiation, and control experiments with indicated GAP proteins were carried out to provide a background of absorbance in each independent measurement to be subtracted from the sample signals.

Steady-state GTPase activity was performed using a QuantiChrom ATPase/GTPase Assay kit (GENTAUR, San Jose, CA, DATG-200) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Request a detailed protocolQuantitative data are presented as mean ± SEM, and comparisons were performed between groups using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. For all analyses, *p<0.05; **p<0.01 were considered statistically significant; ns indicated statistical non-significance with p>0.05. Each experiment was carried out at least three times independently.

References

-

Proximal events in wnt signal transductionNature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 10:468–477.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm2717

-

Molecular and functional characterization of inositol trisphosphate receptors during early zebrafish developmentJournal of Biological Chemistry 282:13984–13993.https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M700940200

-

The diverse functions of phosphatidylinositol transfer proteinsCurrent Topics in Microbiology and Immunology 362:185–208.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5025-8_9

-

WNT/Frizzled signalling: receptor-ligand selectivity with focus on FZD-G protein signalling and its physiological relevance: iuphar Review 3British Journal of Pharmacology 171:1195–1209.https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.12364

-

Recombinant SEC14-like proteins (TAP) possess GTPase activityBiochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 326:254–259.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.021

-

General and versatile autoinhibition of PLC isozymesMolecular Cell 31:383–394.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.018

-

New aspects of Wnt signaling pathways in higher vertebratesCurrent Opinion in Genetics & Development 11:547–553.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-437X(00)00231-8

-

Detection and manipulation of phosphoinositidesBiochimica Et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 1851:736–745.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.12.008

-

Mammalian phospholipase CAnnual Review of Physiology 75:127–154.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183750

-

Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafishDevelopmental Dynamics 203:253–310.https://doi.org/10.1002/aja.1002030302

-

Wnt5b-Ryk pathway provides directional signals to regulate gastrulation movementThe Journal of Cell Biology 190:263–278.https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.200912128

-

Frizzleds: new members of the superfamily of G-protein-coupled receptorsFrontiers in Bioscience 9:1048–1058.https://doi.org/10.2741/1308

-

Fluorescent BODIPY-GTP analogs: real-time measurement of nucleotide binding to G proteinsAnalytical Biochemistry 291:109–117.https://doi.org/10.1006/abio.2001.5011

-

A high signal-to-noise ca(2+) probe composed of a single green fluorescent proteinNature Biotechnology 19:137–141.https://doi.org/10.1038/84397

-

The complex world of WNT receptor signallingNature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 13:767–779.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm3470

-

Mammalian diseases of phosphatidylinositol transfer proteins and their homologsClinical Lipidology 5:867–897.https://doi.org/10.2217/clp.10.67

-

Regulation of the G-protein regulatory-Gαi signaling complex by nonreceptor guanine nucleotide exchange factorsJournal of Biological Chemistry 288:3003–3015.https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.418467

-

Regulation of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase CAnnual Review of Biochemistry 70:281–312.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.281

-

The frizzled family of unconventional G-protein-coupled receptorsTrends in Pharmacological Sciences 28:518–525.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2007.09.001

-

Dishevelled activates Ca2+ flux, PKC, and CamKII in vertebrate embryosThe Journal of Cell Biology 161:769–777.https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.200211094

-

Modulation of embryonic intracellular Ca2+ signaling by Wnt-5ADevelopmental Biology 182:114–120.https://doi.org/10.1006/dbio.1996.8463

-

Calcium signaling in vertebrate embryonic patterning and morphogenesisDevelopmental Biology 307:1–13.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.04.043

-

Characterization of heterotrimeric nucleotide-depleted Gα(i)-proteins by Bodipy-FL-GTPγS fluorescence anisotropyArchives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 524:93–98.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2012.05.017

-

Calcium signalling during embryonic developmentNature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 4:539–551.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm1149

-

The role of phosphatidylinositol transfer proteins (PITPs) in intracellular signallingTrends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 9:324–328.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1043-2760(98)00080-0

-

Phospholipid transfer proteinsAnnual Review of Biochemistry 60:73–99.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.bi.60.070191.000445

-

Mechanisms of Wnt signaling in developmentAnnual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 14:59–88.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.59

-

Identification of critical regions on phospholipase C-beta 1 required for activation by G-proteinsThe Journal of Biological Chemistry 268:3704–3709.

-

Rock2 controls TGFbeta signaling and inhibits mesoderm induction in zebrafish embryosJournal of Cell Science 122:2197–2207.https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.040659

Article and author information

Author details

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (31522035)

- Shunji Jia

National Natural Science Foundation of China (31371460)

- Shunji Jia

Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China (2012CB945100)

- Shunji Jia

Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China (2011CB943800)

- Anming Meng

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jiawei Wu and Jue Wang for help with MESG-based single-turnover assay, Wei Wu for providing hFz5-Myc, Bailong Xiao for STIM1-mCherry, Douglas Kim for pGP-CMV-GCaMP6 (Addgene plasmid #40753) and Randall Moon for XE128 Rfz2 TG2myc CS2+ (Addgene plasmid #16796). We are grateful to the members of the Meng Laboratory and Drs. Qiang Wang and Wei Wu for helpful discussion and technical assistance. This work was financially supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (#31522035 and #31371460), Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China (#2012CB945100, #2011CB943800).

Ethics

Animal experimentation: Fishes were handled according to the institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) protocols (AP#13-MAM1), which were approved and permitted by the Tsinghua University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Version history

- Received: February 27, 2017

- Accepted: April 30, 2017

- Accepted Manuscript published: May 2, 2017 (version 1)

- Version of Record published: May 9, 2017 (version 2)

Copyright

© 2017, Gong et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,896

- views

-

- 400

- downloads

-

- 23

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Biochemistry and Chemical Biology

- Cell Biology

Mediator of ERBB2-driven Cell Motility 1 (MEMO1) is an evolutionary conserved protein implicated in many biological processes; however, its primary molecular function remains unknown. Importantly, MEMO1 is overexpressed in many types of cancer and was shown to modulate breast cancer metastasis through altered cell motility. To better understand the function of MEMO1 in cancer cells, we analyzed genetic interactions of MEMO1 using gene essentiality data from 1028 cancer cell lines and found multiple iron-related genes exhibiting genetic relationships with MEMO1. We experimentally confirmed several interactions between MEMO1 and iron-related proteins in living cells, most notably, transferrin receptor 2 (TFR2), mitoferrin-2 (SLC25A28), and the global iron response regulator IRP1 (ACO1). These interactions indicate that cells with high MEMO1 expression levels are hypersensitive to the disruptions in iron distribution. Our data also indicate that MEMO1 is involved in ferroptosis and is linked to iron supply to mitochondria. We have found that purified MEMO1 binds iron with high affinity under redox conditions mimicking intracellular environment and solved MEMO1 structures in complex with iron and copper. Our work reveals that the iron coordination mode in MEMO1 is very similar to that of iron-containing extradiol dioxygenases, which also display a similar structural fold. We conclude that MEMO1 is an iron-binding protein that modulates iron homeostasis in cancer cells.

-

- Cell Biology

- Chromosomes and Gene Expression

Heat stress is a major threat to global crop production, and understanding its impact on plant fertility is crucial for developing climate-resilient crops. Despite the known negative effects of heat stress on plant reproduction, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain poorly understood. Here, we investigated the impact of elevated temperature on centromere structure and chromosome segregation during meiosis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Consistent with previous studies, heat stress leads to a decline in fertility and micronuclei formation in pollen mother cells. Our results reveal that elevated temperature causes a decrease in the amount of centromeric histone and the kinetochore protein BMF1 at meiotic centromeres with increasing temperature. Furthermore, we show that heat stress increases the duration of meiotic divisions and prolongs the activity of the spindle assembly checkpoint during meiosis I, indicating an impaired efficiency of the kinetochore attachments to spindle microtubules. Our analysis of mutants with reduced levels of centromeric histone suggests that weakened centromeres sensitize plants to elevated temperature, resulting in meiotic defects and reduced fertility even at moderate temperatures. These results indicate that the structure and functionality of meiotic centromeres in Arabidopsis are highly sensitive to heat stress, and suggest that centromeres and kinetochores may represent a critical bottleneck in plant adaptation to increasing temperatures.