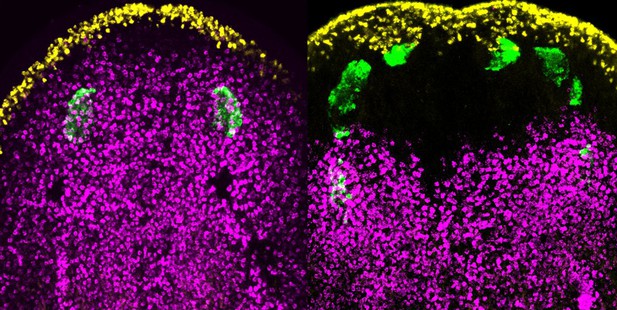

Left: A normal planarian, with eyes shown in green. Right: The eyes of a genetically modified planarian form repeatedly. Image credit: Li et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Many animals are able to regenerate tissue that has been lost through illness or injury. Flatworms called planarians have long been used to study tissue regeneration because of their remarkable ability to completely regenerate their whole body from small pieces of tissue. Furthermore, the stem cells of adult planarians continually produce new cells to replace dying cells in a process called tissue turnover.

For regeneration and tissue turnover to be successful, it is important for the new cells to form in the right location in the body; for example, new eye cells need to form in the head. Genes known as position control genes are active in muscle at specific locations along the body of a flatworm to regulate both regeneration and tissue turnover. However, it was not clear how these genes coordinate with stem cells to produce new cells in the correct positions in the body.

Li et al. examined the effects of a gene known as nr4A that is particularly active in muscle at the head and tail ends of planarians. Using a technique called RNA interference to decrease the activity of nr4A in planarians disrupted the patterns of tissues at each end of the flatworms. Over time, the activity of the position control genes also became restricted to locations progressively farther away from the head and tail. As a result, cells that were intended to replace tissues in the head or tail were deposited increasingly far away from these locations. For example, new eyes formed repeatedly in the planarians, with each set farther away from the head tip than the last. Li et al. propose that these disruptions of normal tissue patterning ensue because the cells that organize such patterns at the ends of the planarian (the poles) are themselves misplaced within the existing body pattern.

The nr4A gene can be found in a wide range of animal species. Understanding how this gene affects tissue patterns in planarians could therefore also help researchers to discover how adult tissue patterns form and are maintained in animals more generally.