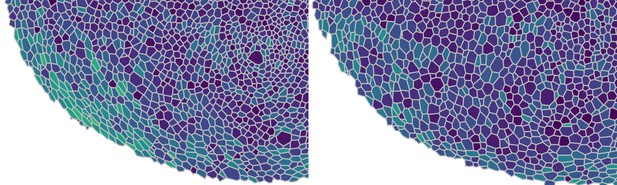

In the developing wing of a fruit fly larva, deactivating a protein that can sense physical forces leads to issues in the way cells acquire their characteristically elongated shape (normal wing is on the left; altered wing on the right). Image credit: Natalie Dye (CC BY 4.0)

During development, carefully choreographed cell movements ensure the creation of a healthy organism. To determine their identity and place across a tissue, cells can read gradients of far-reaching signaling molecules called morphogens; in addition, physical forces can play a part in helping cells acquire the right size and shape. Indeed, cells are tightly attached to their neighbors through connections linked to internal components. Structures or proteins inside the cells can pull on these junctions to generate forces that change the physical features of a cell. However, it is poorly understood how these forces create patterns of cell size and shape across a tissue.

Here, Dye, Popovic et al. combined experiments with physical models to examine how cells acquire these physical characteristics across the developing wing of fruit fly larvae. This revealed that cells pushing and pulling on one another create forces that trigger internal biochemical reorganization – for instance, force-generating structures become asymmetrical. In turn, the cells exert additional forces on their neighbors, setting up a positive feedback loop which results in cells adopting the right size and shape across the organ. As such, cells in the fly wing can spontaneously self-organize through the interplay of mechanical and biochemical signals, without the need for pre-existing morphogen gradients.

A refined understanding of how physical forces shape cells and organs would help to grasp how defects can emerge during development. This knowledge would also allow scientists to better grow tissues and organs in the laboratory, both for theoretical research and regenerative medicine.