Proteostress: Mechanosensory neurons under pressure

Being a neuron is stressful. Neurons tend not to be replaced in the body, so they need to remain healthy and able to adjust to changes in their environment and withstand a variety of chemical, electrical and mechanical challenges.

Keeping neurons healthy involves removing damaged proteins and replacing them with functional copies, and cells rely on a wide range of mechanisms to ensure that this happens (Redmann et al., 2016). However, damaged proteins can accumulate over time, and the build-up of such proteins, called proteostress, has been linked to Alzheimer’s disease and a number of other neurodegenerative diseases.

In the small nematode worm C. elegans, stressed neurons have been found to release large extracellular vesicles, known as exophers, which contain damaged organelles, large protein complexes and other protein aggregates (Melentijevic et al., 2017; Cocucci and Meldolesi, 2015, Cooper et al., 2021). However, the mechanism behind the extrusion of these exophers – which can measure up to 10 micrometers in diameter – remains unclear.

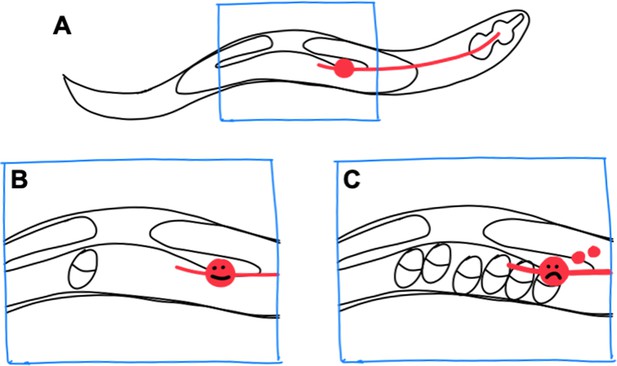

Now, in eLife, Monica Driscoll and colleagues – including Guoqiang Wang, Ryan Guasp and Sangeena Salam as joint first authors – report that C. elegans produces exophers in response to mechanical stress (Wang et al., 2024). The researchers – who are based at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine – studied neurons called lateral microtubule neurons, which are sensitive to touch and other mechanical forces. These neurons run along almost half of the length of the worm: the cell body is located near the uterus, and a long protrusion or neurite extends all the way to the head (Figure 1).

Exopher production by stressed neurons in C. elegans.

(A) In the C. elegans hermaphrodite worm, the reproductive system consists of two gonad arms, which contain the germline, and a common uterus (indicated by the blue box), where eggs accumulate before they are laid. The cell body of a lateral microtubule neuron (red circle) is in close proximity to the uterus, and the neurite of this neuron (red line) extends all the way to the head of the worm. (B) When only a small number of eggs are in the uterus, the neuron does not produce exophers. (C) However, when eggs accumulate in the uterus, the cell body becomes stressed and exophers (small red circles) are released.

Wang et al. analyzed the production of exophers in neurons expressing a fluorescent protein known as mCherry. High levels of expression of mCherry lead to proteostress in the neurons and also made it possible to trace the production and extrusion of exophers.

The experiments revealed that the release of the exophers varied with time, reaching a peak when the number of eggs in the uterus was at its highest. Using a variety of different genetic manipulations, Wang et al. showed that blocking the production of eggs inhibited the production of exophers, while increasing the load of eggs in the uterus promoted exopher production.

Moreover, the researchers found that the position of the neurons relative to the eggs mattered, and that neurons with cell bodies in the ‘egg zone’ produced more exophers. Likewise, in mutant worms with an expanded egg zone, neurons in the general vicinity of the zone produced large numbers of exophers, whereas those outside the zone did not.

Eggs distort the uterus and press into the surrounding tissues, so it is possible that the production of exophers is triggered by the physical presence of the eggs, rather than by chemical signals released by them. Wang et al. showed that filling the uterus with anything – dead eggs, unfertilized oocytes, or a buffer solution – leads to the production of exophers, which suggests that this process is triggered by the physical presence of the eggs.

Many intriguing questions remain. For example, how do neurons sense the mechanical signal, and how exactly does mechanical stress lead to the production of exophers? Wang et al. suggest that exopher production could be mediated through mechanosensitive ion channels such as PEZO-1/Peizo (Delmas et al., 2022). This ion channel is expressed in many tissues in C. elegans, including the lateral microtubule neurons, and an influx of calcium ions through it could stimulate the release of exophers. Alternatively, mechanical information could be transmitted via the extracellular matrix to integrins or other receptor proteins on the surface of the neuron. Moreover, the nuclei of some neurons are able to sense pressure (Niethammer, 2021), and a role for the nuclei in sensing mechanical forces would be consistent with the fact that exopher production is influenced by the position of the cell body, rather than the position of the neurites.

It remains to be seen if exophers are merely responsible for waste disposal, or if they also transmit products and/or information between cells. For example, C. elegans embryos can stimulate muscle cells to release exophers that are full of yolk: these exophers are then taken up by oocytes, and the yolk is used as food by the developing embryos (Turek et al., 2021). Exophers released from neurons can be also taken up by other cells and may potentially convey information about the stressed state of the worm to these other cells (Melentijevic et al., 2017; Turek et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023).

Cell-maintenance systems, such as autophagy, are important for the survival of organisms, but the production of exophers may provide an important backup. For example, it was shown recently that exopher production can extend lifespan when autophagy is blocked in C. elegans neurons (Yang et al., 2024). A better understanding of the conserved mechanisms of exopher production and function may help reveal how neurons adapt and survive under stressful conditions, and further elucidate the full potential of exophers.

References

-

Ectosomes and exosomes: shedding the confusion between extracellular vesiclesTrends in Cell Biology 25:364–372.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2015.01.004

-

Components and mechanisms of nuclear mechanotransductionAnnual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 37:233–256.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-cellbio-120319-030049

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: March 13, 2024 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2024, Cram

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 488

- views

-

- 32

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Neuroscience

Primates can recognize objects despite 3D geometric variations such as in-depth rotations. The computational mechanisms that give rise to such invariances are yet to be fully understood. A curious case of partial invariance occurs in the macaque face-patch AL and in fully connected layers of deep convolutional networks in which neurons respond similarly to mirror-symmetric views (e.g. left and right profiles). Why does this tuning develop? Here, we propose a simple learning-driven explanation for mirror-symmetric viewpoint tuning. We show that mirror-symmetric viewpoint tuning for faces emerges in the fully connected layers of convolutional deep neural networks trained on object recognition tasks, even when the training dataset does not include faces. First, using 3D objects rendered from multiple views as test stimuli, we demonstrate that mirror-symmetric viewpoint tuning in convolutional neural network models is not unique to faces: it emerges for multiple object categories with bilateral symmetry. Second, we show why this invariance emerges in the models. Learning to discriminate among bilaterally symmetric object categories induces reflection-equivariant intermediate representations. AL-like mirror-symmetric tuning is achieved when such equivariant responses are spatially pooled by downstream units with sufficiently large receptive fields. These results explain how mirror-symmetric viewpoint tuning can emerge in neural networks, providing a theory of how they might emerge in the primate brain. Our theory predicts that mirror-symmetric viewpoint tuning can emerge as a consequence of exposure to bilaterally symmetric objects beyond the category of faces, and that it can generalize beyond previously experienced object categories.

-

- Neuroscience

The nucleus incertus (NI), a conserved hindbrain structure implicated in the stress response, arousal, and memory, is a major site for production of the neuropeptide relaxin-3. On the basis of goosecoid homeobox 2 (gsc2) expression, we identified a neuronal cluster that lies adjacent to relaxin 3a (rln3a) neurons in the zebrafish analogue of the NI. To delineate the characteristics of the gsc2 and rln3a NI neurons, we used CRISPR/Cas9 targeted integration to drive gene expression specifically in each neuronal group, and found that they differ in their efferent and afferent connectivity, spontaneous activity, and functional properties. gsc2 and rln3a NI neurons have widely divergent projection patterns and innervate distinct subregions of the midbrain interpeduncular nucleus (IPN). Whereas gsc2 neurons are activated more robustly by electric shock, rln3a neurons exhibit spontaneous fluctuations in calcium signaling and regulate locomotor activity. Our findings define heterogeneous neurons in the NI and provide new tools to probe its diverse functions.