How scent and nectar influence floral antagonists and mutualists

Figures

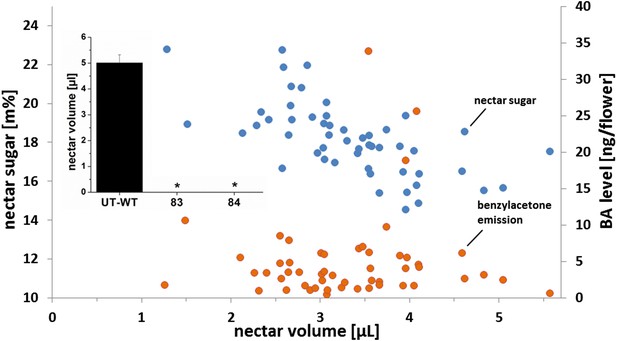

Characterization of 52 plants from different natural populations.

Mean standing nectar volume (n = 6 to 8 flowers/plant), nectar sugar concentration (n = 6 to 8 flowers/plant), and benzylacetone (BA) level (n = 1 flower/plant). Nectar volume and sugar concentration were measured from newly opened flowers at the end of the nectar production period (5–6 am). BA level was measured over the night (8 pm–6 am) and calculated from peak areas normalized using tetralin as an internal standard. Inset: mean (+SE) standing nectar volume in newly opened flowers at the end of the nectar production period (5–6 am) in three native phenotypes (Ut-WT, 83, and 84; n = 7–9) found within a separate sample of 424 native Nicotiana attenuata plants that were screened for the presence of nectar. Asterisks indicate significant differences, as informed by a nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test p < 0.05.

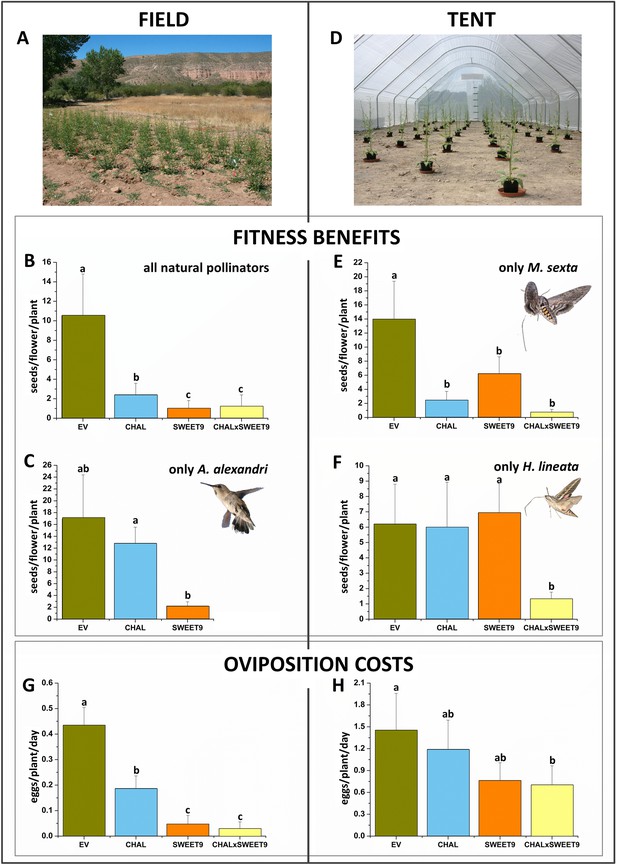

Benefits and cost of floral scent and nectar, as revealed from pollination and oviposition experiments in the field and tent.

Means +SEM of either seed production of antherectomized flowers or oviposition by Manduca sexta on transformed plants silenced in the production of floral scent (CHAL), floral nectar (SWEET9), or both (CHALxSWEET9) in comparison to empty vector control plants (EV). (A) Field plot in N. attenuata's native habitat at the Lytle ranch preserve in Santa Clara, Utah, USA. (B) Seeds sired from pollen transferred by the native community of floral visitors over the complete life span of a flower (3 days). (C) Exclusive pollination by Archilochus alexandri hummingbirds in the field during a 12 hr day. (D) Tent set-up used for single species pollinations in Isserstedt, Germany. Seeds sired from pollination of single M. sexta (E) or Hyles lineata (F) individuals during a 9-hr night. Eggs oviposited per transformed line (n = 10) on different days by the native community of M. sexta in the field (G) or by single individuals in the tent (H). Letters indicate significant differences inferred by a Friedman signed rank test p < 0.05.

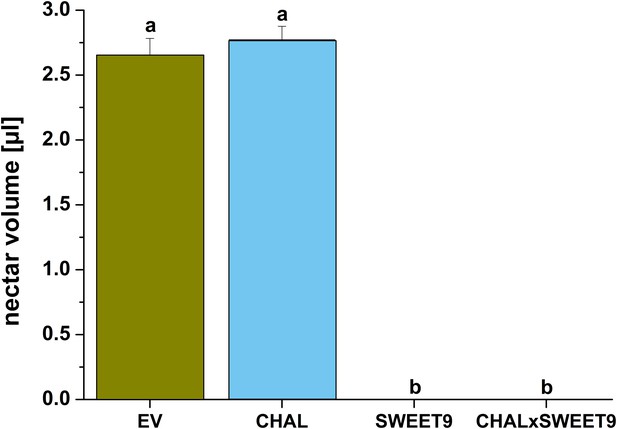

Nectar accumulation in flowers of transformed lines in the field.

Mean (+SE) standing nectar volume in newly opened flowers at the end of the nectar production period (5–6 am) in the field. Different letters indicate significant differences, as informed by a Friedman signed rank test p < 0.05.

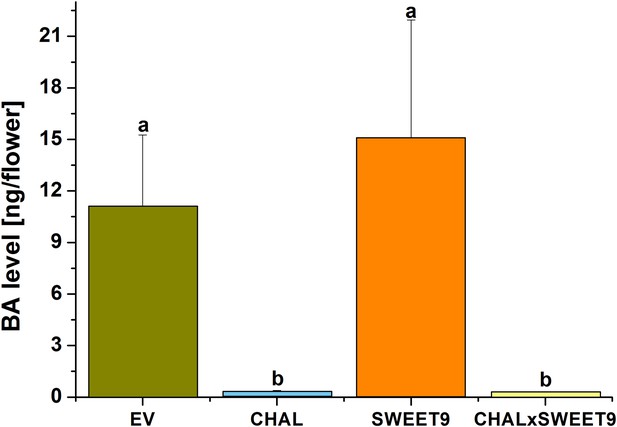

Analysis of flower volatiles.

Benzylacetone (BA) level from flowers in the field during the first night of opening (bars represent mean +SE amount of BA trapped per flower, n = 8). Different letters indicate significant differences, as informed by Friedman signed rank test p < 0.05.

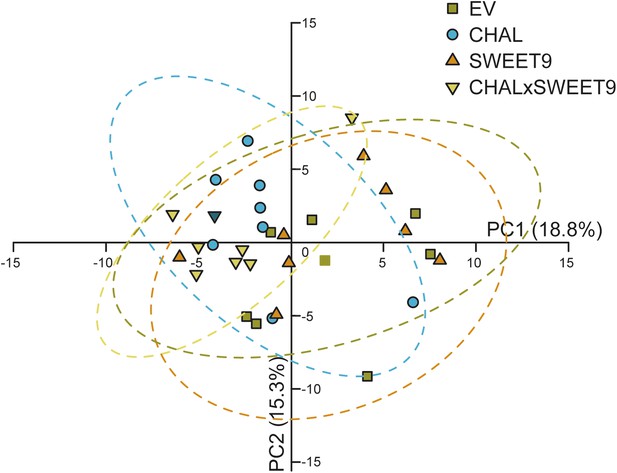

Principal components analysis (PCA) of leaf volatiles.

Leaf volatiles were collected overnight from un-attacked leaves from seven individual plants per genotype. 94 volatiles were detected and analyzed by PCA, and principal components (PCs) 1 and 2 of the transgenic lines were plotted against each other (dashed circles represent 95% confidence intervals).