Olfaction: Catching more flies with vinegar

A common expression would have us believe that ‘you can catch more flies with honey than with vinegar’. But this is not true in the case of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster (xkcd, 2007). Adult flies forage for microbes on overripe fruit, relying on their sense of smell to detect the acetic acid (the chemical that gives vinegar its pungent aroma) that accumulates as the fruit ferments. However, flies tend to ignore or even avoid both low levels of vinegar (which suggest that the fruit is not ripe enough) and high levels of vinegar (which suggest that the fruit might be rotten).

Now, in eLife, Jing Wang and co-workers at the University of California, San Diego—including Kang Ko as first author—elegantly reveal what happens in flies' brains that allows them to pursue a broader range of vinegar odor concentrations when hungry (Ko et al., 2015). Their data also show that starvation has a more nuanced influence on the early processing of olfactory information than was previously anticipated: hunger does more than just tune up the flies' sensitivity to food odors. Instead, it triggers specific responses (both excitatory and inhibitory) that encourage the flies to forage on sub-optimal food sources. In doing so, Ko et al. possibly provide additional evidence to support the notion that it is not wise to go grocery shopping on an empty stomach, lest hunger signals may impair your ability to discriminate good food from bad.

Ko et al.'s work is the culmination of a series of studies that have addressed how Drosophila process information about this important food odor. In fruit flies, much like in humans and other vertebrates, the olfactory neurons that detect specific volatile chemicals wire up to discrete clusters of synapses within the brain called glomeruli. Olfactory neurons that detect the same chemical all connect to the same glomerulus. Depending on the concentration, vinegar odor activates 6 to 8 of the 40 or so glomeruli in the fruit fly brain. However, a previous landmark study from the Wang group revealed that the activity of a single olfactory glomerulus, referred to as DM1, could explain most of a fly's attraction to vinegar (Semmelhack and Wang, 2009). Turning off the receptors that connect to DM1 caused the flies to ignore the odor of vinegar. On the other hand, restoring only the activity of DM1 neurons in otherwise ‘anosmic’ flies (that is, flies that have lost almost all sense of smell) was enough to make them attracted to vinegar again.

Higher concentrations of vinegar recruit just one extra glomerulus, called DM5, and the activity of DM5 on its own can explain why flies avoid vinegar if the odor is too strong (Semmelhack and Wang, 2009). Hence, the competitive interaction between DM1 and DM5 (which are activated at different vinegar odor concentrations) may ultimately determine whether the fly decides to approach a potential food source or to stay away.

Hunger has a profound impact on animal behavior, and hungry flies find a small drop of vinegar-laced food much more quickly than flies that have been fed (Root et al., 2011). The hormone insulin indirectly mediates this effect. Starvation causes insulin levels to plummet, triggering a chain of events that ultimately causes DM1 olfactory neurons to increase the expression of a specific receptor protein. This receptor detects a signaling molecule called ‘short neuropeptide F’. Upon binding to the receptor, this neuropeptide effectively amplifies, or turns up the ‘gain’ of, DM1 activity. Since DM1 neurons control a fruit fly's attraction to vinegar, this finding seemed to elegantly explain how insulin signaling can lead hungry flies to look more widely for food.

It now transpires that this is not the whole story. By extending the range of odor concentrations tested, Ko et al. now find that this mechanism only explains how hungry flies boost their attraction to low vinegar odor concentrations. At higher concentrations, starved flies still pursue vinegary food more robustly than fed controls, even when signaling mediated by short neuropeptide F is reduced (Ko et al., 2015). Could an additional neuropeptide account for this difference? To search for this missing hunger signal, Ko et al. surveyed other receptor proteins, looking for those that were increased in sensory neurons as a result of starvation. The Tachykinin receptor (called DTKR for short) emerged as a strong candidate, especially because it was known that it can tune down the responses of the fly's olfactory neurons (Ignell et al., 2009).

The rest of Ko et al.'s story beautifully follows a logical script: knocking down the levels of DTKR indeed reduced food-finding behavior in hungry flies exposed to high, but not low, vinegar odor concentrations. Similarly, DM5 (the glomerulus responsible for avoidance of high levels of vinegar) was less active in starved flies, but its activity could be brought back up to that of a fed fly when DTKR was knocked-down. Finally, Ko et al. identified insulin as the likely signal that acts upstream of DTKR in starving flies.

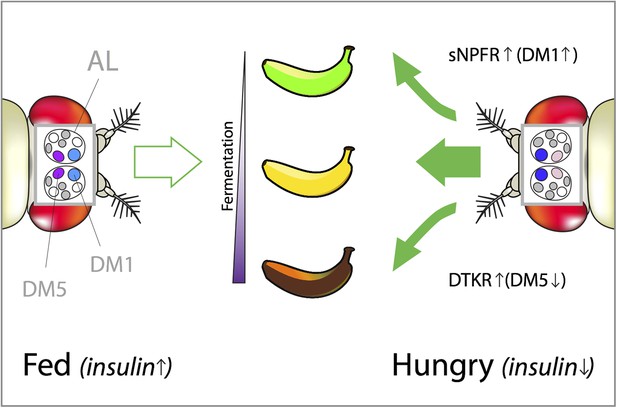

Taken together, the data suggest a model in which falling insulin levels in starving flies trigger two complementary neuropeptide signaling systems involving short neuropeptide F and Tachykinin. One helps the transmission of signals at the DM1 glomerulus, which makes the flies more sensitive to attractive food odors. In parallel, the other turns down transmission at DM5, which makes the flies less likely to avoid normally unpleasant or aversive smells. Together, these systems allow flies to pursue less-than-optimal food sources in times of shortage (Figure 1).

How hunger influences the attractiveness of food odors in Drosophila.

Vinegar (or acetic acid) is the ultimate product of the fermentation process in fruit, which is why fruit flies are attracted to vinegar odor. However, both low and high concentrations of vinegar odor leave flies indifferent (left). This is because low concentrations indicate that the fruit is just-ripe (green banana), whereas high concentrations mean that it is rotten (brown banana). Hungry flies behave differently because the low levels of insulin caused by starvation trigger two distinct neuropeptide signaling systems that reshape their olfactory responses (right). In hungry flies, the receptor for short neuropeptide F (called sNPFR) is upregulated in a subset of olfactory neurons. This helps the transmission of signals within the DM1 glomerulus, which increases the sensitivity to low concentrations of attractive food odors. In parallel, elevated Tachykinin signaling (through the DTKR receptor) inhibits the transmission of signals within the DM5 glomerulus. This decreases the avoidance of normally unpleasant smells (such as high concentrations of vinegar). Together these effects allow the pursuit of less-than-optimal food sources (depicted by the green arrows pointing toward the just-ripe and rotten bananas). DM1 and DM5 are specific glomeruli found in the antennal lobe (AL) of the fly brain and their color intensity represents the strength of their activation in fed vs hungry flies.

This study powerfully demonstrates the strengths of the fly model as a platform to study how the brain computes sensory stimuli. From clever behavioral assays, to sophisticated genetic manipulations and imaging of brain activity, the work describes how an important sensory cue is handled in different ways depending on the internal state of the animal (that is, hungry or not). Since what is true for the fly is often—at least in outline—true for man, the area of research is now ripe to contribute principles of sensory processing that may be applicable to many, if not all, animal species.

References

-

Presynaptic peptidergic modulation of olfactory receptor neurons in DrosophilaProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA 106:13070–13075.https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0813004106

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2015, Jouandet and Gallio

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 2,994

- views

-

- 194

- downloads

-

- 5

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Neuroscience

Perceptual systems heavily rely on prior knowledge and predictions to make sense of the environment. Predictions can originate from multiple sources of information, including contextual short-term priors, based on isolated temporal situations, and context-independent long-term priors, arising from extended exposure to statistical regularities. While the effects of short-term predictions on auditory perception have been well-documented, how long-term predictions shape early auditory processing is poorly understood. To address this, we recorded magnetoencephalography data from native speakers of two languages with different word orders (Spanish: functor-initial vs Basque: functor-final) listening to simple sequences of binary sounds alternating in duration with occasional omissions. We hypothesized that, together with contextual transition probabilities, the auditory system uses the characteristic prosodic cues (duration) associated with the native language’s word order as an internal model to generate long-term predictions about incoming non-linguistic sounds. Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that the amplitude of the mismatch negativity elicited by sound omissions varied orthogonally depending on the speaker’s linguistic background and was most pronounced in the left auditory cortex. Importantly, listening to binary sounds alternating in pitch instead of duration did not yield group differences, confirming that the above results were driven by the hypothesized long-term ‘duration’ prior. These findings show that experience with a given language can shape a fundamental aspect of human perception – the neural processing of rhythmic sounds – and provides direct evidence for a long-term predictive coding system in the auditory cortex that uses auditory schemes learned over a lifetime to process incoming sound sequences.

-

- Cell Biology

- Neuroscience

Reactive astrocytes play critical roles in the occurrence of various neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis. Activation of astrocytes is often accompanied by a glycolysis-dominant metabolic switch. However, the role and molecular mechanism of metabolic reprogramming in activation of astrocytes have not been clarified. Here, we found that PKM2, a rate-limiting enzyme of glycolysis, displayed nuclear translocation in astrocytes of EAE (experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis) mice, an animal model of multiple sclerosis. Prevention of PKM2 nuclear import by DASA-58 significantly reduced the activation of mice primary astrocytes, which was observed by decreased proliferation, glycolysis and secretion of inflammatory cytokines. Most importantly, we identified the ubiquitination-mediated regulation of PKM2 nuclear import by ubiquitin ligase TRIM21. TRIM21 interacted with PKM2, promoted its nuclear translocation and stimulated its nuclear activity to phosphorylate STAT3, NF-κB and interact with c-myc. Further single-cell RNA sequencing and immunofluorescence staining demonstrated that TRIM21 expression was upregulated in astrocytes of EAE. TRIM21 overexpressing in mice primary astrocytes enhanced PKM2-dependent glycolysis and proliferation, which could be reversed by DASA-58. Moreover, intracerebroventricular injection of a lentiviral vector to knockdown TRIM21 in astrocytes or intraperitoneal injection of TEPP-46, which inhibit the nuclear translocation of PKM2, effectively decreased disease severity, CNS inflammation and demyelination in EAE. Collectively, our study provides novel insights into the pathological function of nuclear glycolytic enzyme PKM2 and ubiquitination-mediated regulatory mechanism that are involved in astrocyte activation. Targeting this axis may be a potential therapeutic strategy for the treatment of astrocyte-involved neurological disease.