Learning: Hippocampal neurons wait their turn

Our days are full of mental countdowns: how long until the coffee is done brewing? Until the light turns green? Until this gel has finished running? Predicting the future state of the world from the present is critical for flexible behaviour, allowing us to move beyond reflexive reactions and instead towards charting a course that minimises punishment or improves our chances of reward. We routinely link cues (e.g., coffee starts to brew) and outcomes (coffee is ready) that are separated by seconds, minutes, or longer. At the cellular level, learning involves making changes to the strength of the connections between neurons, but these changes are only triggered when two neurons are active within about 100 milliseconds of each other (Levy and Steward, 1983; Feldman, 2012). Thus, there is an apparent mismatch between the timescales for behavioural learning and neural plasticity.

How, then, does the brain link together related events that are separated in time? One possibility is that it prolongs neuron firing in some way, maintaining the neural signal from the initial cue. Several regions of the brain, most notably the frontal cortex, show persistently elevated neural activity while animals hold information in their short-term memory (Funahashi, 2006). However, simply sustaining neural activity does not carry information about how much time has passed.

Recently, recordings from a region of the brain called the hippocampus in rats have revealed ‘time cells’ that fire in repetitive sequences during the interval between an initial cue and a delayed action (MacDonald et al., 2011). By providing time information, these cells complement the well-known role of hippocampal ‘place cells’ that fire when an animal is in a specific location. It has been proposed that these neural signals for place and time help to form episodic memories that link together a series of events occurring at different locations, supplying our remembered experience (Eichenbaum, 2013).

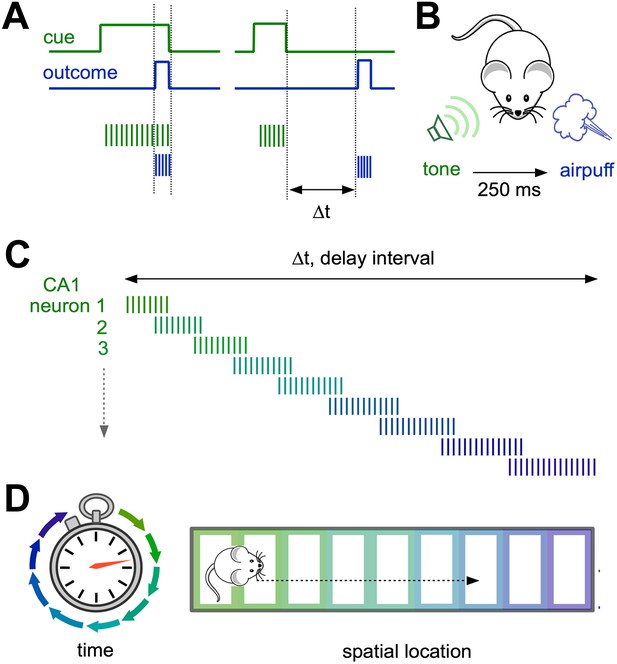

Now, in eLife, Mehrab Modi, Ashesh Dhawale and Upinder Bhalla of the National Centre for Biological Sciences in India show that sequences of neural activity in the hippocampus also contribute to another form of time-based learning. Using a classic eyeblink experiment, they trained animals to blink at a certain length of time after they heard a specific tone in order to avoid a puff of air directed at their eyes (Figure 1B). Two-photon Ca2+ imaging during the training period revealed how neurons in the hippocampus responded as mice learnt to blink at the right time.

Neural representations of elapsed time in the hippocampus.

(A and B) When a cue (such as a specific sound; green) and an outcome (such as a puff of air directed at the eyes; blue) overlap in time (left) and drive overlapping neural activity in different groups of neurons (vertical green and blue lines), standard plasticity processes can account for learning. However, when the cue and the outcome are separated by more than ∼100 milliseconds (right), the mechanisms for linking these events in the brain are less well understood. (C) Modi et al. show that the time interval between the initial cue and the predicted arrival of the puff of air is bridged by temporally ordered sequences of activated neurons in hippocampal area CA1. (D) Ordered sequences are a common feature of activity in CA1, and can represent the animal’s trajectory in both time (left) and space (right).

Distinct groups of cells in an area of the hippocampus known as CA1 were selectively active at each successive time point after the tone, so that their firing collectively bridged the entire delay period. CA1 therefore explicitly encodes elapsed time, with each ‘tick’ of the hippocampal clock represented by a specific set of activated neurons (Figure 1C). Importantly, reliable neural sequences emerged as the animals mastered the timing of the blink response.

While neural sequences provide an appealing explanation behind the mental stopwatch, it is unclear how they are generated in the brain. Computational work suggests that training can produce ordered sequences in appropriately connected neural networks (Goldman, 2009). The area of the hippocampus known as CA3, which provides much of the input into CA1, constitutes such a circuit. Furthermore, time cell firing in CA1 resembles the output of this model (MacDonald et al., 2011).

By looking at the activity of large numbers of neurons, Modi and colleagues provide experimental evidence that CA1 sequences are likely to result from changes in the input received from CA3. This involved assessing the noise correlations—the similarities in the random fluctuations in neural activity at rest—which arise when two neurons are either directly connected, or are both driven by the same source. Noise correlations between CA1 cells increased early in training, suggesting that their inputs from CA3 were the site of the neural changes driven by learning (Modi et al., 2014). While correlations mostly decreased again later in training, they remained high among the CA1 cells responding at the same time point, further suggesting that their final time-selectivity depends on a common source in CA3.

Similar correlation effects have been described in pairs of CA1 place cells in rats exploring a novel spatial environment (Cheng and Frank, 2008), suggesting that modifying the input from CA3 to CA1 may contribute to learning about both time and place. Interestingly, sequential activity also occurs as animals navigate through successive locations in space, driving firing in different place cells (Figure 1D).

Ordered sequences of firing are widespread in neural processing, appearing not only in other delay-based tasks (Funahashi, 2006) but also in spatial navigation (O’Keefe and Recce, 1993), complex motor actions (Hahnloser et al., 2002), and sensory perception (Shusterman et al., 2011). It will be important to understand whether these diverse contexts share common principles for generating sequences of neural firing. Since sequences are generated internally in the brain, independently of external input, identifying the region where they arise is a major goal. The findings of Modi, Dhawale and Bhalla further this effort by implicating area CA3 as this source in a task that depends solely on time.

In the future, direct measurements from CA3 itself should help to clarify its role in generating new neuron firing sequences. In spatial learning tasks, suppressing the CA3 output demonstrates that it contributes to the initial formation of new place fields, and so determines the location where CA1 place cells fire (Nakashiba et al., 2008). Similar approaches could help further define CA3’s role in learning about time intervals as well. Finally, while the delay period used here was less than a second, we often face time contingencies spanning much more extended intervals. A major remaining challenge will also be to understand how the brain tracks delays on very long timescales—such as those needed for publishing scientific papers.

References

-

Prefrontal cortex and working memory processesNeuroscience 139:251–261.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.003

-

Precise olfactory responses tile the sniff cycleNature Neuroscience 14:1039–1044.https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2877

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: March 25, 2014 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2014, Gao and Davison

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 860

- views

-

- 55

- downloads

-

- 0

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Neuroscience

Nociceptive sensory neurons convey pain-related signals to the CNS using action potentials. Loss-of-function mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.7 cause insensitivity to pain (presumably by reducing nociceptor excitability) but clinical trials seeking to treat pain by inhibiting NaV1.7 pharmacologically have struggled. This may reflect the variable contribution of NaV1.7 to nociceptor excitability. Contrary to claims that NaV1.7 is necessary for nociceptors to initiate action potentials, we show that nociceptors can achieve similar excitability using different combinations of NaV1.3, NaV1.7, and NaV1.8. Selectively blocking one of those NaV subtypes reduces nociceptor excitability only if the other subtypes are weakly expressed. For example, excitability relies on NaV1.8 in acutely dissociated nociceptors but responsibility shifts to NaV1.7 and NaV1.3 by the fourth day in culture. A similar shift in NaV dependence occurs in vivo after inflammation, impacting ability of the NaV1.7-selective inhibitor PF-05089771 to reduce pain in behavioral tests. Flexible use of different NaV subtypes exemplifies degeneracy – achieving similar function using different components – and compromises reliable modulation of nociceptor excitability by subtype-selective inhibitors. Identifying the dominant NaV subtype to predict drug efficacy is not trivial. Degeneracy at the cellular level must be considered when choosing drug targets at the molecular level.

-

- Neuroscience

Despite substantial progress in mapping the trajectory of network plasticity resulting from focal ischemic stroke, the extent and nature of changes in neuronal excitability and activity within the peri-infarct cortex of mice remains poorly defined. Most of the available data have been acquired from anesthetized animals, acute tissue slices, or infer changes in excitability from immunoassays on extracted tissue, and thus may not reflect cortical activity dynamics in the intact cortex of an awake animal. Here, in vivo two-photon calcium imaging in awake, behaving mice was used to longitudinally track cortical activity, network functional connectivity, and neural assembly architecture for 2 months following photothrombotic stroke targeting the forelimb somatosensory cortex. Sensorimotor recovery was tracked over the weeks following stroke, allowing us to relate network changes to behavior. Our data revealed spatially restricted but long-lasting alterations in somatosensory neural network function and connectivity. Specifically, we demonstrate significant and long-lasting disruptions in neural assembly architecture concurrent with a deficit in functional connectivity between individual neurons. Reductions in neuronal spiking in peri-infarct cortex were transient but predictive of impairment in skilled locomotion measured in the tapered beam task. Notably, altered neural networks were highly localized, with assembly architecture and neural connectivity relatively unaltered a short distance from the peri-infarct cortex, even in regions within ‘remapped’ forelimb functional representations identified using mesoscale imaging with anaesthetized preparations 8 weeks after stroke. Thus, using longitudinal two-photon microscopy in awake animals, these data show a complex spatiotemporal relationship between peri-infarct neuronal network function and behavioral recovery. Moreover, the data highlight an apparent disconnect between dramatic functional remapping identified using strong sensory stimulation in anaesthetized mice compared to more subtle and spatially restricted changes in individual neuron and local network function in awake mice during stroke recovery.