Philosophy of Biology: Immunology and individuality

Abstract

Immunology and philosophy have a rich history of dialogue. Immunologists have long been influenced by ideas from philosophy, notably the concept of 'self', and many philosophers have explored the conceptual, theoretical and methodological foundations of immunology. Here, I discuss two aspects of this dialogue: biological individuality and immunogenicity.

Main text

What do philosophers say about immunology, and to what extent can this be useful to immunologists? One remarkable feature of modern immunology is that it uses a vocabulary that has been strongly influenced by philosophy. The philosophical concepts of 'self' and 'nonself', in particular, have played a central role in immunology since the 1940s. Reflecting on this vocabulary enables us to better understand why it was adopted, what its underlying assumptions are, and whether it should be maintained or revised in light of what we know about immunology today.

In this article I show how a philosophical approach can shed light on two key aspects of current immunology. The first is biological individuality: what defines the unity, boundaries, uniqueness and persistence of a living thing according to immunology, especially in the context of what we are learning about the interactions between microbiota and the immune system? The second aspect is immunogenicity: that is, the ability of certain entities to trigger an effector immune response that destroys a target.

Immunological individuality

Our fascination with biological individuality dates back to Aristotle, possibly earlier, and has been a central issue in immunology from the end of the 19th century (Medawar, 1957; Richet, 1894). The fundamental question raised by reflections on biological individuality is what makes a living being a cohesive, relatively well-delineated and often unique entity that remains the 'same' through time despite undergoing constant change (Santelices, 1999; West et al., 2015). Biological individuality is relative in that it depends on the question being asked. Moreover, it comes in degrees, in so far that the four main elements of biological individuality – cohesion, delineation, uniqueness and persistence – can be expressed to different levels in a living being (Pradeu, 2016; Santelices, 1999).

Though immunology is not the only scientific field addressing the issue of biological individuality, it does make a major contribution to this question. The immune system plays a key role in monitoring every part of the organism and maintaining the cohesion between the components of that organism, making each individual unique and constantly re-establishing the boundaries between the organism and its environment (Pradeu, 2012).

The question of the self-nonself is particularly relevant in defining biological individuality and has been strongly shaped by the Australian virologist Macfarlane Burnet (Tauber, 1994). His conceptual and theoretical reflections on the self and not-self (inspired by philosophy) were later adopted by a vast majority of immunologists. Burnet suggested that every entity that is foreign to the organism is rejected by the immune system, while every entity that originates from that organism does not trigger an immune response (Burnet, 1969). This framework made it possible to account for various immune responses, from pathogens to grafts.

Burnet considered immunology to be more a philosophical problem, rather than a scientific one, and was strongly influenced by the mathematician and philosopher Alfred North Whitehead, who had given the notion of the self a central role in his philosophy (Anderson and Mackay, 2014). The dialogue between immunologists and philosophers has continued ever since: immunologists borrow concepts from philosophy, especially when they reflect on the issue of individuality, and reciprocally, many philosophers use immunology as a major source of inspiration (Cohen, 2009).

Philosophers have improved our understanding of how the conceptual framework of the self-nonself was built, and helped put into question its theoretical and empirical foundations (Pradeu, 2012; Swiatczak and Rescigno, 2012; Tauber, 1994). Scientific data collected since the 1990 s have revealed that the immune system also responds to endogenous components, that is, to the self. In fact, a significant degree of autoreactivity and autoimmunity is indispensable for a healthy immune system. Immune responses such as the phagocytosis of dead cells, tissue repair and regulatory responses are in most cases responses to the self (Rankin and Artis, 2018). Moreover, it is now clear that many foreign entities, such as microbial communities (known as microbiota), are actively tolerated by the immune system rather than eliminated (Chu and Mazmanian, 2013).

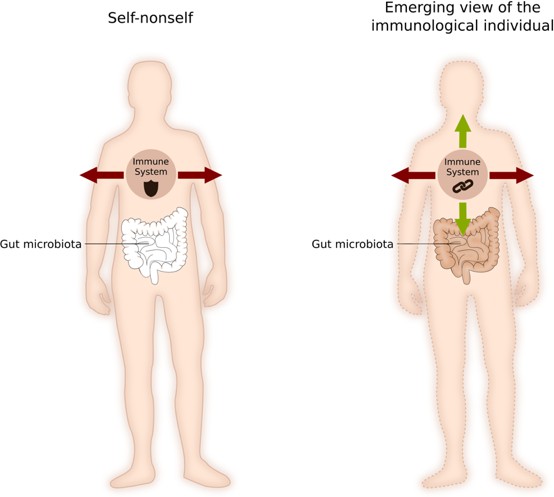

These developments have led many to conclude that the self-nonself framework should be revisited, and that we should switch from an internalist view (which sees the individual as insular, autonomous and endogenously built) to a more interactionist view (which sees an organism as an ecosystem that is constantly interacting with its environment; McFall-Ngai et al., 2013). Although biological individuality remains a key question in immunology, the way that scientists see it has changed: the notion of self-nonself has evolved to the idea of an individual made of heterogeneous elements with constantly redefined boundaries, in which the immune system can not only eliminate, but also actively tolerate the elements with which it interacts (Figure 1; Pradeu, 2012).

How immunology defines a biological individual.

According to the 'self-nonself' framework (left), the immune system is mainly a system for targeting and killing foreign bodies. Interfaces, such as the gut lumen, belong to the ‘outside’ of the organism, and boundaries are strict and fixed. According to the newly emerging 'immunological individual' framework (right), the immune system can eliminate self and nonself elements, it can tolerate self and nonself elements, but it also reinforces the cohesion between bodily constituents. In this framework, boundaries are constantly being redefined by the action of the immune system. Image credit: Wiebke Bretting (CC BY 4.0).

Immunogenicity

The self-nonself framework also offers an explanation of immunogenicity: that is, how an effector immune response (a response leading to the elimination or the neutralization of a target) is activated. Some hypotheses, such as the 'danger theory', suggest that the immune system does not distinguish between self and nonself: rather, it differentiates between things that cause damage and those that do not (Matzinger, 1994). However, together with fellow immunologists, I suggest another alternative: the discontinuity theory of immunity (Pradeu et al., 2013; Pradeu and Carosella, 2006).

The discontinuity theory proposes that effector immune responses are triggered by sudden changes in the molecular motifs that interact with the receptors of the immune system (e.g., pattern-recognition receptors, NK cell receptors, B cell receptors, T cell receptors and cytokine receptors). In contrast, a persistent motif, or a slowly appearing one, do not trigger an effector response, rather, it leads to a tolerogenic immune response (where a target will be accepted rather than eliminated). Space and time are important in the discontinuity theory: the vast majority of immune responses occur in tissues rather than in the blood, and different tissues have different baseline levels of immune activation, so any theory of the immune response must account for the tissue-specific nature of the response.

An immune response may be due to all sorts of sudden changes, and could be related to motifs being recognized and/or changes to the immune system (such as the migration of motifs or immune cells from one tissue to another, or the rapid appearance of a pathogen or a tumour). What clearly distinguishes the discontinuity theory from the self-nonself theory is that the criterion of immunogenicity is not the origin of the antigen (as it is in the self-nonself framework): rather, it is the speed of change in the relevant tissue (Table 1). Therefore, persistent or slowly appearing 'nonself motifs' are tolerated by the immune system, while fast-appearing 'self motifs' cause an effector response.

Different theories of immunogenicity.

The self-nonself theory and the discontinuity theory of immunity predict the same outcomes for persistent or slowly changing endogenous (self) elements, and also for suddenly appearing and/or rapidly changing exogenous (nonself) elements. The theories make different predictions for rapidly changing endogenous elements, and for persistent or slowly changing exogenous elements.

| Motifs | Examples | Self-nonself theory | Discontinuity theory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapidly changing endogenous elements | - Some significant bodily transformations, when uncontrolled (e.g., puberty, metamorphosis, pregnancy) | tolerogenic response | effector response |

| Persistent or slowly changing endogenous elements | - Usual functioning of the body | tolerogenic response | tolerogenic response |

| Persistent or slowly changing exogenous elements | - Many components of the microbiota acquired early during ontogeny - Chronic viruses | effector response | tolerogenic response |

| Suddenly appearing and/or rapidly changing exogenous elements | - Microorganisms that invade the organism suddenly - Most grafts | effector response | effector response |

This could be relevant for the field of onco-immunology (Ribas and Wolchok, 2018; Pauken and Wherry, 2015). For example, the discontinuity theory predicts that a slowly growing tumour triggers a tolerogenic immune response, whereas a tumour that is growing rapidly (or a tumour in a microenvironment that is changing rapidly) triggers an effector response. The discontinuity theory has also been used to shed light on a range of different topics, including the effects of chemotherapeutic agents on immunomodulation in cancer (Hodge et al., 2013), the constant 'education' of natural killer cells to ensure tolerance of bodily constituents (Boudreau and Hsu, 2018), repeated vaccinations in immunocompromised individuals (Rinaldi et al., 2014), and mathematical models of immune activation (Sontag, 2017). Depending on future experimental results, this theory will be enriched, revised or, perhaps, abandoned.

Conclusion

Immunology is one of the most theoretical and most philosophical fields within the life sciences, and the ongoing dialogues between immunologists and philosophers are likely to continue. The list of questions worth discussing include the following: i) How can we combine the various types and levels of explanation in immunology (from molecules to system) into an integrative framework? ii) Which principles should one use to offer satisfactory and fruitful classifications of immune components (Mantovani, 2016)? iii) How can immunology be enriched by contributions from other areas of biology and beyond (including physics and computer science?) iv) Can one define immunity and immunology? It is now clear that the immune system does many things besides defending against pathogens: for example, it is involved in development and tissue repair. As the field of immunology has become broader (to the extent that it overlaps with many areas of physiology), its boundaries have become blurred (Rankin and Artis, 2018; Truchetet and Pradeu, 2018). For these challenges and many others, a close alliance between philosophers, biologists and physicians seems full of promise.

Note

This Feature Article is part of the Philosophy of Biology collection.

References

-

Fashioning the immunological self: the biological individuality of F. Macfarlane BurnetJournal of the History of Biology 47:147–175.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10739-013-9352-1

-

Innate immune recognition of the microbiota promotes host-microbial symbiosisNature Immunology 14:668–675.https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.2635

-

Reflections on immunological nomenclature: in praise of imperfectionNature Immunology 17:215–216.https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.3354

-

Tolerance, danger, and the extended familyAnnual Review of Immunology 12:991–1045.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.005015

-

Overcoming T cell exhaustion in infection and cancerTrends in Immunology 36:265–276.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2015.02.008

-

BookThe Limits of the Self: Immunology and Biological IdentityOxford University Press.

-

The speed of change: towards a discontinuity theory of immunity?Nature Reviews Immunology 13:764–769.https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3521

-

The many faces of biological individualityBiology & Philosophy 31:761–773.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10539-016-9553-z

-

BookLa D Fense De l'Organisme: Cours De Physiologie De La Facult De M Decine (1893-1894)Paris: Typographie Chamerot et Renouard.

-

How many kinds of individual are there?Trends in Ecology & Evolution 14:152–155.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01519-5

Article and author information

Author details

Funding

H2020 European Research Council (637647 – IDEM)

- Thomas Pradeu

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Publication history

- Received: April 3, 2019

- Accepted: April 3, 2019

- Version of Record published: April 5, 2019 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2019, Pradeu

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 6,023

- views

-

- 722

- downloads

-

- 24

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Immunology and Inflammation

Environmental air irritants including nanosized carbon black (nCB) can drive systemic inflammation, promoting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and emphysema development. The let-7 microRNA (Mirlet7 miRNA) family is associated with IL-17-driven T cell inflammation, a canonical signature of lung inflammation. Recent evidence suggests the Mirlet7 family is downregulated in patients with COPD, however, whether this repression conveys a functional consequence on emphysema pathology has not been elucidated. Here, we show that overall expression of the Mirlet7 clusters, Mirlet7b/Mirlet7c2 and Mirlet7a1/Mirlet7f1/Mirlet7d, are reduced in the lungs and T cells of smokers with emphysema as well as in mice with cigarette smoke (CS)- or nCB-elicited emphysema. We demonstrate that loss of the Mirlet7b/Mirlet7c2 cluster in T cells predisposed mice to exaggerated CS- or nCB-elicited emphysema. Furthermore, ablation of the Mirlet7b/Mirlet7c2 cluster enhanced CD8+IL17a+ T cells (Tc17) formation in emphysema development in mice. Additionally, transgenic mice overexpressing Mirlet7g in T cells are resistant to Tc17 and CD4+IL17a+ T cells (Th17) development when exposed to nCB. Mechanistically, our findings reveal the master regulator of Tc17/Th17 differentiation, RAR-related orphan receptor gamma t (RORγt), as a direct target of Mirlet7 in T cells. Overall, our findings shed light on the Mirlet7/RORγt axis with Mirlet7 acting as a molecular brake in the generation of Tc17 cells and suggest a novel therapeutic approach for tempering the augmented IL-17-mediated response in emphysema.

-

- Immunology and Inflammation

SARS-CoV-2 vaccines have been used worldwide to combat COVID-19 pandemic. To elucidate the factors that determine the longevity of spike (S)-specific antibodies, we traced the characteristics of S-specific T cell clonotypes together with their epitopes and anti-S antibody titers before and after BNT162b2 vaccination over time. T cell receptor (TCR) αβ sequences and mRNA expression of the S-responded T cells were investigated using single-cell TCR- and RNA-sequencing. Highly expanded 199 TCR clonotypes upon stimulation with S peptide pools were reconstituted into a reporter T cell line for the determination of epitopes and restricting HLAs. Among them, we could determine 78 S epitopes, most of which were conserved in variants of concern (VOCs). After the 2nd vaccination, T cell clonotypes highly responsive to recall S stimulation were polarized to follicular helper T (Tfh)-like cells in donors exhibiting sustained anti-S antibody titers (designated as ‘sustainers’), but not in ‘decliners’. Even before vaccination, S-reactive CD4+ T cell clonotypes did exist, most of which cross-reacted with environmental or symbiotic microbes. However, these clonotypes contracted after vaccination. Conversely, S-reactive clonotypes dominated after vaccination were undetectable in pre-vaccinated T cell pool, suggesting that highly responding S-reactive T cells were established by vaccination from rare clonotypes. These results suggest that de novo acquisition of memory Tfh-like cells upon vaccination may contribute to the longevity of anti-S antibody titers.