TOR Signaling: A central role for a region in the middle

Cellular growth is a tightly regulated process that depends on the availability of energy and nutrients. Moreover, in multicellular species, the proliferation of cells must be coordinated across tissues and organs. Protein kinases called target of rapamycin (TOR) proteins and their mammalian ortholog mTOR have a central role in growth regulation. These proteins exert their function in two complexes called TORC1 and TORC2 (or mTORC1 and mTORC2 in mammals). These complexes act as regulatory hubs that integrate input signals concerning the availability of energy and nutrients or the presence of growth factors. With their outputs, the mTOR complexes control metabolism and protein biosynthesis, and influence cell cycle progression, autophagy and cytoskeletal organization (Laplante and Sabatini, 2012; Shimobayashi and Hall, 2014).

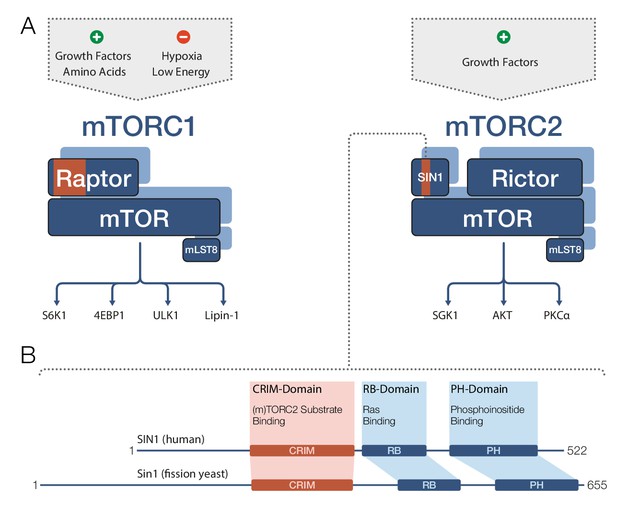

TOR and mTOR are very large proteins (containing approximately 2300–2600 amino acids) and are members of the PIKK family of regulatory kinases. Both mTOR complexes comprise mTOR and a protein called mLST8 (Figure 1A). mTORC1 also contains a protein called Raptor, whereas mTORC2 further includes the proteins Rictor and SIN1. In both complexes, the partner proteins of mTOR determine the target specificity of the mTOR kinase (Cameron et al., 2011; Nojima et al., 2003). mTORC1 phosphorylates a diverse set of targets involved in protein biosynthesis, metabolism and transcriptional regulation, while mTORC2’s most prominent targets are regulatory kinases of the AGC family.

Target recognition in mTOR complexes.

(A) The protein complexes mTORC1 and mTORC2 regulate cellular processes and growth via phosphorylation of substrate proteins mediated by the mTOR kinase domain. mTORC1 signaling (left) is stimulated by growth factors and amino acids, and is inhibited by low cellular energy levels and hypoxia (a shortage of oxygen). Conserved protein regions involved in target recognition in mTORC1 are located in the Raptor subunit (highlighted in orange). mTORC2 signaling (right) is activated by growth factors and the substrate binding domain identified by Tatebe et al. – the 'Conserved region in the middle' (CRIM) domain – is located in the SIN1 subunit (orange). Prominent downstream targets for each complex are indicated, including mTORC2 targets from the AGC kinase family: SGK1, AKT and PKCα. (B) The human SIN1 protein (top) and its fission yeast ortholog Sin1 (bottom) share similar domain organizations. The CRIM domain is involved in target recognition in both mTORC2 and TORC2. The variable N-terminal domain (which is to the left of the CRIM domain) has been implicated in SIN1/Sin1’s association with other constituents of mTORC2/TORC2. mLST8: mammalian lethal with SEC13 protein 8; PH: pleckstrin-homology; PIKK: phosphoinositide-3-kinase-related kinase; Raptor: regulatory-associated protein of mTOR; RB: (Raf-like) RAS-binding; Rictor: rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR; Sin1/SIN1: stress-activated map kinase-interacting protein 1.

In mTORC1, the Raptor N-terminal conserved (RNC) domain is known to be involved in the binding of linear recognition motifs in target proteins (Dunlop et al., 2009). Recent cryo-electron microscopy studies have provided a first glimpse at its function in mTORC1 (Aylett et al., 2016). The RNC domain is well positioned in the vicinity of the kinase active site to both recognize target motifs (Beugnet et al., 2003) and to sterically prevent – in cooperation with parts of mTOR – bulky non-target proteins accessing the kinase.

However, less is known about target recognition in TORC2 and mTORC2. Now, in eLife, researchers at the Nara Institute of Science and Technology, Osaka University and the University of California, Davis -- including Hisashi Tatebe and Shinichi Murayama as joint first authors, and Tatebe and Kazuhiro Shiozaki as corresponding authors -- report the results of a series of studies on human SIN1 and its fission yeast ortholog Sin1, that shed light on the conserved role of these proteins in target binding (Tatebe et al., 2017).

SIN1 and its orthologs are known to contain four domains (Figure 1B): a variable N-terminal region (Frias et al., 2006); the ‘Conserved region in the middle’ (CRIM); an RB domain; and a PH domain. However, the role of these domains in mTORC2 target recognition remained unclear, and structural data were only available for the isolated PH domain (Pan and Matsuura, 2012). Now Tatebe et al. have clearly shown that the CRIM domain has a key role in target recognition. In particular, they demonstrated that in fission yeast, the CRIM domain in Sin1 is primarily responsible for binding targets from the AGC kinase family. In human cell lines, the CRIM domain in SIN1 is at least involved in recognition of related targets, implying an evolutionary conserved role for this domain.

Based on earlier studies (Liu et al., 2015), SIN1 may even directly interact with the mTOR kinase domain in mTORC2. Thus, SIN1 might also be positioned to restrict access of the substrate to the kinase, eventually in cooperation with Rictor, similar to Raptor in mTORC1. Tatebe et al. also highlighted the crucial role of spatial proximity in target recognition by demonstrating that fusion of only the TORC2 target-binding CRIM domain into TORC1 is sufficient to let TORC1 phosphorylate a TORC2 substrate.

Tatebe et al. also report an NMR structure for the CRIM domain in fission yeast that reveals a ubiquitin-like fold with a prominent acidic loop. Mutational analysis confirms that target binding depends on the integrity of the CRIM domain and strongly suggests that the acidic loop is involved in binding.

With the functional role and structure of the CRIM domain now firmly established, researchers can start to address the many remaining questions about TORC2 target recognition. The NMR structure of the CRIM domain provides an excellent platform for a detailed analysis of the recognition of specific motifs in target substrates by SIN1. However, studies of the overall integration of SIN1 into mTORC2 will be required to address the consequences of SIN1-target binding for subsequent phosphorylation. Finally, work on target recognition in mTOR complexes together with recent structural and functional studies on other PIKK family kinases (Sibanda et al., 2017) may reveal the presence (or absence) of common principles in target recognition across the entire PIKK family.

References

-

mTORC2 targets AGC kinases through Sin1-dependent recruitmentBiochemical Journal 439:287–297.https://doi.org/10.1042/BJ20110678

-

PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-Dependent activation of the mTORC2 kinase complexCancer Discovery 5:1194–1209.https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0460

-

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) partner, Raptor, binds the mTOR substrates p70 S6 kinase and 4E-BP1 through their TOR signaling (TOS) motifJournal of Biological Chemistry 278:15461–15464.https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.C200665200

-

Structures of the pleckstrin homology domain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Avo1 and its human orthologue Sin1, an essential subunit of TOR complex 2Acta Crystallographica Section F Structural Biology and Crystallization Communications 68:386–392.https://doi.org/10.1107/S1744309112007178

-

Making new contacts: the mTOR network in metabolism and signalling crosstalkNature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 15:155–162.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm3757

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

- Version of Record published: March 7, 2017 (version 1)

Copyright

© 2017, Stuttfeld et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,081

- views

-

- 168

- downloads

-

- 1

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Biochemistry and Chemical Biology

- Cell Biology

Hibernation is a period of metabolic suppression utilized by many small and large mammal species to survive during winter periods. As the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms remain incompletely understood, our study aimed to determine whether skeletal muscle myosin and its metabolic efficiency undergo alterations during hibernation to optimize energy utilization. We isolated muscle fibers from small hibernators, Ictidomys tridecemlineatus and Eliomys quercinus and larger hibernators, Ursus arctos and Ursus americanus. We then conducted loaded Mant-ATP chase experiments alongside X-ray diffraction to measure resting myosin dynamics and its ATP demand. In parallel, we performed multiple proteomics analyses. Our results showed a preservation of myosin structure in U. arctos and U. americanus during hibernation, whilst in I. tridecemlineatus and E. quercinus, changes in myosin metabolic states during torpor unexpectedly led to higher levels in energy expenditure of type II, fast-twitch muscle fibers at ambient lab temperatures (20 °C). Upon repeating loaded Mant-ATP chase experiments at 8 °C (near the body temperature of torpid animals), we found that myosin ATP consumption in type II muscle fibers was reduced by 77–107% during torpor compared to active periods. Additionally, we observed Myh2 hyper-phosphorylation during torpor in I. tridecemilineatus, which was predicted to stabilize the myosin molecule. This may act as a potential molecular mechanism mitigating myosin-associated increases in skeletal muscle energy expenditure during periods of torpor in response to cold exposure. Altogether, we demonstrate that resting myosin is altered in hibernating mammals, contributing to significant changes to the ATP consumption of skeletal muscle. Additionally, we observe that it is further altered in response to cold exposure and highlight myosin as a potentially contributor to skeletal muscle non-shivering thermogenesis.

-

- Biochemistry and Chemical Biology

- Neuroscience

In most mammals, conspecific chemosensory communication relies on semiochemical release within complex bodily secretions and subsequent stimulus detection by the vomeronasal organ (VNO). Urine, a rich source of ethologically relevant chemosignals, conveys detailed information about sex, social hierarchy, health, and reproductive state, which becomes accessible to a conspecific via vomeronasal sampling. So far, however, numerous aspects of social chemosignaling along the vomeronasal pathway remain unclear. Moreover, since virtually all research on vomeronasal physiology is based on secretions derived from inbred laboratory mice, it remains uncertain whether such stimuli provide a true representation of potentially more relevant cues found in the wild. Here, we combine a robust low-noise VNO activity assay with comparative molecular profiling of sex- and strain-specific mouse urine samples from two inbred laboratory strains as well as from wild mice. With comprehensive molecular portraits of these secretions, VNO activity analysis now enables us to (i) assess whether and, if so, how much sex/strain-selective ‘raw’ chemical information in urine is accessible via vomeronasal sampling; (ii) identify which chemicals exhibit sufficient discriminatory power to signal an animal’s sex, strain, or both; (iii) determine the extent to which wild mouse secretions are unique; and (iv) analyze whether vomeronasal response profiles differ between strains. We report both sex- and, in particular, strain-selective VNO representations of chemical information. Within the urinary ‘secretome’, both volatile compounds and proteins exhibit sufficient discriminative power to provide sex- and strain-specific molecular fingerprints. While total protein amount is substantially enriched in male urine, females secrete a larger variety at overall comparatively low concentrations. Surprisingly, the molecular spectrum of wild mouse urine does not dramatically exceed that of inbred strains. Finally, vomeronasal response profiles differ between C57BL/6 and BALB/c animals, with particularly disparate representations of female semiochemicals.