Research Culture: Career choices of underrepresented and female postdocs in the biomedical sciences

Figures

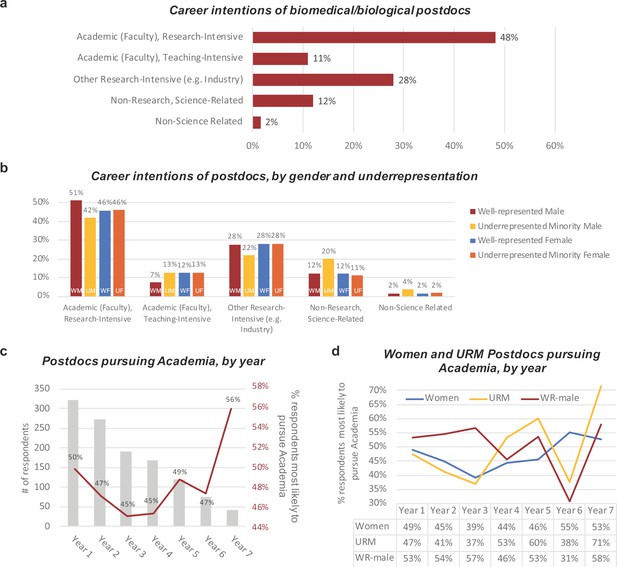

Career intentions of biomedical postdocs.

(a) Percentage of respondents likely to pursue five different career paths. (b) Percentage of respondents likely to pursue these career paths broken down by gender and well-represented/underrepresented minority. Underrepresented minorities include the racial categories of American Indian or Alaska Native, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander and/or the ethnicity of Hispanic or Latino. Well-represented respondents identified as Asian or White and Non-Hispanic or Latino. (c) Percentage of postdocs in years 1 to 7 of their training who are likely to pursue a research position in academia (red line, right vertical axis). The number of survey respondents in each year is represented by the grey bars (left vertical axis). (d) Percentage of women (blue), underrepresented minority (yellow; URM), and well-represented male (red; WR-male) postdocs most likely to pursue a research career in academia in years 1 to 7 of their training (the number of respondents in each category are shown in Figure 1—figure supplement 1a).

-

Figure 1—source data 1

Source data on career intentions of postdocs.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/48774/elife-48774-fig1-data1-v2.xlsx

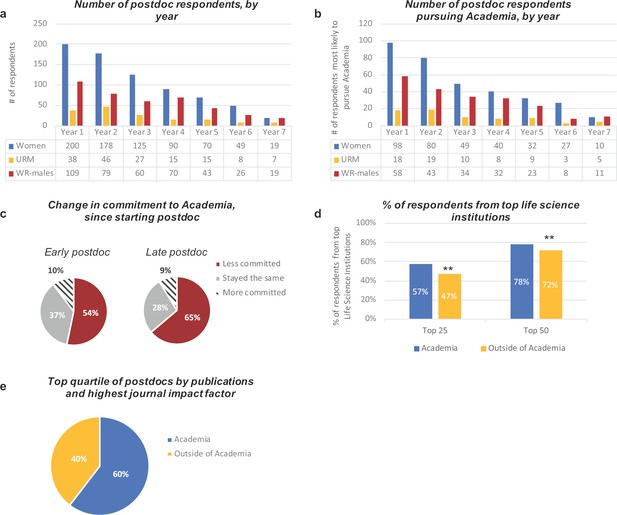

Characteristics of postdoc respondents.

(a) Number of respondents in years 1 to 7 of their training for women (blue), underrepresented minority (yellow; URM), and well-represented male (red; WR-male) postdocs. (b) Number of respondents in years 1 to 7 of their training who are likely to pursue a research position in academia for women (blue), underrepresented minority (yellow; URM), and well-represented male (red; WR-male) postdocs. (c) Respondents were asked to indicate their change in commitment to each career path since starting as a postdoctoral researcher. The change in commitment to academia is shown for early and late postdocs who intend to most likely pursue a nonacademic career. (d) The percentage of academic-bound (blue) and nonacademic-bound (yellow) respondents from top US life science research institutions based on counts of high-quality research outputs from Nature’s Index data from January 1, 2017 to December 31, 2017. **p<0.001 (e) The career interests of respondents whose total publications were greater than or equal to 12 and highest journal impact factor was greater than or equal to 13, representing the top quartile of respondents.

-

Figure 1—figure supplement 1—source data 1

Source data on change in commitment to academia for nonacademic-bound postdocs.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/48774/elife-48774-fig1-figsupp1-data1-v2.xlsx

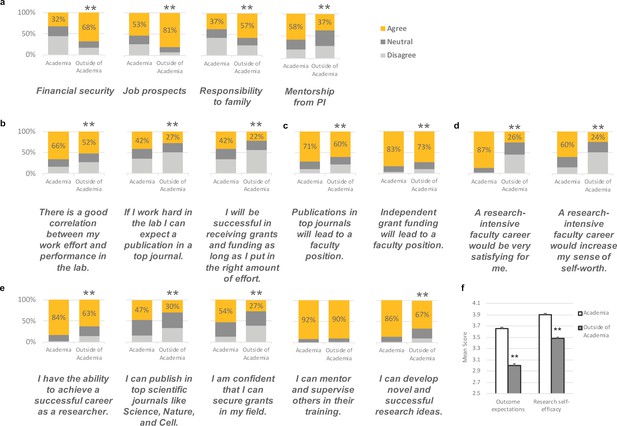

Factors that influence the career choices of postdocs.

Respondents were asked to rate factors that influenced their career choice on a five-point Likert-type scale (strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly agree). For the purpose of the figures, agree represents both strongly agree and agree responses, and disagree represents both strongly disagree and disagree responses. **p<0.001. (a) Factors that showed the greatest difference between postdocs intending to pursue academic research and those who do not. The percent of academic-bound and nonacademic-bound postdocs responding to statements relating to (b) expectancy (will my effort lead to high performance?); (c) instrumentality (will performance lead to desirable outcomes?); (d) valence (do I find the outcomes desirable?); and (e) research self-efficacy. The answers to seven of these questions were then used to calculate scores for outcome expectations (f, left), and the answers to the other five questions were used to calculate scores for research self-efficacy (f, right): in both cases the mean score for academic-bound postdocs (white column) was significantly higher than the mean score for nonacademic-bound postdocs (grey column). Cronbach's alpha was used to assess internal consistency: outcome expectations scale has an alpha of 0.73 (with a 95% CI of 0.71—0.75, p<0.0001), and the research self-efficacy scale has an alpha of 0.79 (with a 95% CI of 0.77—0.81, p<0.0001). See Methods for more information on scale development, construct and content validity.

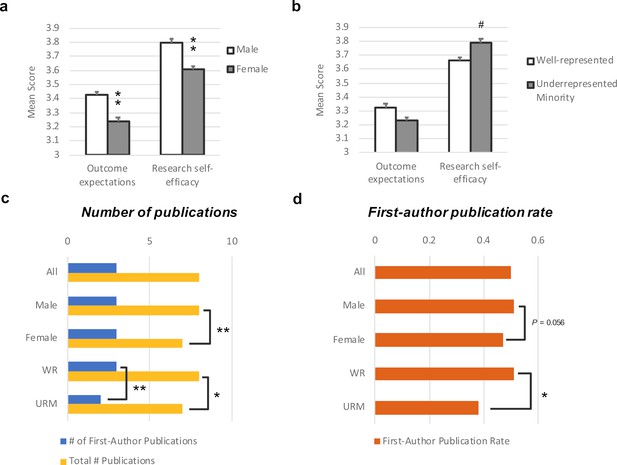

Self-efficacy and publication scores differ depending on gender and representation.

Results of the outcome expectations and self-efficacy scales are compared by (a) gender and (b) well-represented/underrepresented minority respondents. (c) The total number of publications (yellow) and first-author publications (blue). (d) The first-author publication rate (based on the number of years since starting a PhD) for male, female, URM and WR postdocs. URM and WR groups includes both female and male postdocs. **p<0.001, *p<0.01, #p<0.05.

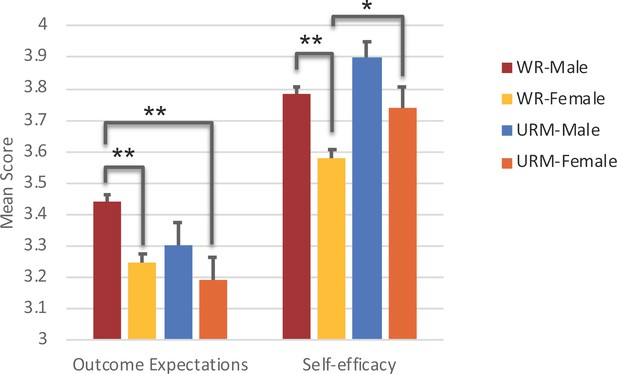

Differences in outcome expectations and research self-efficacy by gender and underrepresentation.

Results of the outcome expectations and research self-efficacy scales are compared for well-represented male (red; WR-Male), well-represented female (yellow; WR-Female), underrepresented minority male (blue; URM-Male), and underrepresented minority female (orange; URM-Female) postdocs. **p<0.001, *p<0.015.

-

Figure 3—figure supplement 1—source data 1

Source data on outcome expectations and research self-efficacy.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/48774/elife-48774-fig3-figsupp1-data1-v2.xlsx

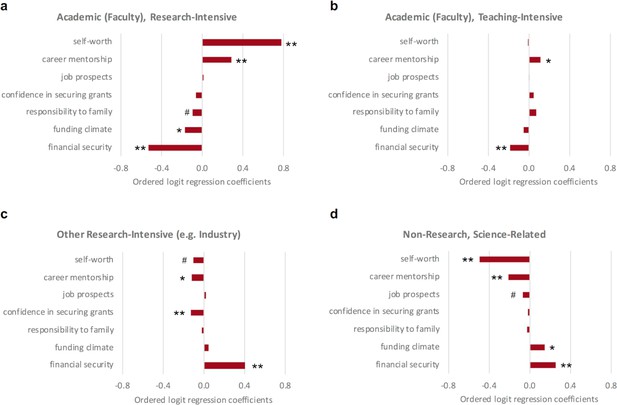

Factors that predict a postdoc’s choice of career.

Ordered logit regression analysis was applied to respondents’ answers to see which factors can predict the career intention of postdocs pursuing (a) research-intensive, (b) academic (faculty), teaching-intensive, (c) other research-intensive (e.g. industry), and (d) non-research, science-related positions. The higher level of self-worth that postdocs have and the more mentorship they receive from their PI, the more likely they are to pursue a research-intensive career in academia; the more that financial security is an influential factor to their career choice, the more likely postdocs will pursue 'other research intensive (e.g., industry)' and 'non-research; science-related' career paths. The results of the analysis are discussed in more detail in the main text. p-values represent whether the factor is significant with respect to the intention (ranging from least likely to most likely) to pursue the career path listed in the figure sub-header. **p<0.001, *p<0.01, #p<0.05.

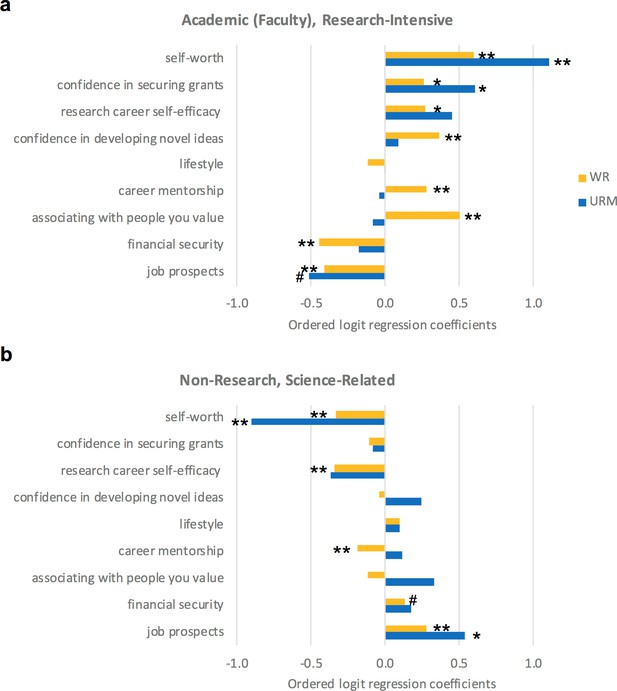

Factors that predict the career choices of underrepresented minority postdocs.

Ordered logit regression analysis of factors that predict the career intentions of well-represented (yellow; WR) and underrepresented (blue; URM) postdocs intending to pursue (a) academic, research-intensive or (b) non-research, science-related careers. Associating with people they value was a strong predictor for WR postdocs choosing to pursue an academic career. Whereas, URM postdocs felt they were less likely to associate with people they value in academia. The results of the analysis are discussed in more detail in the main text. p-values represent whether the factor is significant with respect to the intention (ranging from least likely to most likely) to pursue the career path listed in the figure sub-header. **p<0.001, *p<0.01, #p<0.05.

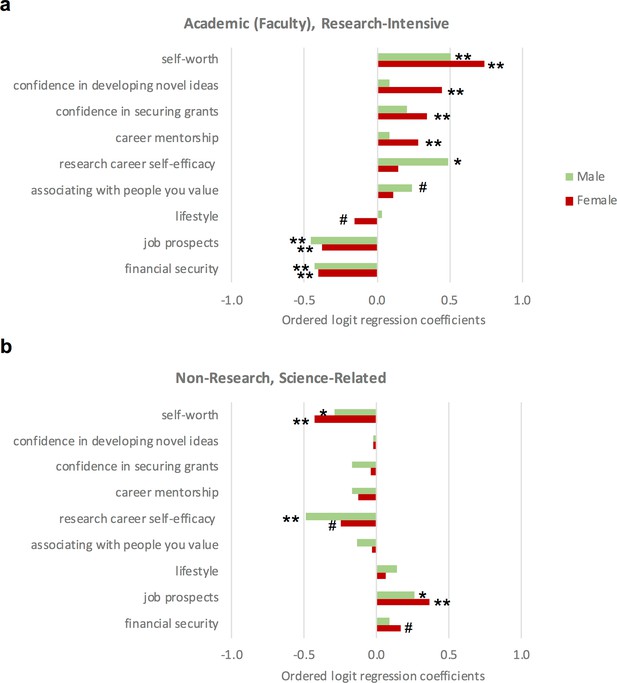

Factors that predict the career intention of male and female postdocs.

Ordered logit regression analysis of factors that predict the career intentions of male (green) and female (red) postdocs intending to pursue (a) academic, research-intensive or (b) non-research, science-related careers. For female postdocs, confidence in developing novel ideas, confidence in securing grants, and career mentorship were stronger predictors for pursing a research-intensive career than for male postdocs. Whereas, female postdocs perceived lifestyle as a negative aspect for pursing a research-intensive career, it was not a predictor for why male postdocs pursue a career in academia. The results of the analysis are discussed in more detail in the main text. p-values represent whether the factor is significant with respect to the intention (ranging from least likely to most likely) to pursue the career path listed in the figure sub-header. **p<0.001, *p<0.01, #p<0.05.

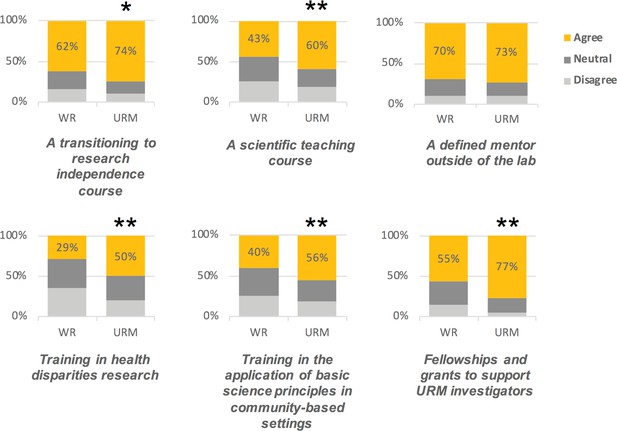

Underrepresented minorities seek additional and more specialized training.

Respondents were asked whether the following factors would increase their likelihood of pursuing a research career in academia. For the purpose of the figures, 'agree' represents an aggregate of 'strongly agree' and 'agree' responses, and 'disagree' represents an aggregate of 'strongly disagree' and 'disagree' responses. URM respondents indicated that receiving more specialized courses, and support outside of the laboratory would make them more likely to pursue academic research careers.**p<0.001, *p<0.01.

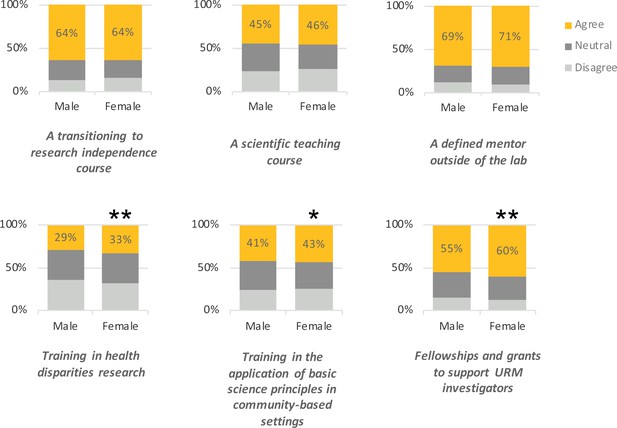

Male and female perceptions of specialized training and support.

Respondents were asked whether the following factors would increase their likelihood of pursuing a research career in academia. For the purpose of the figures, 'agree' represents an aggregate of 'strongly agree' and 'agree' responses, and 'disagree' represents an aggregate of 'strongly disagree' and 'disagree' responses. Similar to male postdocs, over 50% of female respondents indicated that a specialized course in research independence, and more mentorship outside of the laboratory would make them more likely to pursue academic research careers. **p<0.001, *p<0.01.

Tables

Percentage of PhDs and postdocs who enter academic positions.

| Population | Outcome | Year(s) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomedical PhDs who enter academia (research/teaching) | 43% | 2012 | (Biomedical Research Workforce Working Group, 2012) |

| Biomedical PhDs who enter tenure-track | 23% | 2012 | (Biomedical Research Workforce Working Group, 2012) |

| Life Science PhDs who enter tenure-track within 5 years | 8.1% | 2015 | (National Science Foundation, 2018) |

| Biomedical Postdocs who enter tenure-track | 27.4% | 1980–2003 | (Kahn and Ginther, 2017) |

| Biomedical Postdocs who enter tenure-track | 21% | 2013 | (Kahn and Ginther, 2017) |

| UCSF Postdocs who enter faculty positions | 37% | 2000–2013 | (Silva et al., 2016) |

Median number of publications, publication rates, and journal impact factors by career-intention, gender, and underrepresentation.

Survey participants were asked to report the total number of publications in which they are listed as an author, the total number of first-author publications, and the highest impact factor of the journals in which they have published. First-author publication rate was calculated by dividing the number of first-author publications by the number of years since they started their PhD. Median values with the interquartile range are shown. **p<0.001, *p<0.01, #p<0.05.

| Total no. of publications N = 1282 | No. of first-author publications N = 1282 | First-author publication rate N = 1270 | Highest impact factor N = 1275 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 8.0 [5.0;12.0] | 3.0 [2.0;5.0] | 0.50 [0.27;0.82] | 8.50 [4.94;13.2] | 1284 |

| Academic-bound | 9.0 [5.0;13.0] | 4.0 [2.0;6.0] | 0.56 [0.33;1.01] | 8.90 [4.90;14.0] | 595 |

| Nonacademic-bound | 7.0 [4.0;10.0]** | 3.0 [2.0;4.0]** | 0.42 [0.23;0.68]** | 8.29 [4.95;12.1] | 657 |

| Male | 8.0 [5.0;13.0] | 3.0 [2.0;6.0] | 0.51 [0.29;0.92] | 9.10 [5.00;13.9] | 485 |

| Female | 7.0 [5.0;11.0]** | 3.0 [2.0;5.0] | 0.47 [0.26;0.77] | 8.20 [4.72;12.8]# | 774 |

| Well-represented | 8.0 [5.0;12.0] | 3.0 [2.0;5.0] | 0.51 [0.29;0.85] | 8.82 [4.97;13.5] | 1110 |

| Underrepresented Minority | 7.0 [4.0;10.0]* | 2.0 [2.0;4.0]** | 0.38 [0.22;0.70]* | 6.57 [4.80;12.0]# | 174 |

Research self-efficacy predicts publications for women and URM postdocs.

Incidence rate ratios (IRR) of first-author publications and relative mean change of first-author publication rates were calculated for respondents who identified as female or underrepresented minority (n = 1,211). The incident rate ratio (IRR) represents the change in the dependent variable in terms of a percentage increase or decrease, with the precise percentage determined by the amount the IRR is either above or below 1. In the pooled sample the IRR for female vs. male (URM vs. WR) is 0.87 (0.82), so there is a 13% (18%) decrease in the first author publications for females vs, males (URM vs. WR). Conversely, there was a 15% increase in the first author publications for every addition point on the self-efficacy scale. The relative mean change gives the percent increase (or decrease) in the response for every one-unit increase in the independent variable. In the pooled sample the percent decrease of first author publication rate for female vs. male (URM vs. WR) is 5% (20%). Conversely, there was a 21% increase in the first author publication rate for every addition point on the self-efficacy scale. Incidence rate ratios or relative mean change of research self-efficacy by subgroups of those identifying as male (n = 463), female (n = 748), well-represented (WR; n = 1,043) and underrepresented minority (URM; n = 168) were also calculated (last four rows of the table). All four subgroups showed a similar increase in the two dependent variables with respect to self-efficacy.

| First-author publications | First-author publication rate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR | 95% CI | p-value | Mean Change | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Pooled Sample | ||||||

| Female vs. Male | 0.87 | 0.81, 0.94 | 0.001 | 0.95 | 0.84, 1.07 | 0.27 |

| URM vs. WR | 0.82 | 0.73, 0.91 | 0.001 | 0.80 | 0.67, 0.95 | 0.012 |

| Research self-efficacy | 1.15 | 1.09, 1.21 | 0.000 | 1.21 | 1.13, 1.31 | 0.000 |

| Subgroups | ||||||

| Research self-efficacy for men only | 1.20 | 1.09, 1.31 | 0.000 | 1.23 | 1.08, 1.42 | 0.002 |

| Research self-efficacy for women only | 1.12 | 1.05, 1.19 | 0.001 | 1.21 | 1.09, 1.32 | 0.000 |

| Research self-efficacy for WR only | 1.15 | 1.09, 1.23 | 0.000 | 1.23 | 1.17, 1.31 | 0.000 |

| Research self-efficacy for URM only | 1.11 | 0.95, 1.28 | 0.196 | 1.22 | 1, 1.49 | 0.048 |

Additional files

-

Supplementary file 1

Survey questionnaire.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/48774/elife-48774-supp1-v2.pdf

-

Supplementary file 2

Top US life science research institutions and number of respondents by institution.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/48774/elife-48774-supp2-v2.xlsx

-

Transparent reporting form

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/48774/elife-48774-transrepform-v2.pdf