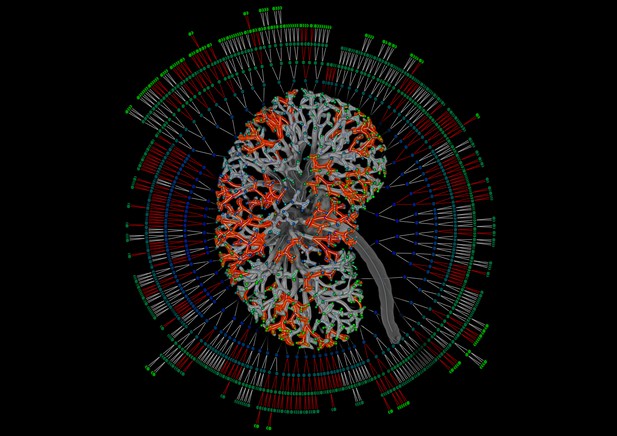

Image credit: Short et al. (CC BY 4.0)

During development and before birth, many organs develop from branched tubes. Whether forming the airways of the lungs, the collecting ducts of the kidneys or the milk ducts of the breast, there are many similarities between these structures. Given their shared tree-like structures, one possibility is that these tissues all form through the same general process.

A key challenge is understanding why branched networks develop and pattern in such a way as to assume their functional roles in the adult organ. A unifying theory, which proposes that certain tips stop growing in a random manner, has been proposed to solve this problem. In this theory, the branched mammary gland structures stop growing when the tips of the structure impinge on neighbouring branches. In the kidney, this cessation has been proposed to occur when nephrons – the structures that filter urine from blood – form near the end of the collecting ducts.

By growing kidneys in the laboratory and studying developing kidneys in mice, Short et al. investigated whether nephrons do affect collecting duct growth and branch development. The results of these experiments instead suggest that nephron formation has no effect on duct growth or branching. The nephrons also do not appear to affect how quickly the duct cells grow and divide. Moreover, there is no evidence that the cell proliferation in individual branch tips ceases randomly by any other mechanism.

Overall, the experiments Short et al. performed suggest that a unifying theory of branching in developing organs may not hold true, at least not in the way that has been envisioned previously.