Image credit: Vuolo et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Almost all cells in the human body are covered in tiny hair-like structures known as primary cilia. These structures act as antennae to receive signals from outside the cell that regulate how the body grows and develops. The cell has to deliver new proteins and other molecules to precise locations within its cilia to ensure that they work properly. Each cilium is separated from the rest of the cell by a selective barrier known as the transition zone, which controls the movement of molecules to and from the rest of the cell.

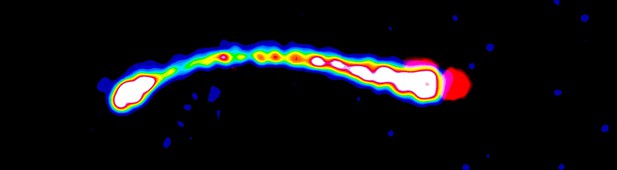

Dynein-2 is a motor protein that moves other proteins and cell materials within cilia. It includes two subunits known as WDR34 and WDR60. The genes that produce these subunits are mutated in Jeune and short rib polydactyly syndromes that primarily affect how the skeleton forms. However, little is known about the roles the individual subunits play within the motor protein.

Vuolo et al. used a gene editing technique called CRISPR-Cas9 to remove one or both of the genes encoding the dynein-2 subunits from human cells. The experiments show that the two subunits have very different roles in cilia. WDR34 is required for cells to build a cilium whereas WDR60 is not. Instead, WDR60 is needed to move proteins and other materials within an established cilium. Unexpectedly, the experiments suggest that dynein-2 is also required to maintain the transition zone.

This work provides the foundations for future studies on the role of dynein-2 in building and maintaining the structure of cilia. This could ultimately help to develop new treatments to reduce the symptoms of Jeune syndrome and other diseases caused by defects in cilia.