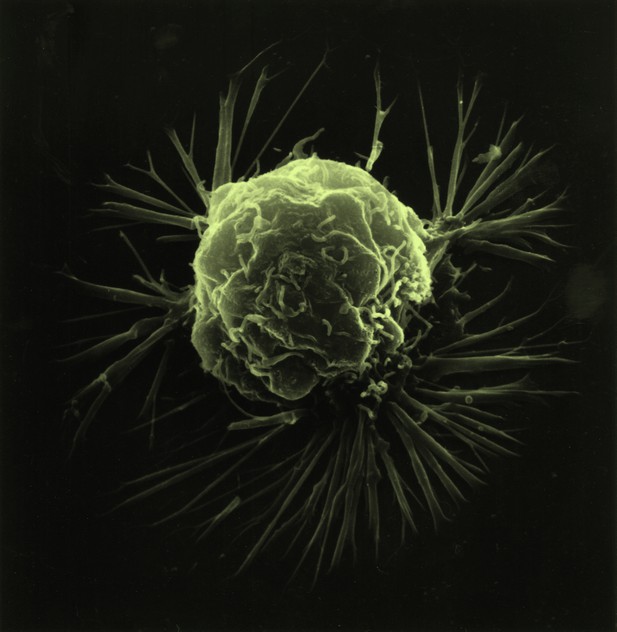

Cancer cells, such as this breast cancer cell, can travel in the body and create new tumors. Image credit: Public domain

Cancers develop when cells in the body divide rapidly in an uncontroled manner. It is generally possible to cure cancers that remain contained within a small area. However, if the tumor cells start to move, the cancer may spread in the body and become life threatening. Currently, most of the anti-cancer treatments act to reduce the multiplication of these cells, but not their ability to migrate.

A signal protein called Ras stimulates human cells to grow and move around. In healthy cells, the activity of Ras is tightly controled to ensure cells only divide and migrate at particular times, but in roughly 30% of all human cancers, Ras is abnormally active. Ras switches on another protein, named RalB, which is also involved in inappropriate cell migration. Yet, it is not clear how RalB is capable to help Ras trigger the migration of cells.

Zago et al. used an approach called optogenetics to specifically activate the RalB protein in human cells using a laser that produces blue light. When activated, the light-controlled RalB started abnormal cell migration; this was used to dissect which molecules and mechanisms were involved in the process.

Taken together, the experiments showed that, first, Ras ‘turns on’ RalB by changing the location of two proteins that control RalB. Then, the activated RalB regulates the exocyst, a group of proteins that travel within the cell. In turn, the exocyst recruits another group of proteins, named the Wave complex, which is part of the molecular motor required for cells to migrate.

Zago et al. also found that, in patients, the RalB protein was present at abnormally high levels in samples of breast cancer cells that had migrated to another part of the body. Overall, these findings indicate that the role of RalB protein in human cancers is larger than previously thought, and they highlight a new pathway that could be a target for new anti-cancer drugs.