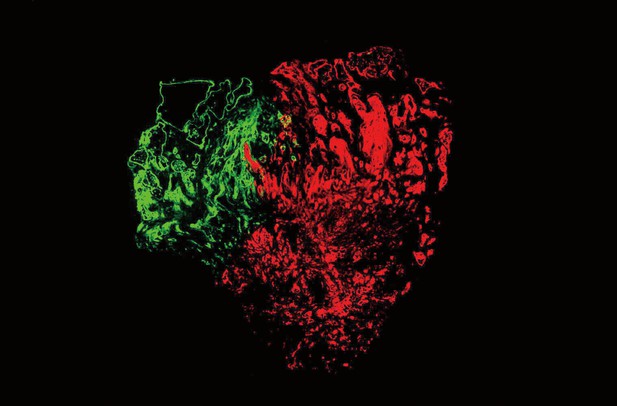

Difference in growth between cancer cells that are aggressive (red) and cancer cells that have been converted back to the early stage subtype (green) of bladder cancer. Image credit: SungEun Kim (CC BY 4.0)

In order to grow, cancer cells shut down or over-activate genes that normally maintain a cell’s health. The Sonic Hedgehog gene – named after a Japanese cartoon character – is associated with the cancer of several tissues, including the bladder. In 2014, researchers found that losing the Sonic Hedgehog gene, Shh for short, is necessary for bladder cancers to become aggressive: Shh signals prompt healthy cells near the tumor to inhibit the cancer cell growth, whilst aggressive bladder cancer cells turn off the Shh gene. Kim et al. – including many of the researchers involved in the 2014 work – now investigate how cancer cells switch off the Shh gene and what effect it has on bladder cancer cells and their surrounding tissue when turned back on.

DNA sequencing bladder cancer cells derived from human patients showed that there were no genetic deletions or mutations within the gene. However, the sequence and nearby regions of DNA did contain methylations – a chemical modification that generally switches genes off. When mice with early stages of bladder cancer were treated with a drug that inhibits methylation, the Shh gene turned back on, the bladder cancers stopped growing and the tumors stayed at an early stage of development. When the same drug was used on mice with aggressive bladder cancer, this caused non-cancer cells in the surrounding tissue to respond to Shh and send restraining signals back to the tumor. These signals eventually stopped cancer growth and converted the tumor into a less aggressive type of bladder cancer. Additionally, Kim et al. saw that blocking methylation had the same effect on human bladder cancer cells that had been transplanted into mice.

These results therefore indicate that Shh could be a new target for cancer treatments. For instance, drugs that decrease methylation and turn on the gene could be a way of managing cancer in patients with aggressive bladder cancers, which often show low activity of the gene. However, future studies are needed to understand what exactly happens within cancer cells during tumor conversion and to determine if this kind of intervention could have unintended consequences.