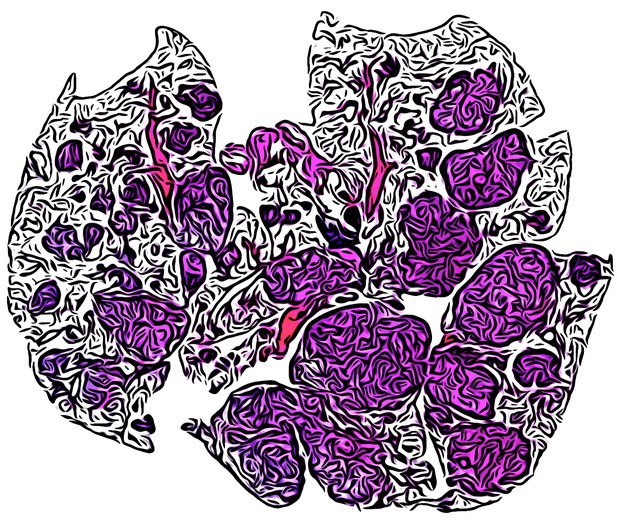

Graphical representation of a microscopy image taken from Kang et al. of a mouse lung with tumors. Image credit: Jodi Kmiec (CC BY 4.0)

Cancers form in humans and other animals when cells of the body develop mutations that allow them to grow and divide uncontrollably. The set of chemical reactions happening inside cancer cells, referred to as “metabolism”, can be very different to metabolism in the healthy cells they originate from. Some of these differences are directly caused by mutations, while others are a result of the environment surrounding the cancer cells as they develop into a tumor.

A protein called NRF2 is often overactive in human tumors due to mutations in its inhibitor protein KEAP1. Previous studies have shown that NRF2 changes the metabolism of cancer cells by switching specific genes on or off. However, since cancer cells also have other mutations that could mask or amplify some of the effects of NRF2, the precise role of this protein in metabolism remains unclear.

To address this question, Kang et al. generated mice that could switch between producing the normal KEAP1 protein or a mutant version that is unable to inhibit NRF2. The mouse model was then used to examine the immediate effects of activating the NRF2 protein. This revealed that NRF2 altered how mouse cells used a molecule called cysteine, which is required to make proteins and other cell components. When NRF2 was active, some of the cysteine molecules were converted into two wasteful and toxic particles by an enzyme called CDO1.

Kang et al. found that inactivating CDO1 in human lung cancer cells prevented these wasteful particles from being produced. This allows cancer cells to grow more rapidly, and may explain why human tumors generally evolve to shut down CDO1.

The findings of Kang et al. show that not all of the changes in metabolism caused by individual mutations in cancer cells help tumors to grow. As a tumor develops it may need to acquire further mutations to override the negative effects of these changes in metabolism. In the future these findings may help researchers develop new therapies that reactivate or mimic CDO1 to limit the growth of tumors.