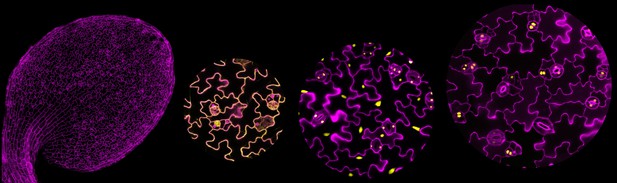

A young Arabidopsis leaf (left) with cell outlines in purple and close-ups of the localization of the TurboID protein (yellow) in different cell types. Image credit: Andrea Mair and Yan Gong (CC BY 4.0)

Cells contain thousands of different proteins that work together to control processes essential for life. To fully understand how these processes work it is important to know which proteins interact with each other, and which proteins are present at specific times or in certain cellular locations. Investigating this is particularly difficult if the proteins of interest are rare, either because they are present only at low levels or because they are unique to a particular type of cell.

One such protein known as FAMA is only found in young guard cells in plants. Guard cells are rare cells that surround pores on the surface of leaves. They help open or close the pores to allow carbon dioxide and water in and out of the plant. Inside these cells, FAMA regulates the activity of genes in the nucleus, the compartment in the cell that houses the plant’s DNA.

Two recently developed molecular biology tools, called TurboID and miniTurbo, allow researchers to identify proteins that are in close contact with a protein of interest or are present at a specific place inside living animal cells. These tools use a modified enzyme to add a small chemical tag to proteins that are close to it, or anything to which it is anchored. Mair et al. adapted these tools for use in plants and tested their utility in two species that are commonly used in research: a tobacco relative called Nicotiana benthamiana, and the thale cress Arabidopsis thaliana.

Their experiments showed that TurboID and miniTurbo can be used to tag proteins in different types of plant cells and organs, as well as at different stages of the plants’ lives. To test whether the tools are suitable for identifying partners of rare proteins, Mair et al. used FAMA as their protein of interest. Using TurboID, they detected several proteins in close proximity to FAMA, including some that FAMA was not previously known to interact with. Mair et al. also found that TurboID could identify a number of proteins that were present in the nuclei of guard cells. This shows that the tool can be used to detect proteins in sub-compartments of rare plant cell types.

Taken together, these findings show that TurboID and miniTurbo may be customized to study plant protein interactions and to explore local protein ‘neighborhoods’, even for rare proteins or specific cell types. To enable other plant biology researchers to easily access the TurboID and miniTurbo toolset developed in this work, it has been added to the non-profit molecular biology repository Addgene.