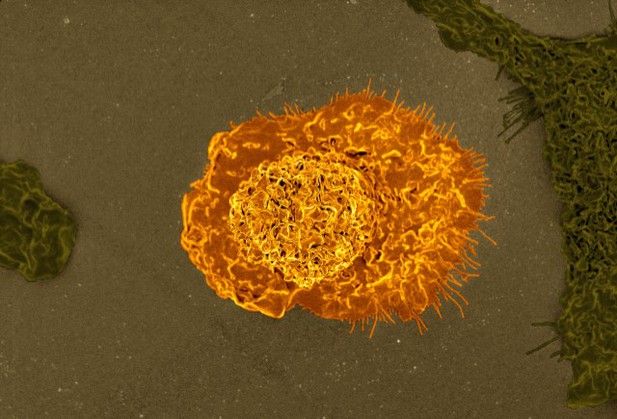

Microscopy image of a macrophage. Image credit: NIAID (CC BY 2.0)

Although inflammation can be good for the body and help fight off infection, in certain cases it can also be harmful. When immune cells switch on at the wrong time, they can cause damage to cells and tissues. Fat tissue has its own population of immune cells called adipose tissue macrophages that remove dead fat cells and keep the tissue working. However, obesity changes the behaviour of these macrophages so they switch on as though they were fighting an infection and make the fat tissue inflamed. The signals produced by these activated macrophages stop fat tissue working, and this can lead to type 2 diabetes.

The trigger that activates macrophages in obesity is not yet clear, but some evidence suggests that it is due to the type of fat available. Fats come in two main forms: saturated, which can lead to high cholesterol, or unsaturated which can reduce the risk of high blood pressure. An increase in saturated fats can cause cells, including macrophages, to become stressed.

Researchers showed in 2011 that macrophages in the fatty tissue of obese mice accumulate fat and become inflamed, but it was unclear which types of fat, if any, were driving the inflammation.

Now, Petkevicius et al. – including some of the researchers involved in the 2011 work – report that macrophages in the fatty tissue of obese mice make excess phosphatidylcholine, a fat normally found in the cell membrane. Phosphatidylcholine is a type of fat known as a phospholipid and it is made up of two subunits called fatty acids that can either be saturated or unsaturated. In obese people and mice, fatty tissue produces too much of the enzyme that makes phosphatidylcholine, called CCTa.

Petkevicius et al. showed that partially removing the CCTa gene from macrophages reduces inflammation, but, unexpectedly, the amount of phosphatidylcholine in the cells stays the same. This is because macrophages respond to the halt in phosphatidylcholine production by removing less of the phospholipid from the membrane. This gives the macrophages time to exchange the saturated fatty acids in phosphatidylcholine for unsaturated fatty acids. Therefore, the longer phosphatidylcholine stays in the membrane, the more likely it is to contain unsaturated fatty acids. Further experiments demonstrated that this change counteracts the effects caused by excess saturated fats, protecting the cells and reducing inflammation.

Although the understanding of obesity is still in its early stages, this study adds another piece of the puzzle. If we can understand why fat stops working in obesity, and how this leads to disease, it could aid the design of new treatments for type 2 diabetes.