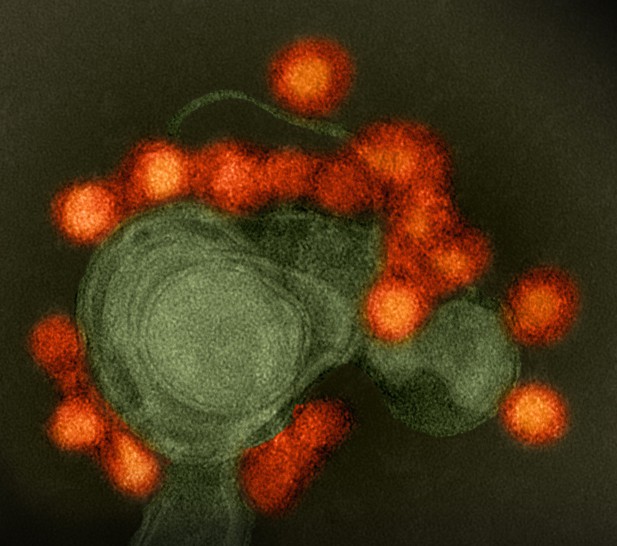

Zika virus (red). Image credit: Adapted from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Since the Zika virus first emerged in the Pacific Islands in 2007, it has caused many outbreaks in the Pacific and Latin America. Some scientists thought that after exposure to the virus people would develop long-term immunity to it, reducing the number of outbreaks in the future. Several studies supported this idea. These studies showed that many people recently infected with Zika developed antibodies in their blood that might protect them from becoming ill during future outbreaks. But it was not clear how long this protection would last.

To better understand how immunity to the Zika virus changes over time, Henderson, Aubry et al. combined data from eight surveys that collected blood samples at different time points during Zika outbreaks in French Polynesia and Fiji. The analysis showed that the proportion of people with detectable antibodies against the Zika virus increased in both countries after the outbreaks. In children these immune responses persisted for years, but antibody levels declined over time in adults. By contrast, antibodies to the closely related dengue virus did not wane over time in individuals tested for both viruses in Fiji in 2013, 2015 and 2017.

The data suggest that immunity against the Zika virus may not last as long as previously thought, which could affect the chances of future outbreaks. The findings may also have implications for researchers studying the virus, because the number of people with antibodies against the virus is not a good estimate of how many people were initially infected. More studies are needed to understand immunity to Zika virus over time and how it may affect future outbreaks.