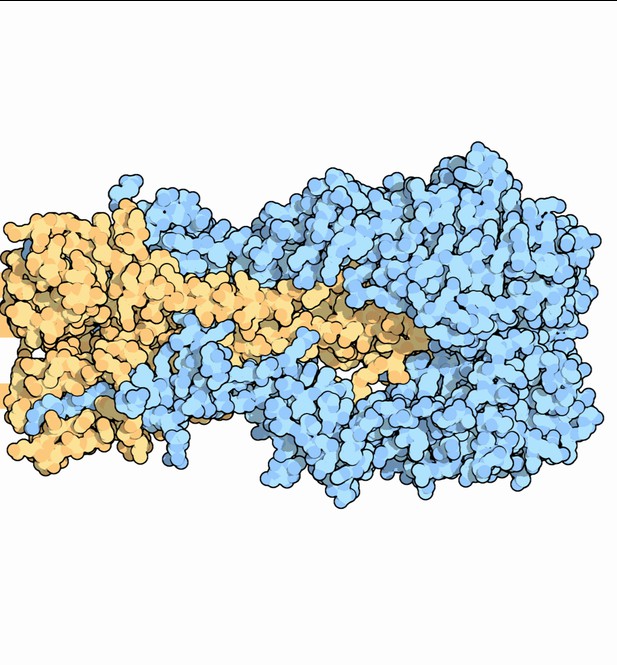

The human immune system makes different anti-flu antibodies that can recognize the hemagglutinin protein (blue and yellow) found on the virus’ surface, targeting it for destruction. Image credit: Modified from David S Goodsell and the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank (RCSB PDB) (CC BY 4.0)

The human immune system protects the body from repeat attacks by remembering past infections. However, a typical person comes down with the flu every five to seven years. This is because flu viruses rapidly evolve to bypass our defenses. So, after a few years, the viruses look so different that the immune system no longer recognizes them.

The immune system recognizes flu viruses by producing proteins known as antibodies, which can bind to the virus and prevent it from infecting cells. Many of these antibodies bind to a protein on the surface of the virus called hemagglutinin, but each anti-flu antibody recognizes only a small region of the protein. This means that to escape recognition by a single antibody, all the virus needs to do is wait for a lucky mutation to change the part of hemagglutinin recognized by that antibody. But humans make many different antibodies. To escape them all, flu viruses would need lots of lucky mutations. So how do flu viruses keep winning the evolutionary lottery?

To answer this question, Lee et al. made all the possible individual mutations to the hemagglutinin protein of a human flu virus. A pool of these viruses was then exposed to the full mix of antibodies present in human serum (the liquid component of blood). Lee et al. then checked which mutations helped the virus survive contact with the antibodies. For most human serum samples, a single mutation was enough to allow the virus to escape most of one person’s anti-flu antibodies. This suggests that the immune response to flu is so focused on a small region of hemagglutinin that a mutation in this region can enable the virus to take a huge step towards evading immune detection.

Even more surprising was what happened when Lee et al. looked at serum from different people. A mutation that helped the virus to escape immune detection in one person often had little or no effect on escape from another person’s immunity. In other words, the lucky mutation that the virus needed to escape differed from one person to the next.

Every year there are many related flu viruses that infect humans. The results of Lee et al. suggest that people could be susceptible to different forms of the virus. Understanding how flu viruses escape immune detection in different people could help us identify which version of the virus different people are more susceptible to, and perhaps eventually better predict how the virus will evolve and spread.