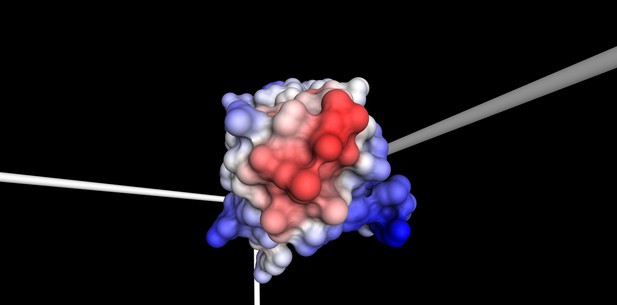

Surface of the disease-causing antibody light chain domain with ‘water-hating’, hydrophobic regions in red, and ‘water-loving’, hydrophilic regions in blue. Pamina Kazman (CC BY 4.0)

Amyloid light chain amyloidosis, shortened to AL amyloidosis, is a rare and often fatal disease. It is caused by a disorder of the bone marrow. Usually, cells in the bone marrow produce Y-shaped proteins called antibodies to fight infections. In AL amyloidosis, these cells release too much of the short arm of the antibody, known as its light chain, and the light chains also carry mutations. The antibodies are no longer able to assemble properly, and instead misfold and form structures, known as amyloid fibrils. The fibrils build up outside the cells, gradually causing damage to tissues and organs that can lead to life-threatening organ failure.

Due to the rareness of the disease, diagnosis is often overlooked and delayed. People experience widely varying symptoms, depending on the organs affected. Also, given the diversity of antibodies people make, every person with AL amyloidosis has a variety of mutations implicated in their disease. It is thought that mutations in the antibody light chain make it unstable and prone to misfolding, but it remains unclear which specific mutations trigger a cascade of amyloid fibril formation.

Now, Kazman et al. have pinpointed the exact mechanism in one case of the disease. First, tissue biopsies from a woman with advanced AL amyloidosis were analyzed, and the defunct antibody light chain was isolated. Eleven mutations were identified in the antibody light chain, only one of which was found to be responsible for the formation of the harmful fibrils. The next step was to determine how this one small change was so damaging. The experiments showed that after the antibody light chain was cut in two, a process that happens naturally in the body, this single mutation transforms it into a protein capable of causing disease.

In this ‘bedside to lab bench’ study, Kazman et al. have succeeded in determining the molecular origin of one case of AL amyloidosis. The results have also shown that the instability of antibodies due to mutation does not alone explain the formation of amyloid fibrils in this disease and that the cutting of this protein in two is also important. It is hoped that, in the long run, this work will lead to new diagnostics and treatment options for people with AL amyloidosis.