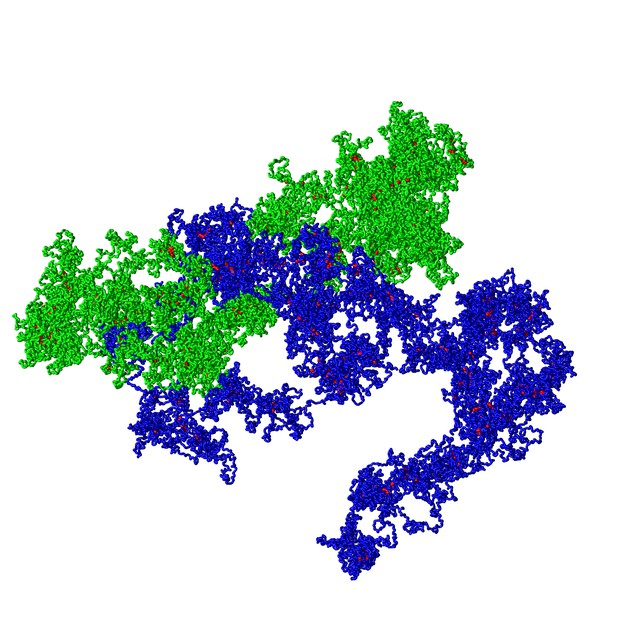

A duplicated chromosome (one copy shown in blue and another in green) before cell division, with one-sided loop extruding complexes shown in red. Image credit: Edward J. Banigan (CC BY 4.0)

The different molecules of DNA in a cell are called chromosomes, and they change shape dramatically when cells divide. Ordinarily, chromosomes are packaged by proteins called histones to make thick fibres called chromatin. Chromatin fibres are further folded into a sparse collection of loops. These loops are important not only to make genetic material fit inside a cell, but also to make distant regions of the chromosomes interact with each other, which is important to regulate gene activities. The fibres compact to prepare for cell division: they fold into a much denser series of loops. This is a remarkable physical feat in which tiny protein machines wrangle lengthy strands of DNA.

A process called loop extrusion could explain how chromatin folding works. In this process, ring-like protein complexes known as SMC complexes would act as motors that can form loops. SMC complexes could bind a chromatin fibre and reel it in to form the loops, with the density of loops increasing before cell division to further compact the chromosomes. Looping by SMC complexes has been observed in a variety of cell types, including mammalian and bacterial cells. From these studies, loop extrusion is generally assumed to be ‘two-sided’. This means that each SMC complex reels in the chromatin on both sides of it, thus growing the chromatin loop.

However, imaging individual SMC complexes bound to single molecules of DNA showed that extrusion can be asymmetric, or ‘one-sided’. These observations show the SMC complex remains anchored in place and the chromatin is reeled in and extruded by only one side of the complex. So Banigan, van den Berg, Brandão et al. created a computer model to test whether the mechanism of one-sided extrusion could produce chromosomes that are organised, compact, and ready for cell division, like two-sided extrusion can.

To answer this question, Banigan, van den Berg, Brandão et al. analysed imaging experiments and data that had been collected using a technique that captures how chromatin fibres are arranged inside cells. This was paired with computer simulations of chromosomes bound by SMC protein complexes. The simulations and analysis found that the simplest one-sided loop extrusion complexes generally cannot reproduce the same patterns of chromatin loops as two-sided complexes. However, a few specific variations of one-sided extrusion can actually recapitulate correct chromatin folding and organisation.

These results show that some aspects of chromosome organization can be attained by one-sided extrusion, but many require two-sided extrusion. Banigan, van den Berg, Brandão et al. explain how the simulated mechanisms of loop extrusion could be consistent with seemingly contradictory observations from different sets of experiments. Altogether, they demonstrate that loop extrusion is a viable general mechanism to explain chromatin organisation, and that it likely possesses physical capabilities that have yet to be observed experimentally.