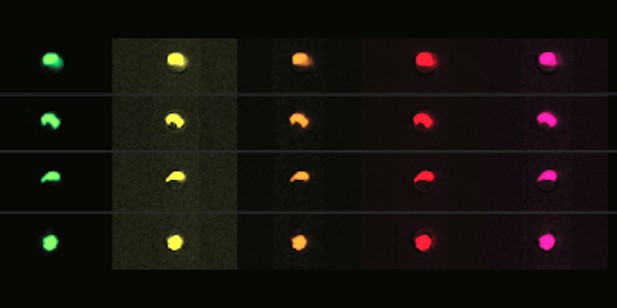

Autofluorescence-positive microglia from 10-month-old mice emitting light of a range of different colors. Image credit: Burns et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Microglia are a unique type of immune cell found in the brain and spinal cord. Their job is to support neurons, defend against invading microbes, clear debris and remove dying neurons by engulfing them. Despite these diverse roles, scientists have long believed that there is only a single type of microglial cell, which adapts to perform whatever task is required. But more recent evidence suggests that this is not the whole story.

Burns et al. now show that we can distinguish two subtypes of microglia based on a property called autofluorescence. This is the tendency of cells and tissues to emit light of one color after they have absorbed light of another. Burns et al. show that about 70% of microglia in healthy mouse and monkey brains display autofluorescence. However, about 30% of microglia show no autofluorescence at all. This suggests that there are two subtypes of microglia: autofluorescence-positive and autofluorescence-negative.

But does this difference have any implications for how the microglia behave? Autofluorescence occurs because specific substances inside the cells absorb light. In the case of microglia, electron microscopy revealed that autofluorescence was caused by structures within the cell called lysosomal storage bodies accumulating certain materials. The stored material included fat molecules, cholesterol crystals and other substances that are typical of disorders that affect these compartments. Burns et al. show that autofluorescent microglia contain larger amounts of proteins involved in storing and digesting waste materials than their non-autofluorescent counterparts. Moreover, as the brain ages, lysosomal storage material builds up inside autofluorescent microglia, which increase their autofluorescence as a result. Unfortunately, this accumulation of cellular debris also makes it harder for the microglia to perform their tasks.

Increasing evidence suggests that the accumulation of waste materials inside the brain contributes to diseases of aging. Future work should examine how autofluorescent microglia behave in animal models of neurodegenerative diseases. If these cells do help protect the brain from the effects of aging, targeting them could be a new strategy for treating aging-related diseases.