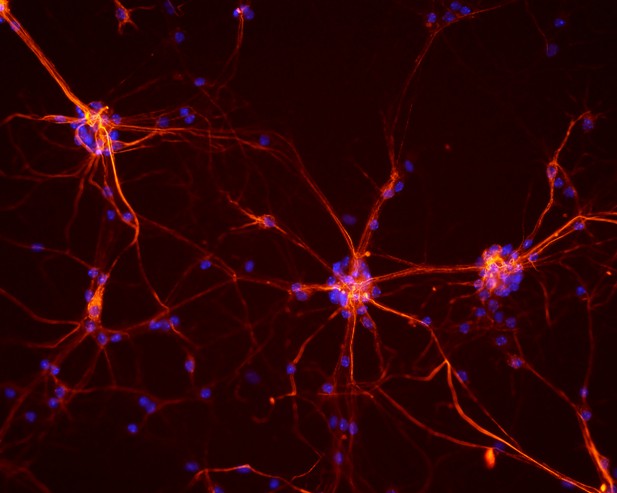

Three connected mouse neurons. Image credit: NICHD (CC BY 2.0)

How the brain stores information is a question that has fascinated neuroscientists for well over a century. Two general ideas have emerged. The first is that groups of neurons hold information by staying active. The second is that they hold information by strengthening their connections to one another, making it easier for them to work together in the future. Scientists call this second idea 'long-term potentiation'.

One of the molecules involved in long-term potentiation is a protein called calcium-calmodulin-dependent kinase II, or CaMKII for short. Blocking CaMKII, or deleting its gene, stops the connections between neurons from becoming stronger. This suggests neurons need CaMKII to learn, but it remains unclear whether neurons also use CaMKII to maintain neuronal memories after they have been created. If CaMKII does play a role in maintaining memories, blocking it after learning should reverse the learning process, but so far, experiments have not been able to show this.

Tao et al. revisited these experiments to find out more. They examined slices of brain tissue from mice that had been treated with fast-acting CaMKII inhibitors. It took tens of minutes, but the inhibitors were able to reverse long-term potentiation, both for newly acquired neuronal memories and for older memories that had formed when the mice were alive. The choice of CaMKII inhibitor and the time lag could explain why scientists have not observed the effect before.

Understanding long-term potentiation is a fundamental part of understanding learning and memory. It could also reveal more about the opposite phenomenon: long-term depression. This is a type of learning where the connections between neurons become weaker. Long-term depression also takes tens of minutes to occur, suggesting that future research into CaMKII might shed light on how it works.