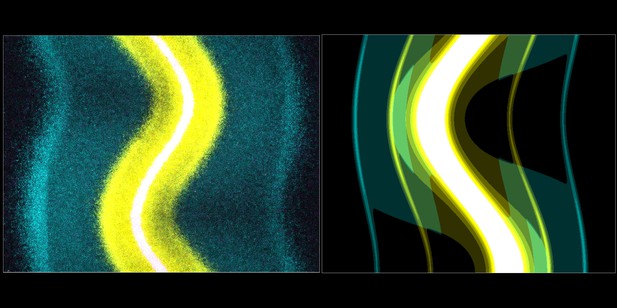

Experimental (left) and simulation (right) images showing a migrating bacterial population chemotactically smoothing itself from a wiggly shape to a straight line across three different time points (shown in white, yellow and blue). Image credit: Left image, Tapomoy Bhattacharjee; Right image, Daniel B. Amchin (CC BY 4.0)

Flocks of birds, schools of fish and herds of animals are all good examples of collective migration, where individuals co-ordinate their behavior to improve survival. This process also happens on a cellular level; for example, when bacteria consume a nutrient in their surroundings, they will collectively move to an area with a higher concentration of food via a process known as chemotaxis.

Several studies have examined how disturbing collective migration can cause populations to fall apart. However, little is known about how groups withstand these interferences. To investigate, Bhattacharjee, Amchin, Alert et al. studied bacteria called Escherichia coli as they moved through a gel towards nutrients.

The E. coli were injected into the gel using a three-dimensional printer, which deposited the bacteria into a wiggly shape that forces the cells apart, making it harder for them to move as a collective group. However, as the bacteria migrated through the gel, they smoothed out the line and gradually made it straighter so they could continue to travel together over longer distances.

Computer simulations revealed that this smoothing process is achieved by differences in how the cells respond to local nutrient levels based on their position. Bacteria towards the front of the group are exposed to more nutrients, causing them to become oversaturated and respond less effectively to the nutrient gradient. As a result, they move more slowly, allowing the cells behind them to eventually catch-up.

These findings reveal a general mechanism in which limitations in how individuals sense and respond to an external signal (in this case local nutrient concentrations) allows them to continue migrating together. This mechanism may apply to other systems that migrate via chemotaxis, as well as groups whose movement is directed by different external factors, such as temperature and light intensity.