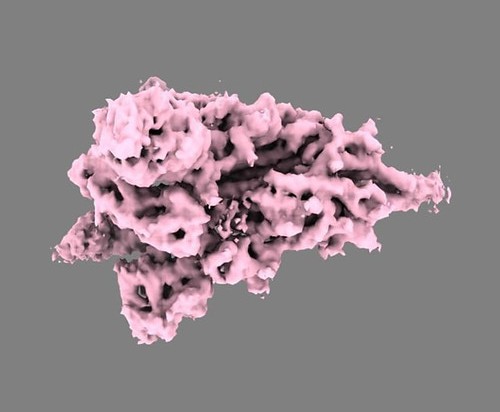

SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Image credit: Public domain

When SARS-CoV-2 – the virus that causes COVID-19 – infects our bodies, our immune system reacts by producing small molecules called antibodies that stick to a part of the virus called the spike protein. Vaccines are thought to work by triggering the production of similar antibodies without causing disease. Some of the most effective antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 bind a specific area of the spike protein called the ‘receptor binding domain’ or RBD.

When SARS-CoV-2 evolves it creates a challenge for our immune system: mutations, which are changes in the virus’s genetic code, can alter the shape of its spike protein, meaning that existing antibodies may no longer bind to it as effectively. This lowers the protection offered by past infection or vaccination, which makes it harder to tackle the pandemic.

As it stands, it is not clear which mutations to the virus’s genetic code can affect antibody binding, especially to portions outside the RBD. To complicate things further, the antibodies people produce in response to mild infection, severe infection, and vaccination, while somewhat overlapping, exhibit some differences. Studying these differences could help minimize emergence of mutations that allow the virus to ‘escape’ the antibody response.

A phage display library is a laboratory technique in which phages (viruses that infect bacteria) are used as a ‘repository’ for DNA fragments that code for a specific protein. The phages can then produce the protein (or fragments of it), and if the protein fragments bind to a target, it can be easily detected. Garrett, Galloway et al. exploited this technique to study how different portions of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein were bound by antibodies. They made a phage library in which each phage encoded a portion of the spike protein with different mutations, and then exposed the different versions of the protein to antibodies from people who had experienced prior infection, vaccination, or both.

The experiment showed that antibodies produced during severe infection or after vaccination bound to similar parts of the spike protein, while antibodies from people who had experienced mild infection targeted fewer areas. Garrett, Galloway et al. also found that mutations that affected the binding of antibodies produced after vaccination were more consistent than mutations that interfered with antibodies produced during infection.

While these results show which mutations are most likely to help the virus escape existing antibodies, this does not mean that the virus will necessarily evolve in that direction. Indeed, some of the mutations may be impossible for the virus to acquire because they interfere with the virus’s ability to spread. Further studies could focus on revealing which of the mutations detected by Garrett, Galloway et al. are most likely to occur, to guide vaccine development in that direction. To help with this, Garrett, Galloway et al. have made the data accessible to other scientists and the public using a web tool.