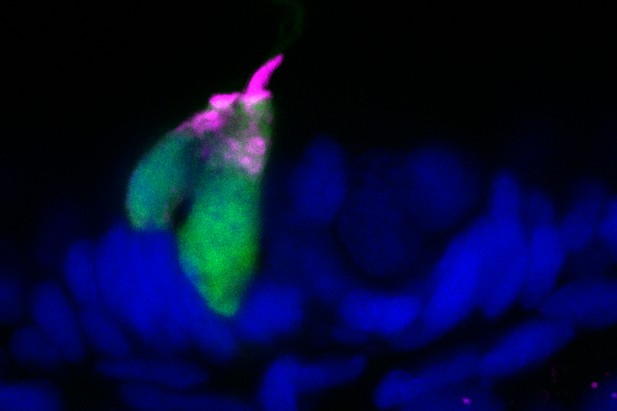

Microscopy image showing where the protein (magenta) coded by the minar2 gene is localized in zebrafish hair cells (green). Image credit: Gao et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Cholesterol is present in every cell of the body. While it is best known for its role in heart health, it also plays a major role in hearing, with changes in cholesterol levels negatively affecting this sense. To convert sound waves into electrical brain signals, specialised ear cells rely on hair-like structures which can move with vibrations; cholesterol is present within these hair ‘bundles’, but its exact role remains unknown.

Genetic studies have identified over 120 genes essential for normal hearing. Animal data suggest there may be many more – including, potentially, some which control cholesterol. For instance, in mice, loss of the Minar2 gene causes profound deafness. Yet exactly which role the protein that Minar2 codes for plays in the ear remains unknown. This is in part because that protein does not resemble any other related proteins, making it difficult to infer its function.

To find out more, Gao et al. investigated loss of minar2 in zebrafish, showing that deleting the gene induced deafness in the animals. Without minar2, the hair bundles in ear cells were longer, thinner, and less able to sense vibrations: cholesterol could not move into these structures, causing them to dysfunction. Exposing the animals to drugs that lower or raise cholesterol levels respectively worsened or improved their hearing abilities.

A recent study revealed that mutations in MINAR2 also cause deafness in humans. The findings by Gao et al. highlight the need for further research which explores the role of cholesterol and MINAR2 in hair bundle function, as this may potentially uncover cholesterol-based treatments for hearing problems.