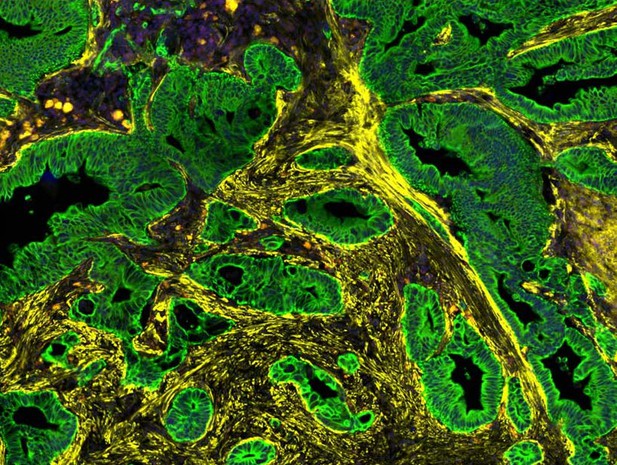

Pancreatic cancer (green) surrounded by cancer-associated fibroblasts (yellow). Image credit: Croft et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Pancreatic cancer is one of the deadliest and most difficult cancers to treat. It responds poorly to immunotherapy for instance, despite this approach often succeeding in enlisting immune cells to fight tumours in other organs. This may be due, in part, to a type of cell called fibroblasts. Not only do these wrap pancreatic tumours in a dense, protective layer, they also foster complex relationships with the cancerous cells: some fibroblasts may fuel tumour growth, while other may help to contain its spread.

These different roles may be linked to spatial location, with fibroblasts adopting different profiles depending on their proximity with cancer calls. For example, certain fibroblasts close to the tumour resemble the myofibroblasts present in healing wounds, while those at the periphery show signs of being involved in inflammation. Being able to specifically eliminate pro-cancer fibroblasts requires a better understanding of the factors that shape the role of these cells, and how to identify them.

To examine this problem, Croft et al. relied on tumour samples obtained from pancreatic cancer patients. They mapped out the location of individual fibroblasts in the vicinity of the tumour and analysed their gene activity. These experiments helped to reveal the characteristics of different populations of fibroblasts. For example, they showed that the myofibroblast-like cells closest to the tumour exhibited signs of oxygen deprivation; they also produced podoplanin, a protein known to promote cancer progression. In contrast, cells further from the cancer produced more immune-related proteins.

Combining these data with information obtained from patients’ clinical records, Croft et al. found that samples from individuals with worse survival outcomes often featured higher levels of podoplanin and hypoxia. Inflammatory markers, however, were more likely to be present in individuals with good outcomes.

Overall, these findings could help to develop ways to selectively target fibroblasts that support the growth of pancreatic cancer. Weakening these cells could in turn make the tumour accessible to immune cells, and more vulnerable to immunotherapies.