At the end of June, eLife started a trial of a new peer-review process designed to give authors more control over the decision to publish. In brief, once the editors had decided that a manuscript should undergo in-depth peer review, the journal was committed to publishing the article along with the decision letter from the editor, the separate peer reviews from the referees, and the response to the reviews from the author (see “Peer review: eLife trials a new approach” and “A new twist on peer review”). Authors were able to opt in to the trial at the submission stage.

The trial has been closed for new submissions since August 8, and we have published more than ten of the first articles from the trial. This blog post reports data on the first part of the process: that is, the decision to reject a paper before in-depth review or to send it for peer review (which is tantamount to accepting it for publication, unless the authors decide not to proceed after receiving the reviews). Overall, almost a third of authors opted in to the new approach: the success rates for male and female last authors in the trial were similar, although late-career last authors fared better than their early- and mid-career colleagues.

Interest in the trial

In the 43 days in which the trial was open, 313 authors opted in to the trial process (32%), compared with 665 who submitted into the regular process. For the purposes of evaluating the success of the trial, we compare the outcomes of the 313 trial submissions with the 665 regular submissions received during the same period of time. Note that the regular submissions do not represent a perfect control group: the trial was not randomised and we do not know whether there are differences in the quality of submissions between the two groups.

During the trial, we contacted all authors shortly after submission to find out why they had or had not opted in. Out of 109 responses (of which 32 were from authors who opted in and 77 were from authors who did not), various reasons that affected the decision to opt in were cited. The most common reasons for opting in related to the efficiency of the process, support for innovation, and support for transparency.

The most common reason for not participating was not noticing the option to opt in in the first place (40 of 77 responses). Seven authors raised concerns that the editors might reject a higher proportion of the trial submissions and two authors were concerned about the separate reviews being published in full. Other concerns relate to the trial process potentially taking longer, while others did not fully understand how the trial process would work.

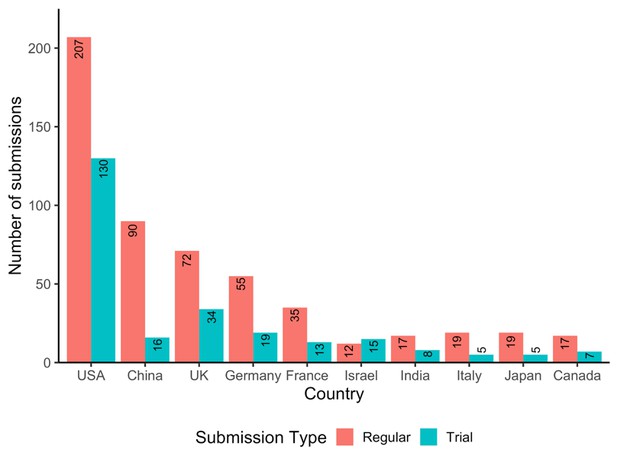

Based on the affiliation of the last author, the ten countries from which most submissions were received are shown in Figure 1. In the trial process, 41.5% of submissions were from last authors based in the United States (compared with 31.1% for regular submissions), while 5.1% of trial submissions were from authors based in China (compared with 13.5% for regular submissions). For other countries, there was little difference in terms of the trial’s popularity: for example, last authors from the UK represented 10.9% of trial submissions and 10.8% of regular ones; last authors from Germany represented 6.1% of trial submissions and 8.3% of regular ones; and last authors from France represented 4.2% of trial submissions and 5.3% of regular ones. This suggests that the trial process may be more popular in some countries (such as the United States) and less popular with authors from others (such as China), while for others there is little difference.

Figure 1. Origin of submissions, based on the country of the last author. The text in each bar indicates the number of initial submissions from the ten countries from which most submissions were received, for both regular and trial submissions.

As the countries of origin differ between the two groups, and because we would expect the proportion of papers sent for in-depth review to vary by country (e.g., see Murray et al [preprint]), we have to use caution in interpreting the differences between the two groups in the results that follow.

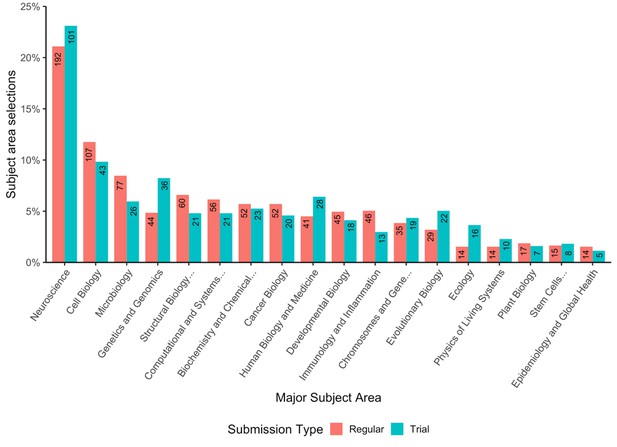

The number of submissions to each of the 18 subject areas that eLife uses to categorize content are shown in Figure 2; note that authors can select one or two subject areas during submission. The distribution among the subject areas was similar for trial and regular submissions. Neuroscience was most likely to feature as a submission’s subject area for both trial (23.1%) and regular (21.1%) submissions.

Figure 2. Subject areas of trial and regular submissions. The text in each bar indicates the number of times each subject area was selected by the authors within each submission type. The names of the subject areas ending in ellipses have been truncated.

Effects on the triage rate

Prior to appeals, 65 out of 313 trial submissions and 192 out of 665 regular submissions were sent for in-depth review. After appeals are taken into account, 70 manuscripts submitted into the trial (22.4%) were selected by the editors for in-depth peer review, while 197 out of 665 regular submissions (29.6%) during the same period moved forward with in-depth peer review. A chi-square test of independence indicates that this difference is significant (X2 (degrees of freedom (DF)=1, N=978) = 7.28, p=0.007). If we assume that all the submissions that were sent out for in-depth peer review are published, the acceptance rate for the trial would be ~22%, which would be higher than the current acceptance rate for regular submissions (~15%), but lower than the percentage of regular submissions that are sent out for in-depth peer review (~29%).

There are various reasons why the proportion of submissions encouraged for review (the "encouragement rate") for trial submissions was lower than the regular submissions over the same period of time. Indeed, since the first decision (whether or not to review in depth) is more likely to determine whether a manuscript is published in the trial process, editors may be more cautious about that initial decision, and they may be less inclined to move ahead with submissions that they might otherwise have given the benefit of the doubt (since in the regular process, those papers could still be rejected after peer review).

Appeals

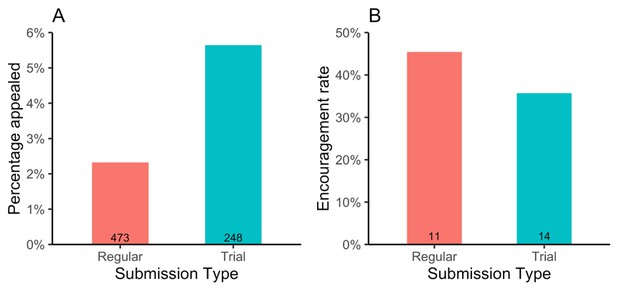

Because the path to publication for authors is clearer if they can pass the initial editorial evaluation, and because editors would naturally be cautious while evaluating submissions within the trial process, it was reasonable to suspect that a higher proportion of negative trial decisions would be appealed. Figure 3A shows there was indeed a significant difference, with 5.6% of reject decisions appealed in the trial, but only 2.1% of rejection decisions were appealed for the regular submissions. Although the sample size of appealed submissions is too small to draw firm conclusions, Figure 3B suggests that the success rate of appeals was broadly similar for trial and regular submissions.

Figure 3. Percentage of decisions appealed and their outcome.

A) Percentage of rejection decisions that were formally appealed for trial and regular submissions. A chi-square test of independence indicates that this is a significant difference, with 5.6% of reject decisions appealed in the trial, but only 2.1% of rejection decisions appealed for the regular submissions (X2 (DF=1, N = 24) = 5.33, p=0.021). In the trial, 14 authors appealed, out of 248 reject decisions. For the regular submissions, 11 authors appealed, out of 472 reject decisions. B) Percentage of appeals that were successful for both trial and regular submissions. In the trial, 5 out of 14 appeals were successful. For the regular submissions, 5 out of 11 appeals were successful. Text at the base of each bar indicates (A) the number of rejected initial submissions of each submission type and (B) the number of appeals that were received.

Again, these results will need to be evaluated within the context of the complete process. Whereas we might anticipate a small number of trial authors wanting to withdraw their work after peer review, there will not be any trial papers rejected after peer review by the editors. For regular submissions, there will inevitably be rejections after peer review that are appealed, and we will report those results in due course.

Gender and career stage

Here we consider the outcome of submissions based on the gender of the last author. We were not able to determine the gender of the last author for 0.64% of trial submissions and 3.8% of regular submissions.

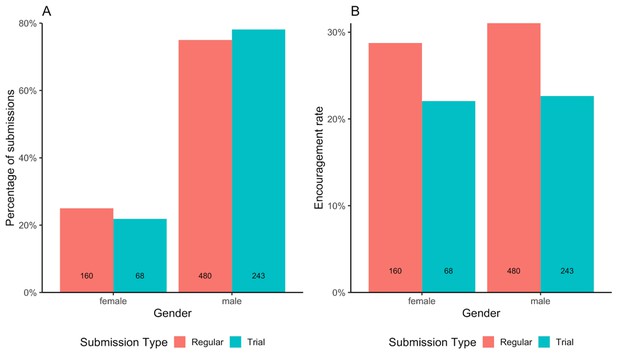

Figure 4A suggests that male last authors were more likely to opt in to the trial process (78.1% compared with 75% for regular submissions), but female last authors were less likely to participate (21.9% compared with 25% for regular submissions). However, Figure 4B indicates that the percentage of submissions to the trial that were sent for in-depth peer review was similar for male and female last authors (22.6% and 22.1% respectively); the difference is more noticeable for regular submissions (31% for male last authors and 28.8% for female last authors).

Figure 4. A) Proportion of submissions by gender and B) the percentage of submissions reviewed by gender of the last author. The submissions for which gender could not be assigned are not included in these analyses. The text at the base of each bar indicates the number of initial submissions with female and male last authors for each submission type.

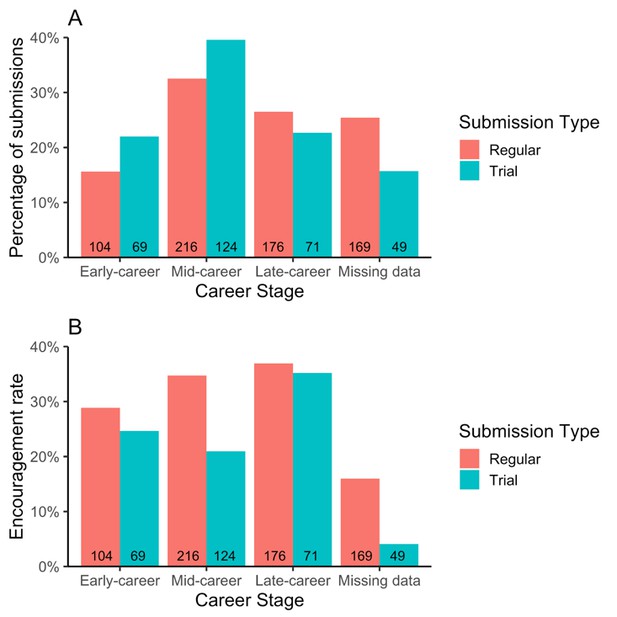

To examine the encouragement rate by career stage of the last author, we determined the year the last author became an independent researcher, using their lab page biography or CV as far as possible, and using their title as a guide for independence (e.g., using “Assistant Professor” for US-based authors). We then grouped the submissions as coming from an early-career lab (for this purpose meaning the last author had been independent for 5 years or less); from a mid-career lab (in this case meaning the last author had been independent for 6-15 years); or from a late-career lab (meaning the last author had been independent for more than 15 years). It is important to note that a reasonably high proportion of the submissions could not be classified in terms of the career stage of the final author (16% for the trial articles and 25% for the regular submissions), and this may skew the results. Last authors based in China account for most of the missing career-stage data (44 regular submissions and five trial submissions). This may account for the lower trial opt-in rates for the authors with missing career stage data (Figure 5A), as last authors based in China were less likely to opt in to the trial overall (Figure 1).

Figure 5. A) Percentage of authors who chose to participate in the trial by career stage and B) the encouragement rate by career stage of the last author. Text at the base of each bar indicates the number of initial submissions by career stage and submission type.

If we assume that the submissions with missing data were evenly distributed between early, mid- and late-career researchers, early-career last authors were most likely to submit their paper as part of the trial (40% of early-career researchers chose the trial option) and late-career last authors were the least likely (29% chose the trial option). Further details are shown in Figure 5A. However, submissions with late-stage researchers as the last author were more likely to be encouraged for in-depth review compared with submissions with early-career and mid-career researchers as the last author: this is true for both trial and regular submissions (Figure 5B). The reduction in encouragement rate for the trial versus the regular process is particularly marked for early- and mid-career last authors: the difference in encouragement rate was -7.1% for early-career last authors, -14.9% for mid-career last authors, and just -1.4% for late-career last authors. However, these interpretations have to be considered tentative given the relatively high levels of missing career-stage data.

Time to first decision

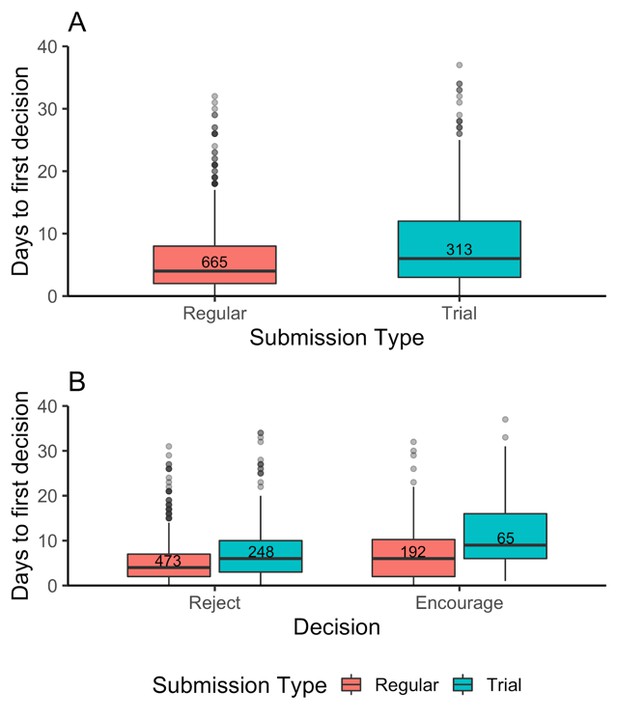

For trial submissions, because the initial editorial evaluation is effectively a decision to publish the article, it was reasonable to anticipate that those decisions may take longer. Indeed, Figure 6A shows that the median time to a decision for trial submissions was 6 days (IQR = 3–12 days), whereas for regular submissions this was 4 days (IQR = 2–8 days). When the outcome is taken into account, the median time to rejection was 6 days for trial submissions (IQR = 3–10 days) and 4 days for regular submissions (IQR = 2–7 days). Figure 6B shows that in the trial, the median time to encouragement for review was 9 days (IQR = 6–16 days) and for regular submissions that was 6 days (IQR = 2–10 days).

We see positive decisions taking longer because in most cases a Reviewing Editor would need to assess the work and agree to handle it through the review process, whereas rejections before review may on occasions be completed by a Senior Editor alone.

Figure 6. Time to decision for initial submissions (trial and regular submissions).

A) Overall times to the first decision (before peer review) for trial and regular submissions. B) Time to encourage and time to reject before review for both trial and regular submissions. In both panels, dots indicate outliers. The text within each boxplot displays (A) the number of initial submissions for each submission type and (B) the number of initial submissions for each submission type and decision outcome.

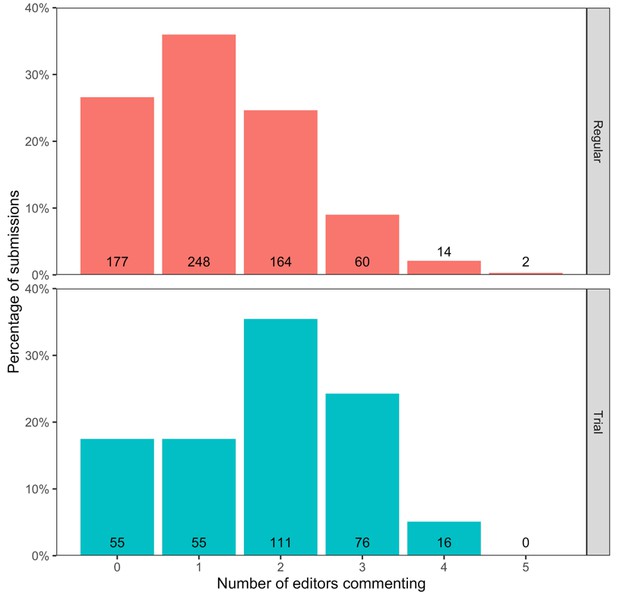

Figure 7 shows there are more editors involved, per paper, in the initial decision for trial submissions compared to regular ones, which helps to explain why the initial decision for trial papers took slightly longer. More specifically, two or more editors beyond the handling editor contributed substantive comments to the initial decision for 65% of the trial submissions. To determine the level of input into the initial decision, staff manually looked through the records to determine how many editors (Senior Editors, Reviewing Editors, and/or external experts if applicable) provided substantive comments on the work (for clarity, this is not showing the number of editors invited or the total number of comments). Responses such as "conflict of interest", "too busy to comment", and "I agree" were not recorded, but comments such as "I agree with him/her because..." were recorded.

Figure 7. Number of editors (including external experts) offering substantive comments to the handling editor on whether or not a submission should be reviewed in-depth, for both regular and trial submissions over the same time period. The number of submissions receiving input from 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 editors is shown within (or above) the bars.

Summary

Although most of the articles that have been peer reviewed in the trial have not been published yet, it is clear that the encouragement rate was lower than it is for regular submissions, and that the initial decision time took longer. Neither finding is surprising given the increased importance that is placed on the initial decision, and that this is a new process where outcomes are uncertain. However, if the majority of the trial submissions invited for peer review are published (rather than being withdrawn by the authors), the overall acceptance rate will be substantially higher for the trial submissions.

The most concerning result in the trial so far is that late-career last researchers appear to be more successful than their early- and mid-career colleagues in passing the initial evaluation into peer review. Although still tentative at this stage (because of missing data) these results will require careful consideration and suggest that modifications in the process will be required to ensure that less well-established researchers in particular are not disadvantaged in any way. It is also noteworthy that the trial process appears to be much less popular in some countries, including China, which is another finding that requires further examination.

There is much more work to be done: we still need to collect the views of authors, editors, and reviewers once the remaining papers have been reviewed, revised, and re-evaluated. In future blog posts, we will report on the following questions:

- How long did peer review take in the trial process?

- Are reviewers more likely to agree or decline to review in the trial?

- How long did author revisions take?

- What proportion of trial papers ended up being published?

- What proportion of published trial papers addressed all the concerns of the reviewers (as judged by the Reviewing Editor)?

- What proportion of the papers selected for peer review in the trial end up being published with minor or major concerns remaining?

In the meantime, we welcome feedback and ideas around how we and others might build on the findings of the trial process so far.

For the latest updates on the peer review trial and other news from eLife, sign up to receive our bi-monthly newsletter. You can also follow @eLife on Twitter.