After two and a half years as a postdoc in the United States, Gal Haimovich moved back to Israel to the Weizmann Institute in 2014, to continue his postdoc project there. His son was born in 2005, when Gal was working in industry as a research associate, while his daughter was born during his PhD at the Technion in 2008.

Gal and his family at a visit to Niagra Falls, a few weeks before Miri and the kids returned to Israel. Image courtesy of Gal Haimovich.

How did you become both a parent and a scientist?

After completing my bachelors in biology I served three years in the army, as most Israelis do. I then did my masters and began a PhD program at the Weizmann Institute. For all this time I was single and I divided my time between research and my hobby: science fiction. Only at the age of 27 did I meet Miri, who became my wife a year later. Miri is kind and funny; she is loving and very supportive. She is also disabled. It is difficult for her to walk and she suffers from chronic pain. This makes everything more challenging.

A month after we got married, my supervisor decided to terminate my PhD. This was a major low point in my career. But Miri lifted me up and within two weeks I was fortunate to find a job in industry as a research associate. Less than a year later, my son, Peleg, was born. Several months passed and I became bored with the routine work and lack of imagination in industry. There was also no chance of promotion since I did not complete my PhD. I wanted to return to academia but was afraid no one would want someone with half a PhD. But with Miri’s encouragement, I made the move. I returned to academia and joined Motti Choder’s lab at the Technion as a PhD candidate. Motti was very supportive, and is an optimist by nature. Working with him was so much better than with my previous mentor, which made my PhD very successful. My daughter, Keshet, was born during my PhD, a month before my first presentation in an international meeting. Leaving her and leaving my wife with a small child and month old baby was not easy. But it was the first of many times that Miri showed me that despite her disability she can handle everything on her own.

After my PhD, we then moved to New York for my postdoctoral research in Rob Singer’s lab at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. I went by myself for a few months before my family then joined me there. This period alone allowed me to acclimatize to the new lab, and get everything ready for my family when they arrived. Nevertheless, moving was difficult for my wife and kids. Again, I was fortunate to work with a supportive mentor who helped me a lot – both financially and otherwise. Still, life in New York was not easy. Some bad luck with my son’s teacher, along with financial difficulties and my wife’s total dependence on me to get out of the house (because she did not have her disabled-accustomed car) made it too difficult. After one year Miri and my kids returned to Israel. I stayed in Rob’s lab for another year with visits home every couple of months.

Although Miri maintained a firm grip on the household and the kids, the separation was difficult for all of us. So I returned to Israel, and found a place at Jeff Gerst’s lab at the Weizmann Institute. Jeff was willing (actually excited) to accept me with my research. The work was finally published a few months ago, and I am now applying for faculty positions in Israel. My hope is to get the “dream job” that provides some stability for my family.

What support have you received as a parent and a scientist?

Except from my wife (obviously), the best support that I got was from our family. Our parents continue to provide a lot of financial support because a postdoc fellowship and disability pension is just not enough. Our families also provide help with the kids (e.g. after school they go to my brother-in-law, where they have lunch and do their homework.)

I also found it very important to have supportive and understanding mentors: people who do not frown when you leave early (or don’t come in at all) due to a sick kid or a school activity. There was little institutional support and no specific support from Israel except for allowed “leave days” to take care of sick kids. At the time my kids were born, there was no paternal leave, only maternal leave (though the situation has now slightly changed).

What for you has been the most difficult aspect of balancing parenthood and science?

Being absent from home for long periods of time during my postdoc, or when going to meetings. Having to balance time between family and lab, sometimes cancelling experiments due to unexpected family issues, or not cancelling experiments and leaving my wife to take care of everything on her own. Having to work late hours, and missing out with the kids at bedtime when they were younger. Nowadays, long hours at the lab means that I can only help them with their homework (in particular math and science) either late at night or over the weekend.

What more could be done to improve the lives of scientist parents? And what single change would have the biggest impact on you?

More money, for sure! It is difficult to get by on grad student or postdoc fellowships. Which is why I took other jobs in parallel (e.g. writing popular science, teaching as many courses as I could, translating articles for students who struggle with their English). All this extra work takes time away from lab work and family time, but the experience gained is valuable.

Again, I think that mentors need to understand that science is not the only thing in your life. I am entitled to dedicate time for my kids, whether its for a teacher parent meeting, taking care of a sick kid (or spouse), or even for something fun.

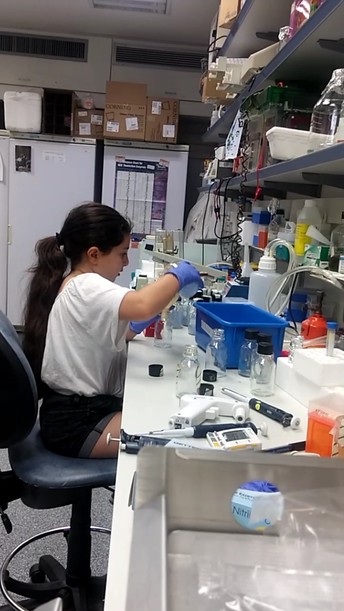

Keshet helping Gal at the lab at Weizmann. Image credit: Gal Haimovich.

How do you think being a scientist with kids compares to working in another profession as a parent?

Its greatest advantage is the flexibility of your schedule in academia, compared to most other places. Another great advantage, if you get it, is tenure: job stability gives stability to your family.

It's a cool and always interesting job; the kids are excited when they visit you in the lab.

There are also disadvantages: low pay at the early career stages of grad student and postdoc (which can last until your late 30s); instability before tenure; having no fixed hours of work also means that there is no true routine to follow which is hard for the kids. Last, the requirement (at least in Israel) to move to another country for your postdoc if you want to eventually become a tenured faculty member can be very difficult for the whole family.

What advice would you give to other scientists who are thinking of having children?

Before joining a lab, ask other students and postdocs if the supervisor is supportive of their family needs or not. You should also see that you get enough funding, or can rely on your extended family for support. Check with your institution whether you are entitled for paid maternity/paternity leave. If not, ask your mentor if he or she can pay, at least a partial stipend. In general – don’t be shy to talk with your mentor about financial issues – even when just applying for a position in the lab. Supportive mentors will find a way to help you.