This post is part of the Innovator Stories Series. At eLife Innovation, we are constantly amazed by open-science ideas and prototypes, but perhaps even more so, we are continuously inspired by the open-source community: its talents, creativity and generosity. In bringing into focus the people behind the projects, we hope that you too will be inspired to make a difference.

By Emmy Tsang

Like many others, Michèle Nuijten, Assistant Professor at Tilburg University, the Netherlands, was initially driven to pursue a bachelor's degree in psychology by her interest in understanding why we do what we do, and the underpinnings of psychological disorders. Soon after she started, however, she was drawn to the study of psychological methods and statistics: how we know what we know.

Around the time she finished her bachelor’s degree, the replication crisis erupted: Dutch professor Diederik Stapel was found to have made up data in at least 54 scientific articles, and the news shocked the scientific community. At the same time, a number of articles on the replication crisis were published, highlighting the flexibility in data analysis and how easy it is to twist conclusions to support a narrative. This motivated Michèle to look further into this phenomenon: “If this is so easy, and things can go wrong at such a scale, how can we still trust anything that's out there?”

Understanding inconsistencies

Statcheck was a tool originally developed for a project that Michèle and other members of her group were working on during her PhD. They had been looking at the prevalence of gross inconsistencies – inconsistencies that potentially change the statistical conclusion – in the literature, to get a sense of the extent of the problem. Because identifying these inconsistencies manually is a lot of work and, ironically, extremely error-prone, they created Statcheck to automate the process. Statistical reporting in psychology typically adheres to the strict APA reporting standard, which must include three values: the test statistic, degrees of freedom and p-value. With any two of these values, the third can be calculated. Statcheck simply scrapes the relevant text reporting the statistics in a paper, recalculates the p-value based on the other two and checks the recalculation against the reported p-value. If there is an inconsistency between the two and this changes the statistical conclusion (for example, the reported p-value is <0.05 whereas the recalculated p-value is >0.05, indicating statistical insignificance), it is detected as a gross inconsistency.

Source: Michèle Nuijten

Michèle and her collaborators applied Statcheck to over 30,000 published articles in psychology to estimate the prevalence of statistical reporting inconsistencies and gross inconsistencies in psychology. To their surprise, almost half of the articles with statistical results hinted at least one p-value inconsistency, and one in eight articles contained at least one gross inconsistency.

Why are these errors so common? In many cases, it is likely that they are simple typing or copy-and-pasting errors when writing: a typo in either one of the three values would raise a red flag. Statistical inconsistencies are not easily detected by means other than recalculation: even for very experienced scientists and reviewers, it is not easy to spot contradictions between the three values by intuition and observation. “A lot of times, my intuitions are also not good enough to read a paper, and see whether their reported values of, for example, t-value=1.32, 26 degrees of freedom, and p-value=0.22, make sense. I would have to recalculate that.”

If gross inconsistencies are caused entirely by innocent typing errors, then there should be equal proportions of reported false positives and negatives. However, Michèle found a small systematic bias towards reporting significant results. There are several explanations for this: it could be that researchers are deliberately rounding down their results to make them look better. Another explanation is that errors in both directions were submitted to journals, but those journals only wanted to publish the ones that reported significant results. A third possibility concerns the rigour with which researchers check their own results. “If researchers are reporting a non-significant result for an experiment that they thought would produce something significant, they might be more likely to go back and check whether they’ve made a mistake. Whereas if it were the other way round, it’s less likely that researchers would go back to check for errors.”

Nevertheless, the vast number of statistical reporting inconsistencies does ring an alarm that should not be ignored. Data analysis, summarisation and reporting are long and complicated processes: unintentional mistakes can easily be made at any stage, and they or their effects can be very difficult to detect. If this number of errors in papers can be found without having access to the raw data or methods, the likely prevalence of mistakes (intentional or not) in the actual data analysis behind the scenes is unfathomable.

What we can change is to come up with ways to avoid these pitfalls and to check ourselves, or to make sure that at least if you make mistakes, you can uncover and correct them.

A spell-checker for statistical reporting

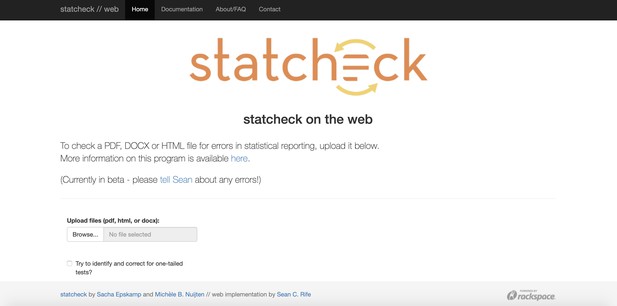

This was when Michèle realised that Statcheck could be part of the solution. “We realised that these are mistakes that are very easy to make, and that maybe we should make Statcheck as easy to use as possible, to make sure that researchers can filter out these errors before they submit to journals.” Statcheck was originally developed as an R-package, but now there is also a very straightforward web version that allows users to upload a paper and quickly check for errors in statistical reporting, which has led to a significant increase in Statcheck’s usage. Michèle is also encouraging journals to adopt Statcheck.

Statcheck.io allows users to upload their manuscript to quickly check for inconsistencies in statistical reporting.

One way to encourage the use of Statcheck and more attention to be paid in general to the accuracy of statistical reporting is to require Statcheck reports at journal submissions. But Michèle sees potential pitfalls in this approach, “because it might give some sort of a false sense of security. The fact that your results are internally consistent doesn't necessarily say anything about the quality of your statistics, it says something about the quality of your reporting, so [...] it's not a bad sign if your paper checks out, but it's also not a guarantee that the statistics are sound, and I fear that people might interpret it that way.” In the same way that the number of typos and grammatical errors in an article doesn’t necessarily reflect the quality of its content or message, editors and reviewers should not reject papers solely based on Statcheck report results.

The research community’s reactions towards a wider adoption of Statcheck were also mixed. In 2016, Michèle’s colleague Chris Hartgerink analysed over 50,000 published articles with Statcheck and published the results as reports on PubPeer, a platform for post-publication peer review. Upon receiving the PubPeer notification regarding the published analysis report, some authors welcomed the analysis and shared the results on social media, and some filed corrections to journals. Some researchers were less impressed: some criticised the way that Statcheck had flagged publications with no inconsistencies, while others feel that the extra analysis and the publication of the results were unsolicited. “I do understand where this sentiment comes from, but also think it’s very interesting to have to ask for permission before posting a critique on a published paper,” Michèle commented. “How can we self-correct and improve if we don’t allow others to review our work?”

At the moment, Michèle finds it more fruitful to promote the use of Statcheck as a “preventive” measure, as an easy-to-use tool to help researchers improve their publications. “Their inconsistent p-values are definitely not the largest problem we are dealing with right now in psychology,” she reflected, “but they are a problem that is very easy to solve. I feel that it’s unnecessary to have these inconsistencies in papers, and if it’s only one thing that we can circumvent, why not?”

[...] just be honest about what you did, try and be as transparent as you can within the environment that you have, and your work will speak for itself.

To err is human

Michèle is familiar with the anxieties of sharing her work online. Prior to releasing Statcheck, her team worked hard on testing to ensure that Statcheck reports are accurate. While she is confident in Statcheck’s performance, having learnt to programme on the go, she was not very confident with the cleanliness or efficiency of the code behind the tool, nor was she well-versed with Git. Nonetheless, she knew that she had to make the tool open-source: “If more people can access my code, they can help improve Statcheck’s performance and help maintain it.” Statcheck has been online for seven years now, and with more users and a slowly growing developers’ community, more features are being added to the tool and existing functionalities are being improved. “We need to acknowledge that we cannot do everything and we are fallible – that is something we cannot change. What we can change is to come up with ways to avoid these pitfalls and to check ourselves, or to make sure that at least if you make mistakes, you can uncover and correct them.” One of the latest tasks is to create a set of unit tests for Statcheck. Michèle had been hesitant to incorporate changes as she feared that they might break the tool; unit tests will ensure that Statcheck will still work as she continues to update it.

As she learns to manage feature requests and feedback to improve Statcheck, Michèle feels that, in many ways, the philosophies of open-source software development and open science are similar. “In the end, science should be about the product that you’re delivering, and about inching closer to the truth,” she says, “and I think the only way to do that with good quality is to get together and help each other.” She thoroughly enjoys talking about Statcheck and is grateful for the suggestions and comments she has received.

I think we’re in the middle of a change in culture, so if you’re starting as a new scientist, there’s so much you can contribute.

Reflecting on her journey from a researcher in psychology to an open-source tool creator, community maintainer and open-science advocate, Michèle feels that it is an extremely exciting time to be in science. “It’s easy to become cynical and pessimistic about the state of scientific research, with all the worries about the lack of replicability, irreproducible articles and all the mistakes that we are uncovering,” she says, “but I think we’re in the middle of a change in culture, so if you’re starting as a new scientist, there’s so much you can contribute.”

Much like the development of Statcheck, a researcher’s journey to making their research more open should not be an all-or-nothing attempt at perfection, but rather a continuous process of learning from errors and from others. Michèle encourages scientists who are new to open science and its practices to just find a method or technique that fits best with their goals, and that they can understand and are comfortable with, and start from there. “In the end, it all revolves around transparency – just be honest about what you did, try and be as transparent as you can within the environment that you have, and your work will speak for itself.”

#

We welcome comments, questions and feedback. Please annotate publicly on the article or contact us at innovation [at] elifesciences [dot] org.

If you would like to learn more about p-values and significance testing, please join our upcoming webinar on October 9, 2019 at 4–5.30BST.

Do you have an idea or innovation to share? Send a short outline for a Labs blogpost to innovation [at] elifesciences [dot] org.

For the latest in innovation, eLife Labs and new open-source tools, sign up for our technology and innovation newsletter. You can also follow @eLifeInnovation on Twitter.