Response to comment on "Magnetosensitive neurons mediate geomagnetic orientation in Caenorhabditis elegans"

Figures

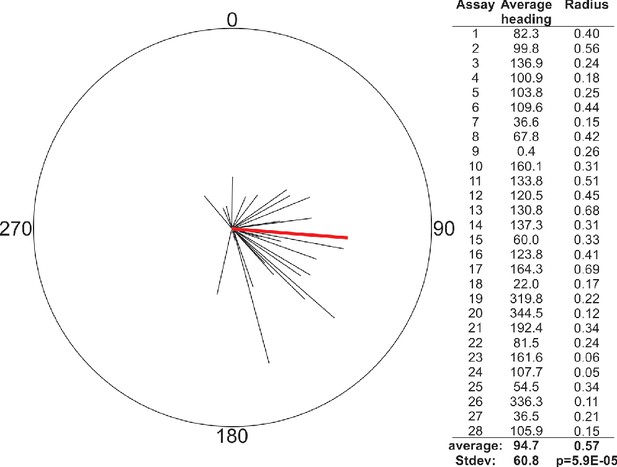

Reanalysis of population data from horizontal field assay in Vidal-Gadea et al., 2015 confirms strong orientation with respect to imposed magnetic field.

Well-fed N2 worms were placed in the center of a 10 cm diameter plate and allowed to migrate freely for 30 min as an earth-strength magnetic field was imposed across the surface of the plate. Worms were trapped by sodium azide at the perimeter. The vector averages for each of the 28 assays (black lines) are plotted as well as the average of these vectors (red line). Vector average values are listed on right. This analysis found a significantly biased vector average of 94.7° (p<0.0001) that was not statistically different from our previously reported value of 132° based on the analysis of individual worms.

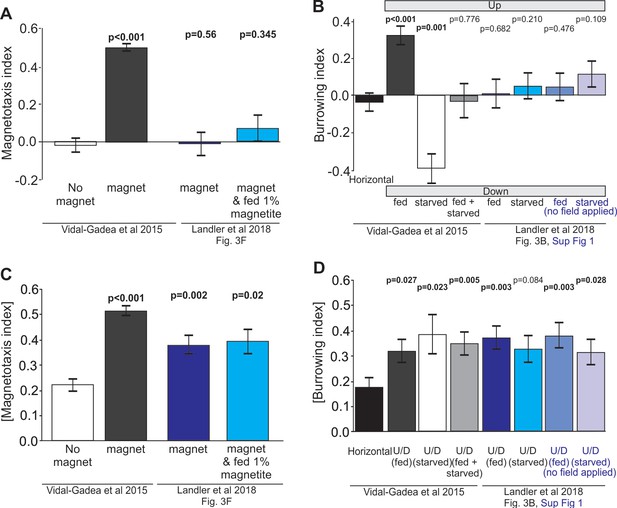

Reanalysis of data suggests that positive results may have been masked in Landler et al., 2018 by testing worms in both fed and starved states and omitting controls.

(A) Comparison of magnetotaxis data reported by Vidal-Gadea et al., 2015 and Landler et al., 2018 obtained by measuring their plots. Figure 3B and F, and Figure 3B, Figure 3—figure supplement 1 were reproduced from Landler et al., 2018; published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)). Because Landler et al. omitted no-magnet control data, we used no-magnet control data from Vidal-Gadea et al., 2015. We found that Landler et al., 2018 worms fed OP50 bacteria (or OP50 plus 1% magnetite) show no significant orientation versus no-magnet control worms. (B) Under the hypothesis that Landler et al might have combined fed and starved worms because their assays were run for twice as long, we used the absolute value of the magnetotaxis index to reveal evidence that worms display a biased migration in the presence of a magnetic field (irrespective of the towards or away sign of their migration). We found that both magnet treatments in Landler et al., 2018 resulted in significantly biased migration when compared with no-magnet controls. (C) We also analyzed burrowing data from Landler et al., 2018 and used our horizontal controls because they were omitted in Landler et al., 2018. We demonstrate that combining data from fed and starved worm abolished significant burrowing indexes that were otherwise observed from each of these populations. Similarly, comparison of Landler et al., 2018 burrowing indices to our horizontal controls (N = 24) revealed no burrowing bias in their field up results for either fed or starved conditions. (D) However, when we compared the absolute value of burrowing bias we found that our combined fed + starved group, as well as Landler et al.’s ‘fed’ worms now showed significant bias when compared to horizontal controls. All tests based on Mann-Whitney Ranked Sum Tests.

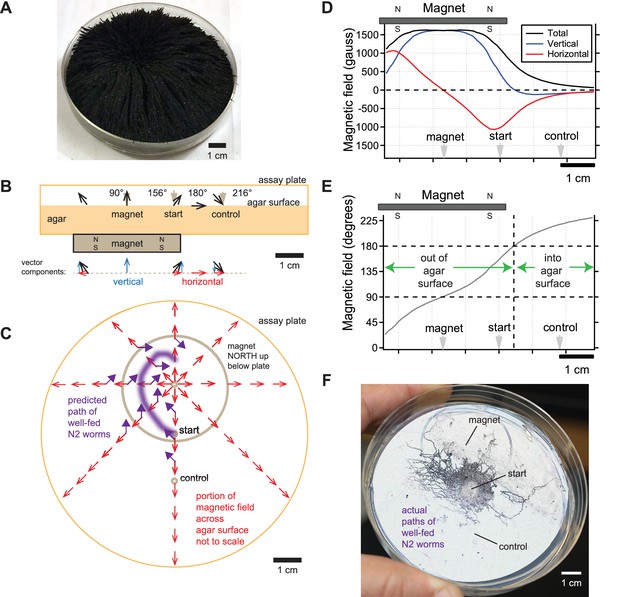

Directional information in magnetic field predicts C. elegans magnetotaxis trajectory.

(A) The direction of iron filings scattered across an assay plate reveals the general shape of magnetic field emanating from a 1.5’ diameter magnet, north-facing up beneath the plate. (B) Side view of magnetic field lines and their vertical and horizontal components across the surface of the agar-filled plate. Magnet and plate shown to scale. Field line strength not to scale. Gray arrowheads denote start location for worms and points where azide was spotted above the magnet and control goals. (C) Top view of horizontal component of magnetic field (red arrows) across the surface of the agar-filled plate. Note that magnetic north points directly away from the center of the magnet everywhere on the plate. Wild-type N2 worms prefer to move at 132° to magnetic north, which predicts the trajectory (purple arrows and line). Field lines not to scale. (D) Strength of the total magnetic field and its vertical and horizontal components across the agar surface. (E) Inclination angle of the magnetic field across the agar surface. (F) Majority of observed trajectories for N2 worms in the magnetotaxis assay arc left of magnet consistent with prediction.

Additional files

-

Supplementary file 1

Combinatorial analysis shows magnetic orientation is distinct from other sensory modalities.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.31414.005

-

Transparent reporting form

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.31414.006