Mummified baboons reveal the far reach of early Egyptian mariners

Figures

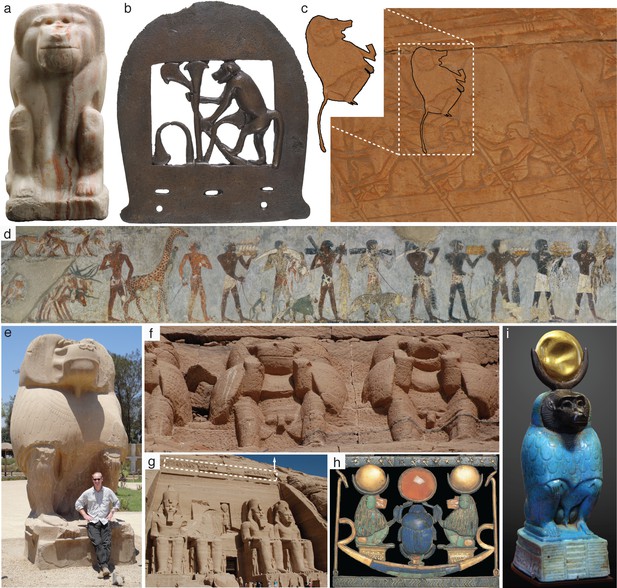

Egyptian iconography of Papio hamadryas, a tradition exceeding 3000 years.

(a) Statuette inscribed with the name of King Narmer, Early Dynastic Period, 1st Dynasty, ca. 3150–3100 BC (no. ÄM 22607, reproduced with permission from the Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung, 2020, under the terms of a CC0 1.0 license. (b) Bronze axe head, Middle Kingdom, 12th or 13th Dynasty, ca. 1981–1640 BC (no. 30.8.111, reproduced with permission from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2020, under the terms of a CC0 1.0 license. (c) Reliefs at the mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut [Deir el-Bahari]. A hamadryas baboon sits in the rigging of a ship. It is one of five being imported from Punt; New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, ca. 1473–1458 BC. (d) Wall painting in the mortuary chapel of Rekhmire (TT 100), Vizier to Tuthmose III and Amenhotep II. A baboon (P. hamadryas) is shown as tribute in a procession from Nubia. Three vervets (Chlorocebus aethiops) are also illustrated, one of which climbs the neck of a beautifully rendered giraffe; New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, ca. 1479–1425 BC. (e) Large 35-ton statue at Hermopolis Magna (author NJD shown for scale); erected by Amenhotep III, New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, ca. 1370 BC. (f) Frieze of baboons on the east-facing facade of the rock-cut temple of Abu Simbel (g), New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, ca. 1265 BC. The raised arms are interpreted as a posture of adoration toward the rising sun, whereas the open mouth may represent vocal behavior (te Velde, 1988). (h) Pectoral necklace of Tutankhamun; baboons are surmounted with lunar disks and simultaneously adoring the central solar disk, a rare combination of two stereotypical postures; New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, ca. 1341–1323 BC (no. JE 61885, Museum of Egyptian Antiquities). (i) Faience figurine and exemplary representation of Thoth: a male P. hamadryas in a seated posture, hands on knees, and surmounted by a lunar disc, Ptolemaic period, 332–30 BC (no. E 17496, Musée du Louvre).

© 2020, Rama, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0. Figure 1I is reproduced with permission from Rama, 2020, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0; this image is not distributed under the terms of the CC0 1.0 license, and further reproduction of this image panel should adhere to the terms of the CC-BY-SA 3.0 license.

© 2019, Sandro Vannini. All rights reserved. Figure 1D is reproduced with permission from Sandro Vannini, 2019; this image is not distributed under the terms of the CC0 1.0 license, and further reproduction of this image panel would need permission from the copyright holder.

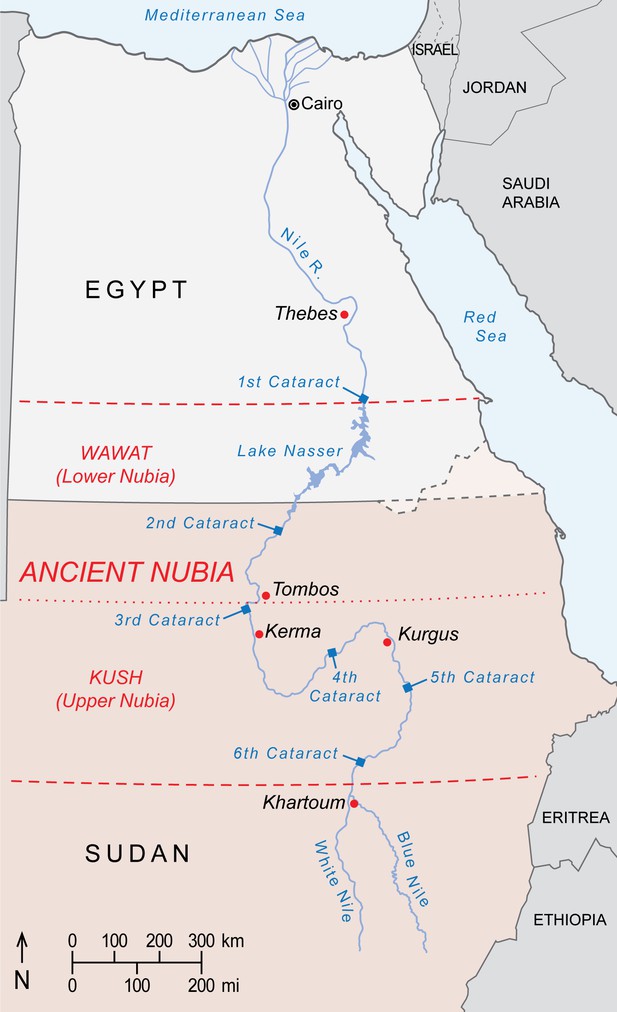

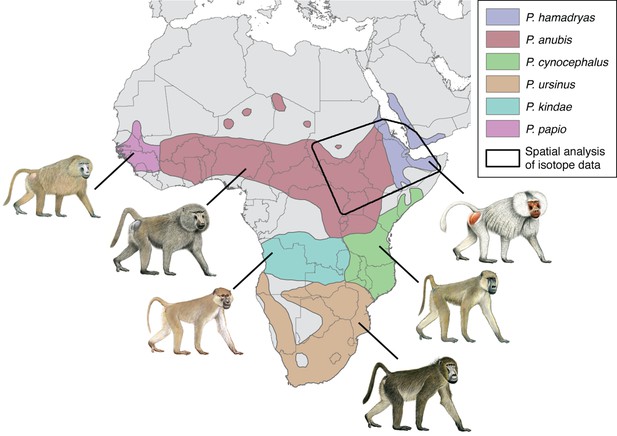

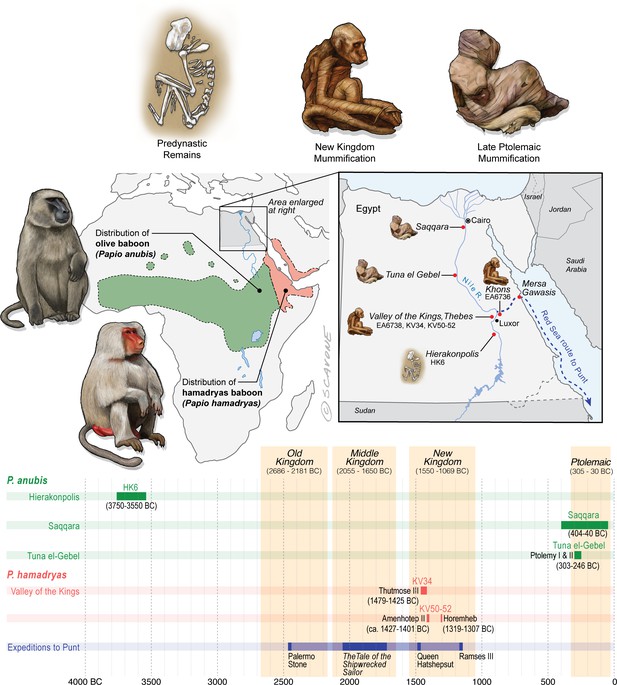

Modern geographic distribution of baboons (Papio) in Africa and southwest Arabia.

The polygon illustrates our area of geospatial analysis, which encompasses regions inhabited by sacred baboons (P. hamadryas) and olive baboons (P. anubis).

Egypt lies well beyond the distributions of P. anubis and P. hamadryas, and there is no evidence of natural populations in Egypt during antiquity.

The remains of baboons in Egypt are therefore interpreted as evidence of foreign trade. This figure puts the present study specimens—EA6736, EA6738, and those of Saqqara—into context by illustrating spatiotemporal variation in the preservation of baboons, emphasizing differences in taxonomy, wrapping, and deposition (i.e., burials, tombs, or catacombs). Horizontal bars represent the temporal spans of baboon-bearing archaeological sites and known expeditions to Punt. Every New Kingdom specimen of P. hamadryas is penecontemporaneous with expeditions to Punt and associated with a royal temple or tomb. The quality of New Kingdom mummification is often extremely high, in part because the limb and tail elements were wrapped individually. Excluded from this figure is a baboon of uncertain taxonomy and disposition found buried in a palace at Tell el-Dab’a, and dating from the 18th Dynasty (von den Driesch, 2006). Mersa Gawasis is a Middle Kingdom harbor and port that was used to launch and receive seafaring voyages to Punt.

Illustration by William Scavone, Kestrel Studios.

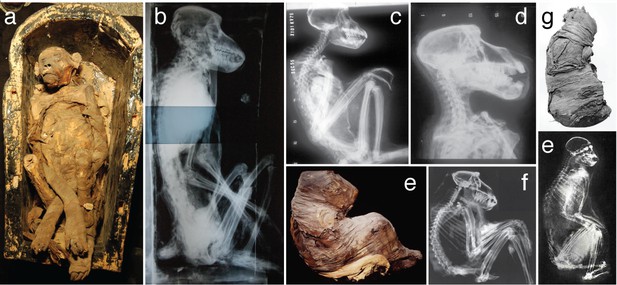

The British Museum holds two mummified baboons with New Kingdom attributions.

(a) EA6736 is attributed to P. hamadryas (Anderson and de Winton, 1902). The present analysis is based on six strands of hair sourced from the upper right arm. (b) EA6736 was the subject of an early radiograph in 1899, which revealed the absence of four canine teeth (Anderson and de Winton, 1902). (c) EA6738 is also attributed to P. hamadryas (Anderson and de Winton, 1902), and it was the source of three tissue types: hair, bone, and enamel. It is also devoid of canines Ossification of the corresponding maxillary (d) and mandibular (e) alveolar sockets is evidence that the animal survived the procedure for many years.

Photographs in panels (d) and (e) by author NJD.

© 2020, The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Figure 3A is reproduced from The Trustees of the British Museum, 2020, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0; this image is not distributed under the terms of the CC0 1.0 license, and further reproduction of this image panel should adhere to the terms of the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license).

© 2020, The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Figure 3C is reproduced from The Trustees of the British Museum, 2020, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0; this image is not distributed under the terms of the CC0 1.0 license, and further reproduction of this image panel should adhere to the terms of the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license).

Adult males of Papio hamadryas have large, formidable canine teeth that can be used to telling effect.

Photograph by author NJD.

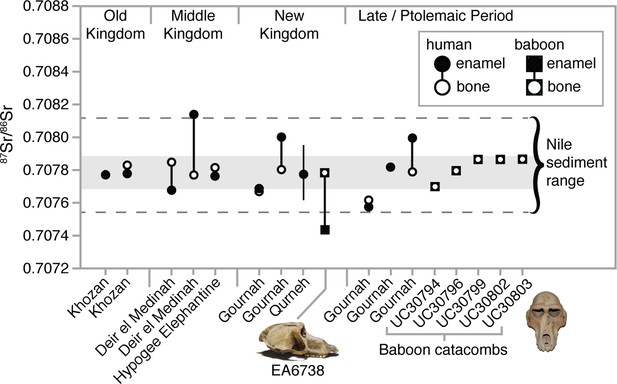

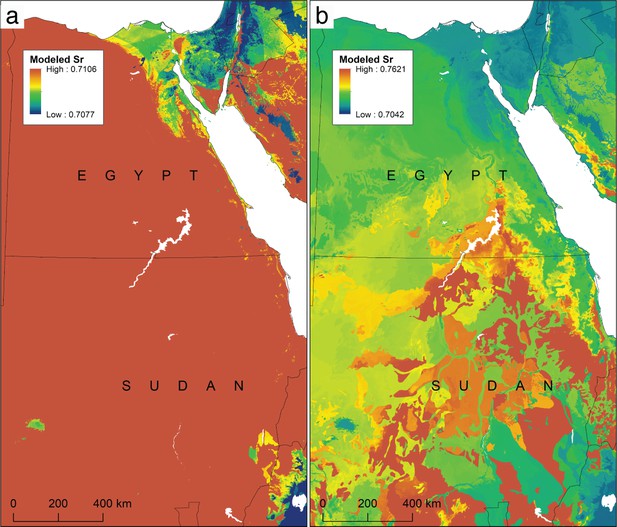

Strontium isotope ratios (87Sr/86Sr) of enamel and bone from humans (Touzeau et al., 2013) and baboons—EA6738 (Papio hamadryas; Thebes) and UC30794-UC30803 (P. anubis; Baboon Catacomb, North Saqqara)—recovered from Egyptian sites.

The data set from Qurneh represents 15 people (mean ± 1 SD; source: Buzon and Simonetti, 2013). The gray-shaded region represents the range of Theban carbonate rocks, whereas the dashed lines define the range of Nile sediments (source: Touzeau et al., 2013). The divergent strontium isotope ratios of EA6738 are telling: the composition of enamel indicates early-life mineralization outside of Egypt, whereas the composition of bone indicates complete diagenesis or many years of living in Egypt prior to death and mummification.

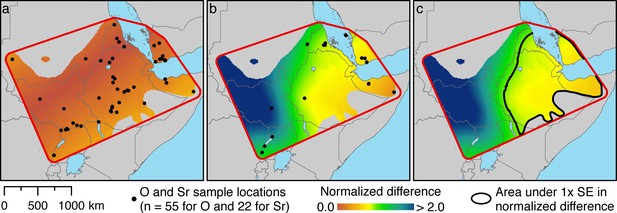

Spatial estimation of isotope ratios and their differences from target values using Empirical Bayesian Kriging.

(a) Specimen locations of modern baboons (black points; source: Appendix 1—table 1) and the normalized difference values for δ18O against our target tissue, the hair of EA6736. (b) Specimen locations of modern baboons (black points; source: Appendix 1—table 2) and the normalized difference values for 87Sr/86Sr ratios against our target tissue, the enamel of EA6738. (c) The combined normalized difference of both isotope ratios against both target tissues. The black line bounds the area within 1 SE. Some points in panels (a) and (b) include multiple samples.

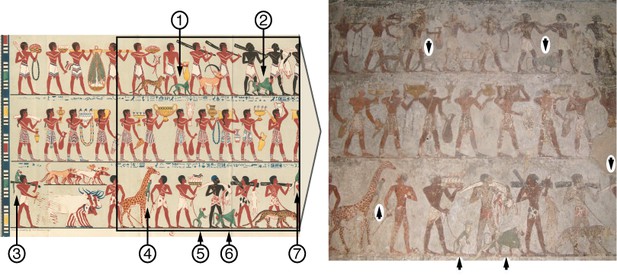

Monkeys were depicted as foreign tribute in the mortuary chapel of Rekhmire (TT 100), Vizier to Tuthmose III and Amenhotep II; New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, ca. 1479–1425 BC.

(Left) Facsimile painting by Hoskins, 1835 (reproduced with permission from the Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library; this image is free to use without restriction). The upper, middle, and lower registers depict processions from Punt, Keftiu (Crete), and Nubia, Lower Nubia, and Khenethennefer, respectively (Güell i Rous, 2018). The tribute bearers from Punt and Nubia are associated with a wide range of natural resources, including seven monkeys, which Hoskins rendered as Papio hamadryas. (Right) Six of seven monkeys are detailed in a photograph by author NJD. Monkeys 2 and 6 are unambiguously P. hamadryas, whereas monkeys 1, 4, and 5 closely resemble vervets (Chlorocebus aethiops) on the basis of tail and cranial morphology.

Radiographs reveal the absence of canine teeth in four mummified baboons.

(a) Specimen of P. hamadryas recovered from KV52, Valley of the Kings, in 1906 (accession no. MM39, Mummification Museum, Luxor). The absence of canines is evident in the corresponding radiograph of MM39 (b) as well as those of two males, (c) JE38746 and (d) JE38744, recovered from KV51 in 1906 and accessioned in the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, Cairo. In general, the extraction of canine teeth is a hallmark of the New Kingdom; however, it is evident in at least one specimen (e and f) from the Ptolemaic period, demonstrating that the practice is imperfect evidence of a New Kingdom provenance. This specimen has no feet for unknown reasons (accession no. AMM 15). A mummified monkey (g) found with Maetkare (1070–945 BC), a high priestess of the 21 st Dynasty, is often described as a young specimen of P. hamadryas based on the radiograph (e) of Harris and Weeks, 1973; however, the animal is equipped with adult dentition and is therefore a smaller species, probably Chlorocebus aethiops or Erythrocebus patas (Ikram and Iskander, 2002). It is also missing its canine teeth (accession no. JE26200(e), Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, Cairo).

© 2008, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden. Images in panels e and f reproduced from the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, 2008, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0; these images are not distributed under the terms of the CC0 1.0 license, and further reproduction should adhere to the terms of the CC-BY-SA 3.0 license.

Sources of Late/Ptolemaic period specimens of Papio anubis.

(a) Entrance to the Baboon Catacomb, North Saqqara, discovered in 1968 (Emery, 1969). (b) Niches cut into the walls of the upper gallery. (c) Each niche accommodated a single linen-wrapped baboon in a custom-built rectangular wooden box, infilled with gypsum plaster (Emery, 1970). The capacity of the catacomb was 437 burials (Goudsmit and Brandon-Jones, 1999). (d) Jettisoned osteological remains are present in some niches, possibly the result of Roman-era destruction. Emery, 1969 described the wreckage as a 'frenzy of religious intolerance’. (e) Inventory organized by the 1996 joint expedition mounted by the Egypt Exploration Society and the University of Amsterdam. See Davies, 2006 for detailed object descriptions. In some cases, the skeletal remains of baboons escaped destruction, existing intact and held together by thick layers of bandages. (f) Skulls from the Baboon Catacomb were donated to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, University College London, in 1969. Detached bone fragments are often present in the specimen boxes, and five such samples were analyzed here. (g) Chamber in the subterranean galleries of Tuna el-Gebel; the baboonification of Thoth is evident in the granite statue at the far end. (h) In the early Ptolemaic period, each niche was fronted by a staircase made of stone slabs, flanked by a pair of conical stone columns that acted as bases for flat bronze offering plates. Between them was a limestone offering-table for libations (Kessler and Nur el-Din, 2005).

Photographs by author NJD.

Recent publication of a global bioavailable strontium isoscape motivated us to consider whether the enamel of EA6748 could have an 87Sr/86Sr ratio (0.707431) that corresponds to areas now devoid of baboons, such as Nubia in northern Sudan and southern Egypt.

(a) Spatial model of the Sr isoscape based on the data set of Bataille et al., 2020, with values mapped using the same color gradient and range of Sr values in our own spatial model (Appendix 1—figure 7). (b) Same, but with a range based on the global mean ±2 SD in the data set of Bataille et al., 2020.

Enamel fragments associated with EA6738.

The detached fragments were found in the specimen box and re-fit to the source tooth to verify association.

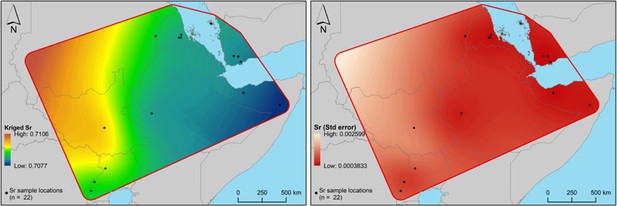

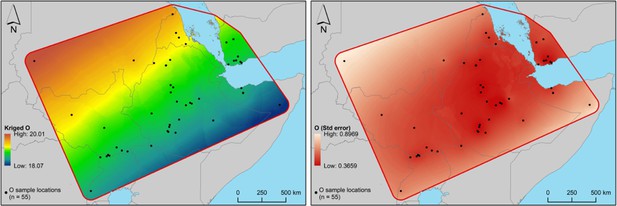

Spatial estimation of δ18O values (left) and the spatially distributed estimated error of prediction (right) from Empirical Bayesian Kriging.

Black points indicate specimen locations of modern baboons (n = 55; some points include multiple samples).

Tables

Sources and identifications of baboon hair samples, together with corresponding oxygen isotope values (δ18O; ‰, VSMOW) and geoprovenance, as described by collectors, and converted to present-day country names and geographic coordinates in decimal degrees (°, + = N, - = S for Latitude; + = E for Longitude).

| Source | Accession/ID | δ18O | Source description 1 | Source description 2 | Country | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NJD | QENJD7 | 19.8 | Queen Elizabeth National Park | Uganda | −0.010358 | 30.0028 | |

| AMNH | 184247 | 18.6 | W Nile Dist. | Koboko Co., Utukiliri | Uganda | 3.4 | 30.95 |

| BMNH | 1931.4.1.1 | 19.9 | West Madi, N.P. | Pulu | Uganda | 3.5 | 31.5833 |

| BMNH | 1937.7.24.1 | 20.1 | Laropi, Moyo | West Madi | Uganda | 3.56667 | 31.85 |

| AMNH | 184248 | 15.2 | W Nile Dist. | W. Madi, Moyo | Uganda | 3.64967 | 31.7239 |

| PCM | Uganda | 17.4 | Kedef Valley | W. of Dodinga | Sudan | 4 | 33.6667 |

| FMNH | 67015 | 16.7 | E Equatoria | Torit 50 mi SE; Ikoto | Sudan | 4.1 | 33.1 |

| FMNH | 67016 | 19.2 | E Equatoria | Torit 50 mi SE; Ikoto | Sudan | 4.1 | 33.1 |

| NMNH | 299672 | 17.6 | Al-Istiwa’Iyah Ash-Sharqiyah | Torit | Sudan | 4.40806 | 32.575 |

| BMNH | 1900.11.7.1 | 19.0 | R. Omo, L. Rudolf | Ethiopia | 4.58333 | 36.05 | |

| FMNH | 32906 | 18.0 | Sidamo | Boran Gatelo | Ethiopia | 5.91667 | 38.4667 |

| BMNH | 1967.1152 | 19.1 | R. Cullufu | between L. Abaya and L. Chamo | Ethiopia | 6 | 37.75 |

| BMNH | 1967.1151 | 19.8 | southwest corner L. Abaya | near Arba Minch | Ethiopia | 6.08333 | 37.6667 |

| AMNH | 82184 | 16.4 | Bor to Shambe | Sudan | 6.36667 | 31.3333 | |

| BMNH | 1964.2174 | 18.6 | Near NW Lake Abaya | Gamo-Gofa | Ethiopia | 6.5 | 37.8333 |

| FMNH | 27034 | 18.9 | Arusi | Abul Casim (”Abu el Kassim’) | Ethiopia | 6.7 | 37.8833 |

| FMNH | 27036 | 19.5 | Bale | Webi Shebeli | Ethiopia | 7.16667 | 42.2333 |

| FMNH | 27043 | 17.2 | Shoa, Salali | Awada R; E side; nr Mt Duro | Ethiopia | 7.23278 | 38.8147 |

| BMNH | 1902.9.2.1 | 21.2 | Waw [Wau], R. Tur [Jur] | Bahr el Ghazal | Sudan | 7.66667 | 28.0667 |

| AMNH | 81061 | 16.7 | Sidamo | Agarasalam | Ethiopia | 7.83333 | 36.0667 |

| AMNH | 81062 | 17.4 | Sidamo | Agarasalam | Ethiopia | 7.83333 | 36.0667 |

| PCM | ABYS II 60 | 21.3 | Hawash | 6 hr from Oulanketi | Ethiopia | 8.67513 | 39.4938 |

| CJJ | 20.0 | average of 20 P. anubis (Moritz et al., 2012) | along Awash River, near falls | Ethiopia | 8.85 | 40.0667 | |

| CJJ | 19.9 | average of 23 P. hamadryas (Moritz et al., 2012) | north of Lake Basaka | Ethiopia | 8.91667 | 39.9 | |

| FMNH | 8171 | 15.5 | Arusi | Menegesha | Ethiopia | 9.03333 | 38.5833 |

| FMNH | 27188 | 13.3 | Shoa, Salali | Mugher R; N bank Mulu 25 mi NW | Ethiopia | 9.33333 | 40.8 |

| MZUF | 6278 | 19.7 | Garoe | Run | Somalia | 8.8 | 48.8667 |

| BMNH | 1910.10.3.1 | 23.2 | Upper Sheikh | British Somaliland | Somalia | 9.93333 | 45.2 |

| BMNH | 1902.9.9.3 | 19.1 | Ahuillet, Kotai | West Shoa | Ethiopia | 9.95 | 37.9667 |

| FMNH | 1474 | 19.4 | Togdheer | Qar Goliis (”Golis’) Mts, Shiikh Pass | Somalia | 9.96667 | 45.2 |

| CMZ | E.7543B | 17.8 | Somaliland | Berbera | Somalia | 10.4333 | 45.0167 |

| FMNH | 27035 | 18.7 | Gojjam | Bichena | Ethiopia | 10.45 | 38.2 |

| FMNH | 27041 | 17.1 | Gojjam | Jigga 5 mi E | Ethiopia | 10.6667 | 37.95 |

| FMNH | 27042 | 18.6 | Gojjam | Jigga 5 mi E | Ethiopia | 10.6667 | 37.95 |

| FMNH | 27037 | 18.8 | Gojjam | Jigga 5 mi E | Ethiopia | 10.6667 | 37.95 |

| FMNH | 27192 | 17.6 | Begemdir | Gondar | Ethiopia | 12.6 | 37.4667 |

| FMNH | 27191 | 19.0 | Begemdir | Gondar 15 mi NE | Ethiopia | 12.6167 | 37.4833 |

| BMNH | 1855.12.24.19 | 13.0 | Subaihi country | 60 miles NW of Aden | Yemen | 12.75 | 43.7 |

| FMNH | 27193 | 19.3 | Begemdir | Metemma 15 mi SE Gendoa R Camp | Ethiopia | 12.8333 | 36.2833 |

| BMNH | 1973.1811 | 15.6 | ?Aden | South Yemen | Yemen | 12.9196 | 45.0203 |

| BMNH | 1920.7.30.1 | 20.2 | Jebel Marra | Darfur | Sudan | 13 | 24.3333 |

| BMNH | 1904.8.2.1 | 20.9 | Mountainous country | behind Lahej, Aden | Yemen | 13.0167 | 44.9 |

| BMNH | 1914.3.8.1 | 22.7 | Kamisa, R. Dinder | Sudan | 13.0833 | 34.25 | |

| BMNH | 1914.3.8.2 | 22.8 | Kamisa, R. Dinder | Sudan | 13.0833 | 34.25 | |

| DEW | 104 | 20.5 | Jebel Iraf | Yemen | 13.1167 | 44.25 | |

| FMNH | 27183 | 18.7 | Begemdir | Devark 30 mi NE Gonder | Ethiopia | 13.153 | 37.883 |

| DEW | 55 | 15.3 | Salah-Taiz | Yemen | 13.15 | 44.4667 | |

| BMNH | 1902.11.22.1 | 21.2 | Azraki Ravine | Yemen | 13.5333 | 44.65 | |

| BMNH | 1939.1027 | 21.9 | Senafe | Habesch | Eritrea | 14.7167 | 39.4333 |

| DEW | 30 | 17.3 | Jebel Bura’a | Yemen | 14.9 | 43.4833 | |

| DEW | 152 | 14.9 | Sana’a | Yemen | 15.2167 | 44.1833 | |

| DEW | 106 | 15.5 | Bab Al Yemen | Yemen | 15.2167 | 44.1833 | |

| PCM | ABYS I | 18.1 | Nr. Asmara | Eritrea | 15.3333 | 38.75 | |

| MZUF | 100 | 19.7 | Ausebo | presso Keren, (Bogos?) | Eritrea | 15.7833 | 38.45 |

| PCM | Sudan | 21.0 | Jebel | Kassala | Sudan | 17.5833 | 38.1 |

-

Source abbreviations: American American Museum of Natural History (AMNH); Clifford J. Jolly (CJJ); Derek E. Wildman (DEW); Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH); Museo di Storia Naturale di Firenze, La Specola, University of Florence (MZUF); Nathaniel J. Dominy (NJD); National Museum of Natural History (NMNH); Natural History Museum, formerly the British Museum of Natural History (BMNH); Powell-Cotton Museum (PCM); and University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge (CMZ).

Sources and identifications of baboon enamel and bone samples, together with corresponding strontium isotope compositions (87Sr/86Sr) and geoprovenance, as described by collectors, and converted to present-day country names and geographic coordinates in decimal degrees (°, + = N, - = S for Latitude; + = E for Longitude).

| Source | Accession/ID | (87Sr/86Sr) | Source description 1 | Source description 2 | Country | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MZUF | 6278 | 0.707604 | Garoe | Run | Somalia | 8.80 | 48.8667 |

| BMNH | 1927.8.14.1 | 0.709239 | Lower Sheikh | British Somaliland | Somalia | 9.98333 | 45.2167 |

| BMNH | 1910.10.3.1 | 0.707509 | Upper Sheikh | British Somaliland | Somalia | 9.93333 | 45.20 |

| AMNH | 82185 | 0.712311 | Bor to Shambe | Sudan | 6.36667 | 31.3333 | |

| PCM | Sudan II | 0.708761 | Eireirib | Red Sea Province, Kassala | Sudan | 15.45 | 36.40 |

| NJD | MFNP6 | 0.711806 | Murchison Falls National Park | Uganda | 2.27729 | 31.4617 | |

| NJD | MFNP8 | 0.711651 | Murchison Falls National Park | Uganda | 2.27729 | 31.4617 | |

| NJD | MFNP3 | 0.711659 | Murchison Falls National Park | Uganda | 2.27729 | 31.4617 | |

| NJD | SEM BAB3 | 0.709508 | Semliki National Park | Uganda | 0.908781 | 30.356 | |

| NJD | SEM BAB2 | 0.708062 | Semliki National Park | Uganda | 0.908781 | 30.356 | |

| NJD | QENP5 | 0.707549 | Queen Elizabeth National Park | Uganda | −0.01036 | 30.0028 | |

| AMNH | 81062 | 0.707375 | Sidamo | Agarasalam | Ethiopia | 7.83333 | 36.0667 |

| AMNH | 81061 | 0.707406 | Sidamo | Agarasalam | Ethiopia | 7.83333 | 36.0667 |

| PCM | ABYS I | 0.707030 | near Asmara | Eritrea | 15.3333 | 38.75 | |

| NJD | Eritrea 1 | 0.707788 | near FilFil | Eritrea | 15.6167 | 38.9667 | |

| NJD | Eritrea 2 | 0.707925 | near FilFil | Eritrea | 15.6167 | 38.9667 | |

| NJD | Eritrea 3 | 0.709306 | Asmara | Eritrea | 15.3324 | 38.9262 | |

| DEW | T650 A | 0.707922 | Jebel Sabir | Yemen | 13.5833 | 44.20 | |

| DEW | T650 B | 0.707937 | Jebel Sabir | Yemen | 13.5833 | 44.20 | |

| MZUF | 11329 | 0.708758 | Isole Farasan | Isola Kebir | Saudi Arabia | 16.7065 | 41.9076 |

| BMNH | 1902.11.22.1 | 0.708158 | Azraki Ravine | Saudi Arabia | 13.5333 | 44.65 | |

| BMNH | 1904.8.2.1 | 0.708629 | mountainous country | behind Lahej, Aden | Yemen | 13.0167 | 44.90 |

| MZUF | 1669 | 0.707928 | Balad (dintorni) | Somalia | 2.36 | 45.39 | |

| MZUF | 3267 | 0.707693 | Giohar, ex Villabruzzi | Somalia | 2.78 | 45.50 | |

| MZUF | 3016 | 0.707935 | Gelib | Isola Alessandra | Somalia | 0.49 | 42.78 |

| MZUF | 2557 | 0.707665 | Afgoi | Somalia | 2.14 | 45.12 | |

| MZUF | 2460 | 0.708416 | Jesomma | Bulo Burti | Somalia | 3.85 | 45.57 |

| AMNH | 216246 | 0.723349 | Manica and Sofala | Mozambique | −19.20 | 34.85 | |

| AMNH | 216250 | 0.720642 | Inhambane | Zinave | Mozambique | −21.67 | 33.53 |

| AMNH | 216247 | 0.724701 | Manica and Sofala | Mozambique | −19.20 | 34.85 | |

| AMNH | 216249 | 0.722069 | Inhambane | Zinave | Mozambique | −21.67 | 33.53 |

-

Source abbreviations: American American Museum of Natural History (AMNH); Derek E. Wildman (DEW); Museo di Storia Naturale di Firenze, La Specola, University of Florence (MZUF); Nathaniel J. Dominy (NJD); Natural History Museum, formerly the British Museum of Natural History (BMNH); and Powell-Cotton Museum (PCM). Nota bene: samples from beyond the distributions of Papio anubis and P. hamadryas were excluded from further analysis.

Strontium isotope compositions (87Sr/86Sr) of detached bone fragments from skulls recovered from the Baboon Catacomb, North Saqqara, and accessioned in the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, University College London.

| Accession number | Species | 87Sr/86Sr | ±2 s | Notes: Groves, 1970 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UC30794 | Papio anubis | 0.707775 | 0.000006 | Adult female |

| UC30796 | Papio anubis | 0.707845 | 0.000006 | Adult female |

| UC30799 | Papio anubis | 0.707848 | 0.000006 | Juvenile II male |

| UC30802 | Papio anubis | 0.707848 | 0.000006 | Juvenile I, probably female |

| UC30803 | Papio anubis | 0.707678 | 0.000006 | Juvenile I, sex indeterminate |

| UC30804 | Macaca sylvanus | 0.707851 | 0.000007 | Adult male |

| UC30807 | Chlorocebus aethiops | 0.708209 | 0.000008 | Adult male |