Point of View: Why both sides of the gender equation matter

Figures

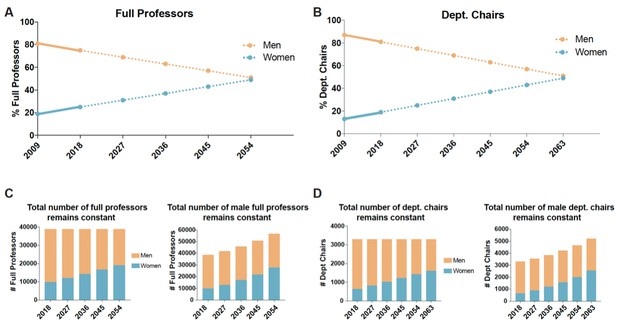

What is needed to achieve gender parity at the full professor and department chair levels in US medical schools?

(A) The graph shows the percentage of male full professors (orange circles) and female full professors (blue circles) by year. Data from 2009 to 2018 were collected by the AAMC (solid lines), while data from 2018 to 2054 are linear projections (dotted lines) based on the 2009–2018 trends. From these projections, gender parity (within one percentage point) would be achieved in 2054. (B) The graph shows the percentage of male department chairs (orange circles) and female department chairs (blue circles) by year. Data from 2009 to 2018 were collected by the AAMC (solid lines), while data from 2018 to 2063 are linear projections (dotted lines) based on the 2009–2018 trends. From these projections, gender parity (within one percentage point) would be achieved in 2063. (C) Projections in absolute numbers assuming the total number of full professors remains constant (left), or the total number of male full professors remains constant (right). To maintain 38,767 full professor positions (the number in 2018, including 23 with gender unreported), the number of women would need to increase by approximately 9,590 (from 9,794–19,384) and the number of men would need to decrease by approximately 9,566 (from 28,950–19,384). Alternatively, if the number of male full professors remains constant, an additional 19,156 full professor positions would be needed to achieve parity. (D) Projections in absolute numbers assuming the total number of department chairs remains constant (left), or the total number of male department chairs remains constant (right). To maintain 3,292 department chair positions (the number in 2018), the number of women would need to increase by 1,007 (from 639 to 1,646) and the number of men would need to decrease by 1,007 (from 2,653–1,646). Alternatively, if the number of male department chairs remains constant, an additional 2,014 department chair positions would be needed to achieve parity. In all panels, data for men is shown in orange and data for women in shown in blue. Data from AAMC, 2020.

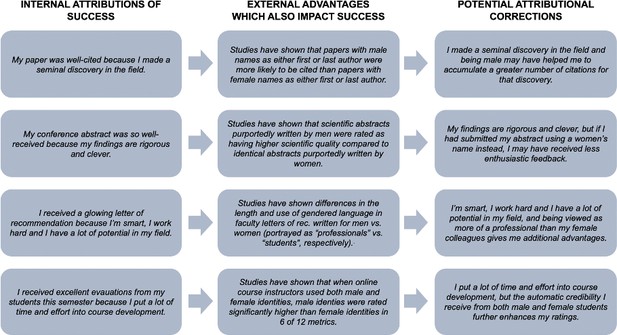

Examples of the self-serving bias and its relevance for gender equality in STEMM fields.

Focusing on the self-serving bias, four theoretical internal attributions of success are shown on the left; the corresponding documented external factors, which also impact success, are shown in the middle; and potential attributional corrections are shown on the right. Here, examples were selected from studies of gender bias in paper citations (Larivière et al., 2013), assessment of scientific quality in conference abstracts (Knobloch-Westerwick et al., 2013), faculty letters of recommendation (Trix and Psenka, 2003) and teaching evaluations (MacNell et al., 2015).