The Natural History of Model Organisms: The secret lives of Drosophila flies

Abstract

Flies of the genus Drosophila, and particularly those of the species Drosophila melanogaster, are best known as laboratory organisms. As with all model organisms, they were domesticated for empirical studies, but they also continue to exist as wild populations.

Decades of research on these flies in the laboratory have produced astounding and important insights into basic biological processes, but we have only scratched the surface of what they have to offer as research organisms. An outstanding challenge now is to build on this knowledge and explore how natural history has shaped D. melanogaster in order to advance our understanding of biology more generally.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.06793.001Introduction

From its first use in the laboratory in the early 1900s until the present day, Drosophila melanogaster has been central to major breakthroughs in genetics. The use of this fruit fly as a model organism began with the pioneering work of Thomas Hunt Morgan, who was awarded the 1933 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for ‘his discoveries concerning the role played by the chromosome in hereditary’. Morgan's former student, Herman J Muller, subsequently received the prize in 1946 ‘for the discovery of the production of mutations by means of X-ray irradiation’. In 1995, the Drosophila researchers, Edward B Lewis, Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard and Eric F Wieschaus shared the prize ‘for their discoveries concerning the genetic control of early embryonic development’. Most recently, Jules Hoffman shared the 2011 prize for ‘discoveries concerning the activation of innate immunity’ in Drosophila.

How did one species of Drosophila, D. melanogaster, come to be a model system? Harvard entomologist Charles Woodworth was the first to rear D. melanogaster, just after the turn of the 20th century. It is not clear why or how he came to breed them, but their short generation time and ease of rearing were probably very appealing attributes. Woodworth then recommended them to his colleague William Castle, who initially worked on mammals but utilized the flies to study inbreeding. During this same period, another entomologist, Frank Lutz at the American Museum of Natural History, also began studying this fly's basic biology, publishing more than a dozen papers about them (Davenport, 1941; Carlson, 2013). It was from Lutz that Thomas Hunt Morgan introduced them into his laboratory at Columbia University. At the time Morgan began his work, the basic principles of heredity were still under debate. Morgan's discoveries and the fact that he attracted a highly talented group of graduate students no doubt fuelled the use of D. melanogaster as a model system.

But what do we know about the biology of this fly in nature? Here, I review what we know of its origins, its biology in the wild and how this differs from what we see in the laboratory, its natural history, and why its natural history matters for laboratory studies, as well as its advantages as a model organism. I also discuss why, even after so many years of intensive investigation, D. melanogaster and its relatives are in an important position to help us address central questions about biology.

Where did D. melanogaster come from and how do these flies live?

D. melanogaster, described by Meigen in 1830, appears to have originated in sub-Saharan Africa (Lachaise et al., 1988). The first out-of-Africa habitat expansion of D. melanogaster is thought to have occurred between 10,000 and 15,000 years ago, when it moved to Europe and Asia (David and Capy, 1988). North America and Australia were colonized more recently (David and Capy, 1988). Subsequent colonization events, especially as human travel has accelerated, have continued to move populations around the globe. Its current distribution is worldwide, being found on every continent and most islands (Markow and O'Grady, 2005b).

A human commensal associated primarily with rotting fruits, D. melanogaster is also associated with a wide array of decaying vegetables and other plant matter. The fact that this fly is an ecological generalist no doubt contributed to the facility with which it was initially propagated in the laboratory, rapidly becoming a popular model system. Drosophila are found worldwide, and their extensive distribution has allowed studies of adaptations to different latitudes.

D. melanogaster do not live alone. Their decaying host resources are also home to many microbes, as well as to other arthropods, including other Drosophila species, all of which they interact with (see Video 1, 2). Some microbes in the decaying material themselves provide food for D. melanogaster, being selectively consumed by larvae or adults. Other microbes are essential for decomposing fruit and other plant matter into substances, such as volatiles, that attract other adult flies to the food source, or for decomposing organic matter into new material, which in turn is consumed by the flies. Along with Drosophila simulans, Drosophila hydei, Drosophila immigrans, and Drosophila busckii, D. melanogaster forms part of what is known as the ‘cosmopolitan guild’ of Drosophila (Atkinson and Shorrocks, 1977). While found in association with these other species, D. melanogaster colonizes the rotting fruits at a particular time during the decay trajectory. First to arrive is D. simulans, followed by D. melanogaster, and then the other species (Nunney, 1990, 1996): this is consistent with D. melanogaster having a higher ethanol tolerance than its relative D. simulans (McKenzie and Parsons 1972, 1974), which arrives earlier, when fewer volatiles have been produced by fermentation. Other arthropods, especially beetles, are also common in the substrate and are predators of the developing flies.

Three members of the cosmopolitan guild of Drosophila feeding.

D. hydei (the larger, dark flies) and D. melanogaster and D. simulans (the smaller, lighter flies) quietly feeding on the juice of a rotting tomato and on the microbes present on it. D. melanogaster and D. simulans are sibling species and are morphologically indistinguishable in the video. Video credit: Therese Ann Markow.

Three members of the cosmopolitan guild of Drosophila interacting at a food source.

Drosophila: D. hydei (the larger, dark flies) and D. melanogaster and D. simulans (the smaller, lighter flies) interacting at a food source. Although there is little sexual dimorphism between males and females of the D. hydei species, males can be distinguished in the video because they approach other flies to court. In the D. melanogaster and D. simulans species, males are smaller than the females and have darker abdomens. These males can also be seen approaching other flies and attempting to court. Attempted courtships are brief and often end when females extrude their ovipositors. Notice that males will approach flies of different sexes and species, and that flies of D. hydei are much less active than those of D. simulans and D. melanogaster. D. melanogaster and D. simulans are sibling species and are morphologically indistinguishable in this video. Video credit: Therese Ann Markow.

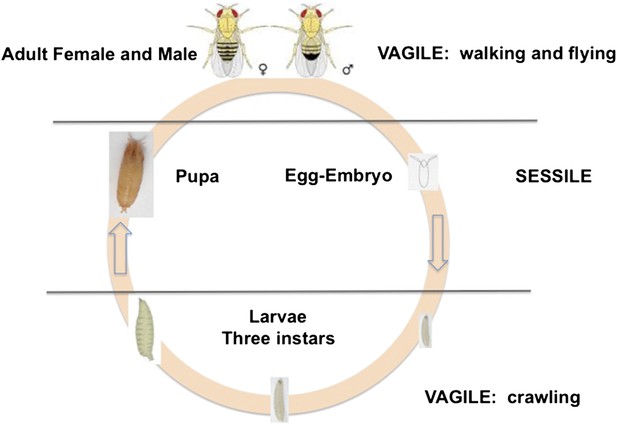

D. melanogaster is holometabolous, meaning it undergoes a metamorphosis from its larval to adult form (Figure 1). Females lay their eggs in necrotic material, and the larvae develop and pupate there. Two life stages are completely immobile: the egg and the pupa. Larvae can move within the resource patch, while adults can fly between patches. Given the sessile status of eggs and larvae, we expect these stages to exhibit adaptations against predation, parasitism and environmental stressors, such as temperature extremes, ultraviolet light and desiccation. Natural selection on behaviors such as oviposition and pupation site selection is therefore expected to be strong.

The life cycle of Drosophila melanogaster.

Egg and pupa stages are sessile, larvae move within the substrate, and adults are highly vagile as their ability to fly enables their dispersal. Different species of Drosophila vary in their larval development times, as well as in the ages at which females and males attain reproductive maturity. Image credit: Therese Ann Markow.

What is different in the lab and field?

In the laboratory, life is simple. Much is constant. Flies are grown in one or more standardized culture media, usually treated with mould inhibitors, such as propionic acid or methylparaben, and antibiotics. While these culture conditions keep flies ‘healthy’ by laboratory standards, they do not represent the conditions that D. melanogaster experience in nature. The fungal, bacterial and viral pathogens (Magwire et al., 2012; Keebaugh and Schlenke, 2014) flies encounter in nature are absent in the laboratory. In the wild, larvae and flies are also exposed to predators, such as ants, beetles, pseudoscorpions and lizards, as well as to parasites, such as wasps and phoretic mites. Encountering food of different types and ages in nature also differs from the benign consistency of the laboratory environment. In the laboratory, flies tend to be reared at a constant temperature and humidity level, while these abiotic variables fluctuate in nature. Laboratory adults also don't need to disperse to find a resource for the next generation.

What is different then, about the flies themselves, when found in nature? Few studies of D. melanogaster have been done in the wild, but those that have reveal a different picture of wild flies. For one thing, they tend to be larger than laboratory reared flies, possibly owing to some, as yet unknown, micronutrients and/or to the fact that in nature, temperatures fluctuate and growth is slower than in culture (Chown and Gaston, 2010). The microbes that associate with D. melanogaster in the laboratory are also far less diverse than those that associate with these flies in the wild (Chandler et al., 2011).

Reproductive behavior and biology, while extensively studied in the laboratory, is less well-understood in the wild. From the few studies conducted in nature, a different picture emerges. For example, in nature, virgins are not separated upon eclosion and stored until used in experimental pairings. Instead, they tend to be mated early and often (Markow et al., 2012). In fact, many D. melanogaster females in the wild appear to have been force-mated by males waiting for them to emerge from their pupa cases (Markow, 2000; Seeley and Dukas, 2011). In addition, while laboratory mated females tend to die earlier than do virgins, the well known ‘cost of mating’ (Fowler and Partridge, 1989), in nature the opposite seems to be true (Markow, 2011). Courtship itself is also different in nature compared to that observed in the laboratory. Laboratory experiments almost universally reveal an advantage to large males when placed with smaller males in ‘choice’ experiments (Alcock, 2013). In nature, however, sexual interactions do not take place in small chambers. Males appear to sort themselves out by size at the mating site, with smaller males often being found in parts of the fruit where there are fewer females and thus fewer matings (Markow, 1988). The mating advantage to larger males is not as apparent in wild populations (Partridge et al., 1987; Markow, 1988). Furthermore, when courted by an undesirable male in nature, where there is ample space to escape, female D. melanogaster rarely decamp, instead, extruding their ovipositor to discourage the suitor (Gromko and Markow, 1993; Video 2).

Untapped potential of Drosophila

Our extensive foundational knowledge of the biology of D. melanogaster places these flies in a very strong position to contribute to our understanding of outstanding issues and questions in biology, supported by the availability of a sequenced genome (Adams et al., 2000) and an array of genomic resources. While a number of future discoveries will concern basic processes in gene action and development, the natural history of D. melanogaster can also inform and guide discoveries relevant to contemporary and pressing problems in human health and environmental change.

Reproduction and biocontrol

The reproductive systems of Drosophila species are among the most variable of any organism (Markow, 1996, 2002; Markow and O'Grady, 2005a). Some of this variability is behavioural. For example, in some species, such as D. hydei and Drosophila nigrospiracula, females will mate multiple times in a single morning, while in others, such as Drosophila subobscura, females will mate once in their lifetime. Some species, such as Drosophila pachea, require weeks for an adult fly to become sexually mature, while in others, such as Drosophila mettleri, either sex can be ready to mate within hours of emerging from the pupa case. The genes that control these behavioural differences can hold clues to controlling the reproduction of economically and medically important insects, such as testse flies and mosquitoes (see Box 1). Morphological variation can also influence the reproductive success of ‘problem’ species. Drosophila suzukii, for example, is an exceptional species that has recently invaded America and Europe from Asia (Rota-Stabelli et al., 2013) and attacks agricultural produce (in particular, by laying its eggs into soft fruits). A sequenced genome (Chiu et al., 2013) and comparative morphological studies of its females' sharp ovipositor (Atallah et al., 2014) provide insights into the basis for its rapid invasion.

Outstanding questions about the natural history of Drosophila

Why can some Drosophila species feed and breed in certain resources while other species cannot?

Why can some Drosophila species tolerate extreme environmental conditions while others cannot?

What accounts for the particular microbial communities found inside the guts of D. melanogaster and of other species?

What accounts for the astounding variability in the reproductive biology of Drosophila species?

An additional aspect of biocontrol is to understand the neurobiological mechanisms by which insects identify their hosts. Here again, discoveries made in D. melanogaster can be applied to economically important species. These discoveries include the first functional mapping of olfactory responses (Hallem and Carlson, 2004), and the use of multiple species' genomes to reveal the ecological and behavioural significance of the evolution of various olfactory receptors (McBride, 2007; Guo and Kim, 2007; Goldman-Huertas et al., 2015). As such, the D. melanogaster toolbox can now be used to disrupt host-seeking behaviors in insects of medical and economic importance (Carey and Carlson, 2011).

Human health

D. melanogaster has played an increasingly important role in the creation of animal models of human disease. Approximately 65% of human disease genes are estimated to have counterparts in D. melanogaster (Chien et al., 2002), most of which are available in the Homophila database (http://superfly.ucsd.edu/homophila/). The number of investigators using D. melanogaster as a model for studying human disease is steadily rising (Pfleger and Reiter, 2008), especially for more complex disorders, such as heart disease (Piazza and Wessells, 2011), mental and neurological illness (Pandey and Nichols, 2011), and obesity (Trinh and Boulianne, 2013).

Complex health problems tend to be rooted in the interaction between multi-factorial genotypes and the environment. What role can natural history play in our ability to understand these interactions with a view towards disease mitigation and treatment? In the past few decades, the importance of the gut microbiome for models of human health has grown. The D. melanogaster microbiome, under laboratory conditions, turns out to be quite simple, with an average of ten culturable bacterial species (Lee and Hase, 2014), and has provided insights into the relationship between gut microbiota and processes such as intestinal function (Lee and Lee, 2014) and insulin signaling (Shin et al. 2011). Of considerable interest is that the microbiome of wild D. melanogaster is much more complex (Cox and Gilmore, 2007) than that found in laboratory reared flies, comparable to the differences observed between non-westernized human populations and urban populations that consume highly processed diets (De Filippo et al., 2010) (see Box 1). This similarity between flies and humans reveals the importance of host-microbiota homeostasis for human health (David et al., 2014; Kostic et al., 2013). For example, Shin et al. (2011) demonstrated how the Drosophila gut microbiome regulates the metabolic homestasis of the fly.

Global environmental change: detoxification and stress resistance

Environmental change is actually a complex of changes, both abiotic and biotic. Abiotic challenges include changing temperature and humidity, and biotic challenges, often fomented by abiotic shifts, include changes in available habitat, presence of pathogens, parasites, competitors and invaders. Understanding adaptation to global environmental change thus also is a complex problem, and one that requires us to monitor natural populations, as well as to conduct laboratory studies to discover the bases of adaptations or the lack thereof. Natural populations and laboratory strains of D. melanogaster have been successfully exploited in examining responses to changing environments (Rodríguez-Trelles and Rodríguez, 2007; Hoffmann, 2010). The susceptibility of D. melanogaster to global environmental change is well documented in the clinal or seasonal changes in the frequencies of alleles at particular loci (Umina et al., 2005) and in changes in chromosomal inversion frequencies (Anderson et al., 2003). Several thousand Drosophila species, some with highly specialized ecologies, are limited in their distributions to very cold or very hot climates. For example, D. pachea is endemic to the Sonoran Desert of North America, where it depends on the sterols in the cactus Lophocereus schottii, which has alkaloids that other Drosophila species cannot tolerate. Because of its obligate association with its cactus host, it is exposed to temperatures that often approach 50°C. Such species provide unprecedented opportunities to understand the genetic bases of adaptations to extreme situations (see Box 1) and to recruit these species to address problems of species loss in the face of global warming and other anthropogenic changes.

Another product of anthropogenic change is the evolution of pesticide resistance in a wide range of insects of economic and medical importance. Natural and laboratory populations of D. melanogaster have played key roles in our understanding of the roles of the cytochrome P450-encoding genes and the glutathione S-transferases in resistance to the insecticide, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (better known as DDT) (Ffrench-Constant, 2013). Various other Drosophila species have specialized on resources (such as cacti or Morinda fruit) that contain a range of allelochemicals, or secondary metabolites, many of which are toxic to other organisms and thus serve as defense against herbivory. The genetic bases of these specializations, as they relate to phenomena such as the evolution of pesticide resistance (McDonnell et al., 2012; Miyo, 2012) and detoxification (Gloss et al., 2014; Mitchell et al., 2014), are already being investigated through comparative genomics.

Combining genomics and natural history

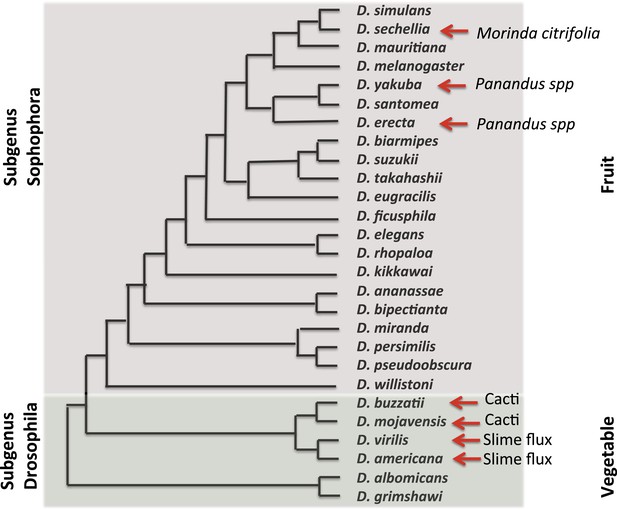

In 2003, the fly community submitted a white paper for the whole-genome sequencing of additional Drosophila species. The resultant 2007 publication by the Drosophila 12 Genomes Consortium et al., 2007, of 12 genomes and their analysis, has rapidly revolutionized and expanded the utility of the Drosophila system for studies ranging from computational biology and embryology, to evolution and human disease. In the short time since these genomes were made available, insights have been gained into the emergence and loss of new pathways, the gain and loss of pathway complexity (Salazar-Jaramillo et al., 2014), and the changes in the regulatory network of complex genomes (Coolon et al., 2014; McManus et al., 2014). At this point in time, over 30 Drosophila genomes have been sequenced, further expanding the importance of and opportunities provided by these flies. These species, their evolutionary relationships and ecological features, are presented in Figure 2.

Evolutionary and ecological relationships of Drosophila species.

Phylogenetic relationships (based on Markow and O'Grady, 2005b) are shown for species with available assembled whole-genome sequences. Within the subgenus Sophophora, D. sechellia has specialized to consume and breed on Morinda fruit and D. erecta has similarly specialized on fruits of various Panandus species, as has D. yakuba although to a lesser degree. Within the subgenus Drosophila, D. buzzatii and D. mojavensis breed in cacti, while D. virilis and D. americana breed in the slime fluxes of deciduous trees. Even among specialists, adult flies may feed more broadly while larvae are more specialized. Arrows indicate substrate specialization by these species. Image credit: Therese Ann Markow.

The natural histories of these species are diverse. Some are highly specialized and live under extreme climatic conditions. Others are adapted to diets high or low in protein or carbohydrates. Their microbiomes differ (Chandler et al., 2011) as does their genomic machinery for dealing with various environmental challenges (Low et al., 2007; McDonnell et al., 2012).

Conclusions

The expanding number of sequenced Drosophila species' genomes offers a tremendous opportunity to learn from the ways in which different species have solved the challenges of living in different niches. But laboratory studies alone, in the absence of an understanding of the natural history, the challenges and lifestyles of these flies, will never allow us to fully exploit what they have to offer. By characterizing the natural history of not just D. melanogaster but also of those other Drosophilids with contrasting ecologies, we will be able to detect and exploit such phenomena as novel resistance mechanisms and novel dietary adaptations and reproductive strategies.

This knowledge can then be employed to advance our understanding of basic biological principles, thus building a more robust toolbox to apply to human problems. For example, the efficacy of anticancer therapeutic agents depends not only on their effects on the tumor but also on the ability of the host to tolerate the toxic effects of the drug. The many ways in which fly species have dealt with detoxification and tolerance could inform and refine drug discovery. It's not difficult, as one might imagine, to study a large number of different Drosophila species in the wild. But it's time to do more of it.

References

-

BookAnimal Behavior: An Evolutionary ApproachSunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc.

-

The making of a pest: the evolution of a fruit-penetrating ovipositor in Drosophila suzukii and related speciesProceedings of the Royal Society: B Biological Sciences 281:20132840.https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.2840

-

Insect olfaction from model systems to disease controlProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA 108:12987–12995.https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1103472108

-

Homophila: human disease gene cognates in DrosophilaNucleic Acids Research 30:149–151.https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/30.1.149

-

Body size variation in insects: a macroecological perspectiveBiological Reviews 85:139–169.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00097.x

-

Tempo and mode of regulatory evolution in DrosophilaGenome Research 24:797–808.https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.163014.113

-

Genetic variation of Drosophila melanogaster natural populationsTrends in Genetics 4:106–111.https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-9525(88)90098-4

-

Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural AfricaProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA 107:14691–14696.https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1005963107

-

Evolution in an ancient detoxification pathway is coupled with a transition to herbivory in the drosophilidaeMolecular Biology and Evolution 31:2441–2456.https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu201

-

Evolution of herbivory in Drosophilidae linked to loss of behaviors, antennal responses, odorant receptors and ancestral dietProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA 112:3026–3031.https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1424656112

-

Courtship and remating in field populations of DrosophilaAnimal Behavior 45:253–262.https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.1993.1031

-

Molecular evolution of Drosophila odorant receptor genesMolecular Biology and Evolution 24:1198–1207.https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msm038

-

The odor coding system of DrosophilaTrends in Genetics 20:453–459.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2004.06.015

-

Physiological climatic limits in Drosophila: patterns and implicationsJournal of Experimental Biology 213:870–880.https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.037630

-

Insights from natural host-Parasite interactions: the Drosophila modelDevelopmental and Comparative Immunology 42:111–123.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dci.2013.06.001

-

Exploring host–microbiota interactions in animal models and humansGenes & Development 27:701–718.https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.212522.112

-

Historical biogeography of the Drosophila melanogaster species subgroupEvolutionary Biology 22:159–225.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-0931-4_4

-

Drosophila as a model for intestinal dysbiosis and chronic inflammatory diseasesDevelopmental and Comparative Immunology 42:102–110.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dci.2013.05.005

-

Gut microbiota–generated metabolites in animal health and diseaseNature Chemical Biology 10:416–424.https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.1535

-

Reproductive behavior of Drosophila melanogaster and D. nigrospiracula in the field and in the laboratoryJournal of Comparative Psychology 102:169–173.https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7036.102.2.169

-

Forced matings in natural populations of DrosophilaAmerican Naturalist 156:100–103.https://doi.org/10.1086/303368

-

‘Cost’ of virginity in wild Drosophila melanogaster femalesEcology and Evolution 1:596–600.https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.54

-

Evolutionary genetics of reproductive behavior in Drosophila: connecting the dotsAnnual Review of Genetics 39:263–291.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.112454

-

Rapid evolution of smell and taste receptor genes during host specialization in Drosophila sechelliaProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA 104:4996–5001.https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0608424104

-

Evolutionary toxicogenomics: diversification of the cyp12d1 and cyp12d3 genes in Drosophila speciesJournal of Molecular Evolution 74:281–296.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00239-012-9506-3

-

Microdifferentiation in a natural population of Drosophila melanogaster to alcohol in the environmentGenetics 77:385–394.

-

Evolution of splicing regulatory networks in DrosophilaGenome Research 24:786–796.https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.161521.113

-

Human disease models in Drosophila melanogaster and the role of the fly in therapeutic drug discoveryPharmacological Reviews 63:411–463.https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.110.003293

-

Drosophila models of cardiac diseaseProgress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science 100:155–210.https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-384878-9.00005-4

-

Evolution of a cellular immune response in Drosophila: a phenotypic and genomic comparative analysisGenome Biology and Evolution 6:273–289.https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evu012

-

Teneral matings in fruit flies: male coercion and female responseAnimal Behaviour 81:595–601.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2010.12.003

Article and author information

Author details

Funding

National Science Foundation (NSF) (DBI-1351502)

- Therese Ann Markow

Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (National Council of Science and Technology, Mexico)

- Therese Ann Markow

University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States (UC MEXUS)

- Therese Ann Markow

The funders supported the gathering of many of the observations reported in this paper.

Publication history

- Received:

- Accepted:

- Version of Record published:

Copyright

© 2015, Markow

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 17,088

- views

-

- 2,542

- downloads

-

- 178

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Ecology

- Evolutionary Biology

Essays on the wild lives of model organisms, from Arabidopsis to the zebrafish.

-

- Ecology

Optimal foraging theory posits that foragers adjust their movements based on prey abundance to optimize food intake. While extensively studied in terrestrial and marine environments, aerial foraging has remained relatively unexplored due to technological limitations. This study, uniquely combining BirdScan-MR1 radar and the Advanced Tracking and Localization of Animals in Real-Life Systems biotelemetry system, investigates the foraging dynamics of Little Swifts (Apus affinis) in response to insect movements over Israel’s Hula Valley. Insect movement traffic rate (MoTR) substantially varied across days, strongly influencing swift movement. On days with high MoTR, swifts exhibited reduced flight distance, increased colony visit rate, and earlier arrivals at the breeding colony, reflecting a dynamic response to prey availability. However, no significant effects were observed in total foraging duration, flight speed, or daily route length. Notably, as insect abundance increased, inter-individual distances decreased. These findings suggest that Little Swifts optimize their foraging behavior in relation to aerial insect abundance, likely influencing reproductive success and population dynamics. The integration of radar technology and biotelemetry systems provides a unique perspective on the interactions between aerial insectivores and their prey, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of optimal foraging strategies in diverse environments.